When one sees a clip from auteurs such as Godard or Bergman, it is difficult to attribute it to the wrong filmmaker, as they have an unmistakable quality. But what of the oeuvre of Robert Bresson? Bresson made only thirteen feature films, but is often cited as a major film influence globally. His works vary greatly in style and subject. Nonetheless, Jean-Luc Godard has said that “Robert Bresson is French cinema, as Dostoevsky is the Russian novel and Mozart is German music.” So what is it then that encapsulates Bresson’s essence?

Well, for starters, most of Bresson’s protagonists are in an immense struggle with their environs, caught in circumstances they can’t easily extricate themselves from. Sometimes these confines are an actual prison, as in his 1956 masterpiece A Man Escaped, which details the jailbreak of a Resistance member out of Nazi-controlled Montluc prison in Lyon.

Although adapted from writings by André Devigny, Bresson himself was held prisoner by the Germans, which had a lifelong impact on his work. Christian themes of redemption and transcendence so primary in A Man Escaped are also imperative. If a character is not actually imprisoned, then it is their class, gender, alienation or a combination of these factors which conspire to immobilize them.

As Bresson said of his character Mouchette – “She is found everywhere: wars, concentration camps, tortures, assassinations.” Mouchette is ostensibly a “free” person, but due to ignorance and callousness members of the community each in their turn become warden, judge, torturer. As a girl born into abject poverty such humiliation is the destiny of Mouchette.

Another defining Bresson quality is sparseness. Every shot is significant and necessary, compositions kept minimal. Dialogue isn’t absent but pared down substantially. The image itself often reveals the complexities of his characters and their transformations. Bresson shows but doesn’t tell. This interiority is underscored by Bresson’s repeated use of the epistolary form.

Letters and journals serve not just as exposition, but emphasize the importance of an inner life to his characters and their desire for communication. And further yet, an absence of non-diegetic sound (i.e. a soundtrack) is yet another minimalist component.

The focus on content is greatly highlighted by a good dose of Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, or distancing effect, evoked by the intentionally wooden performances of Bresson’s actors, who often did not even have acting backgrounds. Distancing is also achieved through repeated visual motifs and unconventional frames. These contrivances remind us that we indeed are in the process of watching a film.

Fans of more eventful storylines undoubtedly might find Bresson to be tedious. But those who give the films the attention they merit can learn much about the potential of moving image as language. Now let’s explore ten films, in no particular order, by filmmakers who have expressed Bresson as an influence, or which are somehow very Bressonian films.

1. Tout va bien (Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, 1972)

The film begins with a male voiceover that says – “I want to make a film.” A female voice replies – “You need money for that.” A director’s hand signs cheques to different types of film workers. “You need a story” continues the female voice. “We need a story?” asks the director. Of course by now we know that there might not be much of one. Or at least, we are being encouraged to examine more closely the content of what we see, as well as what we believe regarding the structure and purpose of cinema.

Next Susan (Jane Fonda), an American reporter, and her husband Jacques (Yves Montand), once a Nouvelle Vague director but who now makes commercials, are shown having a quiet romantic walk together. “Do you love me?” Susan asks. Jacques responds with a list of her body parts, insisting he loves each one. Those who have seen Godard’s Le Mepris (1963) will instantly recognize these declarations as being taken directly from that film.

The device is witty, but also emphasizes as does the introduction that Susan and Jacques are merely, as in Bresson’s cinema, models or mannequins being manoeuvred to convey the film’s content. The female voiceover returns and says the film also requires “Workers who work” and “bourgeois who bourgeois”.

We see workers in tractors beside a giant mound of burning potatoes, this provocative image alluding perhaps to the great amount of food waste in French society (see for example Agnès Varda’s wonderful 2000 documentary The Gleaners and I) but it also suggests how the labourer’s work is severely undervalued.

Susan and Jacques visit a sausage factory, where workers tear up files and engage in other hostile acts. The manager has been locked in his office for hours but they are allowed in to interview him. The camera perspective suddenly cuts to a slow pan of the factory in cross section. This astonishing shift is perhaps one of the most brilliant uses of distancing in the history of cinema.

Bresson too exploits images of grid patterns and grilles to reinforce a state of psychological imprisonment in his characters, particularly in The Ladies of the Bois de Boulogne (1945) and Diary of a Country Priest (1951). Here Godard and Gorin achieve the same effect, but in a different way. Suddenly the characters are in a cage, one which was there before but which was not visible to the viewer. Workers stand in blood-soaked aprons beside drafting tables and wall charts. We sense that perhaps partitions between manager and labourer, bourgeois and proletariat, are flimsy indeed.

While scenes shot outside the factory are in a more muted palette, scenes within are mainly in red, white and blue, colours of the French flag. Anyone familiar with Godard will come to recognize his device of focusing on two or three colors in a scene, often red, yellow, blue, or that “psychological primary” of green with one secondary color for contrast.

This conspicuous use of color seems quite different from Bresson’s ascetic black and white, or the toned-down hues of his color features. But in Godard, (and despite Gorin’s co-direction, in appearance this is a very Godardian film) his use of color is so consistent that it becomes both signature and distancing effect – illustrating how he like Bresson is amongst the purist of filmmakers, creating great works of cinema aesthetically, which at the same time are of the utmost social significance.

2. Light Sleeper (Paul Shrader, 1992)

The film opens with John LeTour (Willem Dafoe) seeking out a client for a drug dropoff late at night at a movie rental place. Afterwards his voiceover complains about how busy he is trying to get people drugs, how demanding they are, and the art of trying to remember their names. He reveals he has started keeping a diary, as did Bresson’s criminal hero in Pickpocket, who Shrader has said the character is somewhat modeled after.

He drops by the apartment of his boss lady Ann (Susan Sarandon), unloading drugs he didn’t sell and a big wad of cash. Ann is vamped out in an orange-red suit which looks business-like except that it is cut at the thighs. Not your typical drug dealer. He returns home and writes at a table in his grungy, sparely-furnished apartment.

The next day while talking to another delivery person we discover that Ann might be quitting the business. The other man asks John what he will do. He doesn’t know but says he’s not “the management type”, and fears he will start using again. Perhaps he will go into the music business. LeTour is clearly a thoughtful man who wants more out of life.

After he reconnects with an old lover Marianne (Dana Delany) and she dies in a mysterious way, John begins a quest for justice, which culminates in a memorable shootout in a hotel room. Our protagonist ends up in prison, writing letters and like Bresson’s Pickpocket hero, has undergone a spiritual transformation. Part traditional noir, part modern thriller, a difficult film to classify, but which is thoughtful, and sometimes, very amusing.

3. The Mother and the Whore (Jean Eustache, 1973)

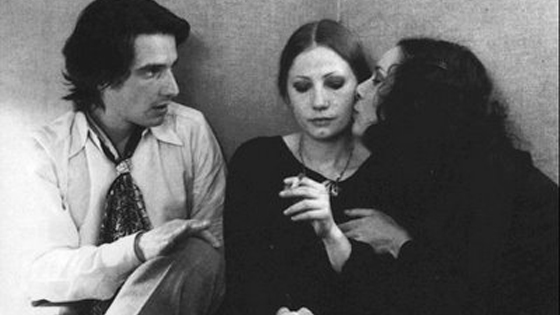

Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Leaud) is an unemployed intellectual. He lives with and is supported by Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who owns a small clothing store. At the film’s beginning, we see Alexandre leaving a sleepingMarie in bed early in the morning. He encounters Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), who he had a relationship with and is intent on pursuing. Alexandre and Gilberte end up at a café and Alexandre persists in his overtures. He is upset that Gilberte lives with another man.

Why won’t she marry him? At this point, we do not know who he was sleeping with in the morning. Was this a one night stand? Alexandre seems desperate, weak, an overly romantic figure. “You are really naïve.” says Gilberte scornfully. Next we find him at Les Deux Magots (the haunt of Jean-Paul Sartre) visiting with a long-haired friend who looks the typical young radical of the era.

Leaving Les Deux Magots Alexandre first spots Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), an anaesthetist (loaning a witty black gloss to the film), sitting on the café terrace. Lebrun was not a professional actress when she was cast, but a student who had broken off a relationship with Eustache.

We discover that Marie voices consent to Alexandre’s seeing other women, while her body language and outbursts say otherwise. The Mother and the Whore examines Alexandre’s relationships with these women in detail. Its agonizing pace and flatness of vision are obviously influenced by the fiction of Jean-Paul Sartre, who at one point supposedly appears in Les Deux Magots, his back to the camera.

Of course Alexandre qualifies as a Bressonian-type character simply because of his outsider status, poverty, cramped living quarters and failure at life. He seems to have a constant supply of women and friends who listen to him, yet we notice how often he refers to his alienation. No one has ever been as alone, and in such an interesting way as he. If at the film’s beginning we find him to be foolish, as things progress his character darkens.

Facing the camera, he speaks of his past relationship with a woman, who we assume to be Gilberte, who he beat into a state of unrecognizability. Here Leaud, stone-faced as many of the best Nouvelle Vague actors, and any of Bresson’s main actors, gives a disconcerting, expressionless performance. Alexandre starts ranting about this woman not wanting him, then begins complaining about major political upheavals as though they were a conspiracy against him.

Suddenly, an Alexandre is revealed possessed of a horrifying misogyny and egoism. Then how soon this is forgotten, as the film reverts to its painful banalities. There has perhaps been no other film where a stylish veneer is so incredibly at odds with what lies beneath its surface. And what lies beneath the veneer of The Mother and the Whore is absolute brutality.

If one watches this film after Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971) the character of Gilberte is immediately recognizable as being the same actress, Isabelle Weingarten, who played the role of Marthe in Bresson’s film. In Bresson, Marthe is about to commit suicide but is saved by Jacques, an unrealistic youth who dwells in imaginary romantic fantasies, and who, as you might have guessed, bears a striking resemblance to Jean-Pierre Leaud’s character.

In The Mother and the Whore the doubling doesn’t stop there. The character of Veronika is a double to Gilberte, and if Gilberte resembles her role in Four Nights of a Dreamer, then Veronika is wearing the same clothes exactly, from her gothic “Moroccan shawl” to the tips of her black granny boots. At one point Alexandre is at a friend’s apartment, listening to a singer who the friend says is an imitator, but “better than the original”.

Diegetic music is of the utmost importance in this film, acting as a ventriloquism for feelings the characters cannot express, or perhaps, an inner life they don’t have access to. The friend introduces Alexandre to a game of staring at a frog’s image, only to see afterwards its mirage adrift on the ceiling.

This is what Eustache has done with Bresson’s characters. They are the same, but they are also negative images. They are like fruit which has been left out and rotted. And as Four Nights of a Dreamer is not Bresson’s greatest work, it probably is an example of the imitator outdoing the master.

4. The Match Factory Girl (Aki Kaurismäki, 1990)

Iris (Kati Outinen) is a young Finnish woman leading a lonely existence. The film opens with a beautifully prolonged sequence showing machinery operating in a match factory, which is not only visually interesting, but gives us an idea of the repetitive nature of Iris’ work and existence.

One afternoon Iris gets paid and walking by a shop admires a dress in the window. She comes home with the dress and gives the rest of her pay to her mother. Her mother, a morose-looking woman, is upset and her mother’s partner slaps her and calls her a whore. Her mother tells her to return the dress.

Instead she goes to a public shower, dresses up and goes to a bar. She looks prettier and happier having her beer. She meets a man, Aarne, she seems to have an instant connection with. He grabs her hand and leads her to the dance floor for a slow dance.

Iris spends the night with Aarne and we see that his apartment is stylish and nicely furnished. If he looked a bit grungy and working class in the bar, now that it is morning he is in a suit. With a kind of condescending smirk, he leaves a 1000 markka note on the bedside table where Iris is sleeping. When she wakes up she leaves a note asking Aarne to call her.

Aarne isn’t interested in Iris but finally one night he agrees to a date. Iris is shown getting ready with her mother, and they both look much more cheerful. They go to dinner and if at the film’s beginning Iris looked defeated and plain, she is smiling and looking more attractive than ever. He asks her how her food is and then tells her that there is nothing lasting between them. “Nothing could touch me less than your affection” he says, just to make it clear. He tells her to leave, snorting with contempt and amusement after she is gone.

Iris turns out to be pregnant and everyone she encounters treats her with cruelty. She plots a revenge at once ghastly, comic and fascinating. Kaurismäki has cited Bresson as a major influence and it is not difficult to see here. Iris in her constant struggles and humiliation is very much the Bressonian female. His work in its sordid depiction of reality is also reminiscent of Fassbinder or some of the best of British New Wave cinema.

5. The Nun (Jacques Rivette, 1966)

Adapted from Denis Diderot’s 18th century novel, the story follows the sufferings of Suzanne (Anna Karina), who at the beginning is shown with nuns in a wedding dress behind bars, separating her from spectators in society dress of the era. When asked if she will promise God chastity, poverty and obedience, she refuses. We learn that her mother’s husband is not her real father and her mother no longer wishes to be reminded of her sin. The family is running out of money and sending her to a convent is less worrisome than trying to find Suzanne a husband.

Forced into convent life, the mother superior encourages Suzanne and she becomes her favourite. She prays for strength and although she does not want to be a nun, seems to be a person of faith. She takes her vows and is no longer a novice.

Suzanne’s mother dies, as well as the mother superior. The new superior, Sister Sainte-Christine, punishes Suzanne for burning her hair shirt. What follows is a portrait of community ostracism and hysteria. Suzanne becomes dead to the community and must beg for scraps. She is humiliated, bound and half-starved.

Suzanne manages to contact a lawyer, Mr. Manouri, who she hopes can free her from her vows. This only further aggravates Sister Sainte-Christine, who becomes convinced that Suzanne is possessed and in need of an exorcism. Although she loses her case, Manouri arranges her transfer to another convent, where we are struck by signs of luxury and comfort. The mother superior, Madame de Chelles, does not even wear a habit much of the time.

If the last mother superior was hateful, Madame de Chelles seems quite the opposite. Eventually it becomes clear that Madame de Chelles has a lesbian obsession with Suzanne, even crying outside her room at night, although Suzanne herself does not reciprocate. She eventually runs away with a monk, who forces himself on her. Then she is shown carrying heavy buckets on a milkmaid’s yoke and working with laundresses.

This story and Karina’s impassive performance are entirely Bressonian. The film in its severe compositions and exploitations of grilles has many similarities visually with Diary of a Country Priest, and her end is as tragic yet cathartic as that of Mouchette.

The film could easily have become pure nunsploitation, but if you have read Diderot’s novel if anything Rivette has toned down the eroticism, maintaining the seriousness and integrity of his subject. The Nun not only addresses timeless issues regarding women, but also illustrates so well how profound a gap there can be between faith and its institutions.