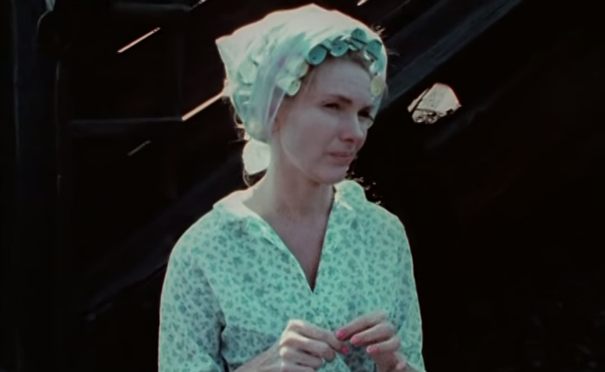

5. Wanda (Barbara Loden, 1970)

By the time Barbara Loden was underway with what would be her only cinematic outing as director, she was already a Tony Award winning actress as well as a long-time member of the Actors Studio and the wife of acclaimed director Elia Kazan.

The film played at the 31st Venice International Film Festival where it won the Pasinetti Award for Best Foreign Film. It is set in the anthracite coal region of eastern Pennsylvania, telling the story of an unhappy housewife who leaves her husband only to fall into an abusive relationship with an aging hood and then proceed to go on a crime spree together.

Wanda is frequently bleak and brutal. Though it draws paralells with other crime films of the era such as Bonnie and Clyde or Badlands, neither of those are as unsympathetic as Wanda. It is so resolutely indifferent in its portrayal and treatment of its titular character that it is regularly unnerving and disturbing.

It features a woman who is so lacking in self-esteem that it draws empowering themes only by emphasising how one sided and hopeless the war between the sexes is for some people. The character of Wanda is essentially a mediocrity who is continuously suppressed and abused by the system around her, almost powerless against the men that dominate her life. The film is also improvisational in style and meditative in nature, similar to the works of European directors like Robert Bresson.

Despite the critical acclaim Wanda received, Loden struggled to find another directing job in a relatively harsh cinematic landscape.

At the time of her death from breast cancer in 1980, Loden was still trying to realize her directorial ambitions and continue the themes raised in Wanda with an adaptation of Kate Chopin’s proto-feminist novel, The Awakening, but the project never came to be. However, the legacy of Wanda, one of the very few American feature films directed by a woman at that time, endures.

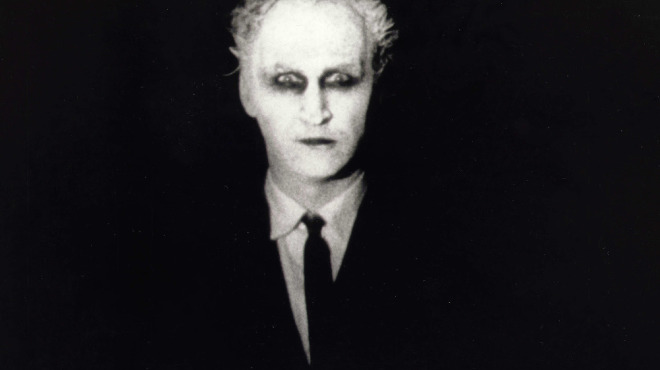

4. Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

This 1962 independent horror film failed to gain notable attention upon its initial release as a double feature with The Devil’s Messenger. Today, however, it is regarded as a cult classic and cited as a key influence on the works of David Lynch and George A Romero. The plot follows a young woman whose life is disturbed following a car accident but also finds herself drawn to a mysterious the pavilion of an abandoned carnival.

Its director, Herk Harvey was said to have directed over 400 films over the course of his career but nearly all of them were educational and industrial training films which he shot for the Centron Corporation. He then put his experience of working with a low budget to good use as he crafted a low budget horror film that relied more on a slow build of tension and created an uneasy atmosphere in order to induce fear from the viewer.

The crisp and high contrast black and white photography and frequently disturbing visuals result in a surprisingly effective low budget horror movie, and the cast are able to perform their roles with enough conviction to immerse the viewer within the eerie and twisted world, a rarity for a horror film of that era, let alone one with a budget as low as Carnival of Souls.

But like many movies of its kind, Carnival of Souls was overlooked and underappreciated at the time of its release. The film was such a commercial failure that the distributor went bankrupt, leaving Harvey with no option other than to return to his job of directing educational and industrial training films. It’s a great loss for the genre, as one can only imagine what Harvey might have been able to craft with a bigger budget, a filmmaker of his talents was wasted making short educational films.

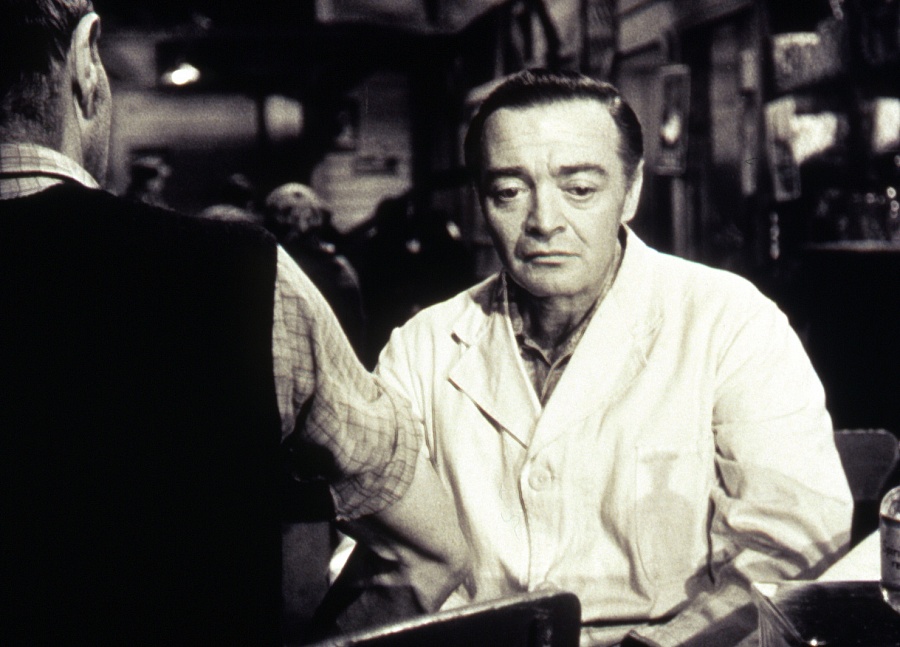

3. Der Verlorene (Peter Lorre, 1951)

Though he is widely recognised for his terrific performances, having got his big break at the age of 26 in Fritz Lang’s 1931 masterpiece M, Peter Lorre was able to craft one superb noir feature as a director and writer. During his twenty years between M and Der Vorlorene, Lorre gained significant knowledge of the international film circuit and applied this accumulated knowledge to write and direct his one and only feature film.

Lorre starred in the lead role as a man who gets away with murder under the Third Reich and then in the years after World War 2 reinvents himself as a doctor. It is an art film in the film noir style and was clearly a comment on the oppressive regime that forced Lorre into exile. In front of the camera, Lorre gives a chillingly subtle performance, having redefined the psychopath role in M he takes a similar approach here with terrific results.

The plot unfolds almost entirely in flashbacks that provide a haunting exploration of his psychological weaknesses. Through the doctor’s story we get a portrait of an entity haunted by its past, knowing that there is blood on its hands and all it can do is try to move on with the present.

It is of course a painfully relevant allegory for Germany itself at the time of the film’s release. Even more remarkably though is how Lorre uses the horrors of the past to draw a parallel with the present, noting that despite the brutality of the past its audience is living in what could be an even bleaker present.

2. Johnny Got his Gun (Dalton Trumbo, 1971)

A harrowing and brutal anti-war drama that stands as the only directorial feature by acclaimed screenwriter Dalton Trumbo. Trumbo was one of many writers who was blacklisted for refusing to comply with House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 during the committee’s investigation of Communist influences in the motion picture industry.

Though he continued to write many scripts under pseudonyms, his adaptation of his own novel of the same name was an aggressive and confrontational film that spoke on a directly human level to make it deeply disturbing and horrifying.

It tells the story of a soldier in World War I by the name of Joe Bonham, who is sent on a patrol into no man’s land when a shell lands near him. He wakes up in a hospital, where he soon learns that he has lost his arms and legs as well as most of his face, robbing him of the ability to see, hear or speak, turning him into a prisoner within his own body.

Unaware that, Joe still possesses a conscious mind, the army decides to keep him alive to study and learn from him as Joe desperately tries to communicate with the outside world.

That premise may sound devastatingly bleak and the film itself is even more so. It was one of the first major films to be so outspoken, brutal and unflinching in its criticism of war and its depiction of the effects war has on the human psyche. It does this to such a terrifying and horrendous extent that Johnny Got his Gun is less of a war film than it is a horror movie.

Through flashbacks and surreal fantasies that all take place within Joes’ mind, Trumbo’s film paints a harrowing portrait of an individual sentenced to a form of living death, With its high contrast of the surrealism taking place within Joe’s mind and the horrifically bleak world around him, Trumbo has to be credited with balancing these elements to create a traumatic and poignant film.

Having been released in 1971, the film was also heavily political. The parallels to the ongoing Vietnam War were obvious, with the scarred soldier being unable to communicate with the outside world, silenced by the system around him. Despite the fact that he continued to write screenplays, Trumbo’s failing health prevented him from directing another feature film and he died just five years later in 1976.

1. The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

Could it ever be anything else? Undoubtedly the universal flagship of directors that only made one film, Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is one of the greatest American films ever made. It’s a dark fairy tale, a visual nightmare and an expressionistic idiosyncrasy. The plot focuses on a corrupt reverend-turned-serial killer who attempts to charm an unsuspecting widow and steal $10,000 hidden by her executed husband.

It is a compelling, frightening and visually stunning film that was such a radical departure from anything else being made in Hollywood at the time. Laughton’s bold visual style evoked a sense of eeriness that few films have captured as well since. Laughton’s use of bizarre shadows, stylized dialogue, distorted perspectives, surrealistic sets and odd camera angles helped to create this sinister mood and atmosphere that permeated the film.

At the time, it was considered a commercial and critical failure, that many assumed would always be overshadowed by Laughton’s acting career. To the contrary though, over time the film has grown considerably in recognition and has been proven to have a lasting and enduring impact.

By setting his story outside any sense of conventional realism, Laughton was able to inject a sense of timelessness to it. As opposed to looking strictly artificial his expressionistic and minimalistic set pieces, the directorial flair creates a stranger and more vivid realm.

One of the most memorable aspects of the film is Robert Mitchum as the despicable ‘Reverend’ Harry Powell. He is one of the most unforgettable and iconic villains in cinema history, truly frightening yet also utterly magnetic. His entire demeanour in the film gives the impression of a conman, a crook with just enough wit and charm to navigate through the average townsfolk but Mitchum easily snaps into the menacing and frightening murderer that continues to be referenced to this day.

Laughton’s film proved to be too much for the moviegoers of 1955 and as a result of its commercial failure he struggled to gain support for any further projects. Even more tragic was the fact that he died just seven years later while the film was still very much regarded as a failure.

As a result, we lost an opportunity to see a true visionary undertake other projects, the chance to see just one more film with Laughton behind the camera is tantalising one, but one that will sadly never come to fruition. However his first and only masterpiece still stands as a magnificent legacy, proving that some filmmakers can accomplish more with one film than other do in their entire career.

Author Bio: Joshua Price considers himself more of a fan that happens to write near insane ramblings on movies and directors like Scorsese, Spielberg, Bergman, Kubrick and Lumet rather than an actual critic and other insane ramblings can be found criticalfilmsuk.blogspot.co.uk.