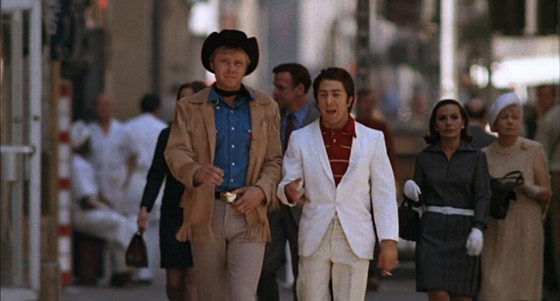

6. Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Director John Schlesinger’s film based on the novel of the same name by James Leo Herlihy sees a naive Texan, Joe Buck (Jon Voight) head to New York with the aim of becoming a male prostitute for wealthy women. Having little success, he encounters ‘Ratso’ Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman) a conman who (despite the friendship which eventually forms) quickly deceives Joe out of $20 and sends him to the apartment of an eccentric religious fanatic and not the source of the stud work Joe expects.

It is at this moment the audience experiences a series of brief flashbacks to Joe’s childhood, these appear to be a traumatic baptism. From this point Waldo Salt’s script launches into a montage which combines emotive and disturbing flashbacks of Joe’s more recent past (there appears to be a sexual assault of whom we are to assume is his former girlfriend and possibly himself) with his frantic searching the streets for Ratso.

This search takes a nightmarish quality as Ratso evades Joe, almost appearing and disappearing. The montage also features further anti-realist moments with Joe’s hands throttling Ratso.

This use of montage, a sequence which barely lasts a few moments in screen time, provides the audience with information of Joe’s mental state (perhaps leaving them as disturbed as he is at that point), his back story and does moves time forward (a fairly stock function). For the screenwriter the lesson here is that can take only very brief visual images to convey a great deal of information and mood to an audience.

For the first time viewer there is the chance that some of these images are in fact flash forwards – heightening suspense. Joe is still very much a lone protagonist at this point, the montage serves to break this barrier and grant the audience some sort of insight into his psyche.

This should serve as a reminder of the power images within montage, and indeed the flash cut, in teasing out exposition, creating suspense and heightening pace and tension. Montage does not always have to be a clichéd tool to fall back on for a ‘getting the plan together’ sequence.

7. Ferris Buller’s Day Off (1986)

‘Life moves pretty fast, if you don’t stop and take a look around in a while you could miss it.’ So Ferris Buller (Mathew Broderick) tells us in the opening to writer and director John Hughes’ comedy. One can quickly identify this as the theme/premise central to the film. There is little room here to begin explaining story structure and theory but the film offers up a good example of structure, pace and theme throughout. The art gallery sequence in particular presents evidence toward this.

Here the otherwise frantic nature of the film slows into a musical montage (Dream Academy’s instrumental version of the Smiths’ ‘Please, Please, Please let me get what I want’) as Ferris, Sloan (Mia Sara) and Cameron (Alan Ruck) drift around the gallery. The montage is broken into a series of fleeting moments, almost stills, moments which would otherwise be missed if ‘we hadn’t stopped to look around’ – thus conveying the central theme of the film.

Importantly for the screenwriter, this sequence occurs almost exactly at the mid-point of the film, a pivotal moment upon which ‘Hero with a Thousand Faces’ author Joseph Campbell would likely place the ‘innermost cave’ sequence where a hero must face their ‘greatest fears’ – in this instance the realisation that one could easily miss out on life and its many precious moments.

This centre point represents the ideal opportunity for the screenwriter to interject the more thematic and symbolic. This is something signified most strongly as Cameron stares (the shot cutting closer and closer) into a painting (Georges-Pierre Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte) until the audience like him observe/appreciate the tiny dots of the paint and the canvas which make up the complete picture – precious details so easy to miss.

This centre point of the script also allows for a broader more mature, perhaps even reflective, tonal depth to the film. Pace wise it allows the audience a breath, time to think (another example of a quiet moment) and digest the film’s theme before a sharp cut away and upping of tempo to the next sequence (the fast and loud float sequence). Granted this scene was ‘shuffled’ slightly in the editing process but the fact that it sits central in the finished film argues its value further.

It should be noted here that it is Cameron who faces the brunt of the ‘fear’– for (arguably) he is the true protagonist of the film, the one who undergoes change, unlike Ferris. In this instance the film as a whole offers up an example of how a writer may deal with the issue of a ‘passive protagonist’.

8. KES (1969)

Ken Loach’s film of the novel (A Kestral for a Knave) by Barry Hines offers the screenwriter a simple but clear message for putting the sense of loss across to an audience. The instructions are clear (and blunt) –give it and then take it away. The ‘escape’ young Billy Casper experiences as he trains his hawk Kes launch the audience on an emotional journey with him, sharing those moments of screen time.

This makes the final scene of the film where he buries the bird (killed by his own brother) beneath a hedge, digging a crude grave with an axe head particularly stark. In the end the audience are left with a feeling of complete loss, an emptiness the seemingly abrupt ending leaves them to deal with alone. The fairy tale is over – back to harsh reality.

9. There’s Something About Mary (1997)

If comedy is to be placed under three separate headings of: The Grotesque, The Unspeakable Truth and Embarrassment – There’s Something About Mary’s (directed and co-scripted by the Farrelly brothers along with Ed Decter and John J Strauss) prom night sequence in which nerdy Ted calls around to collect his date, Mary from her family home, takes a quick ‘bathroom break’ and ends up with a certain part of his anatomy caught in his zipper has much to offer the screenwriter by way of example.

Ted stands in his prom suit and begins to urinate, he is totally relaxed almost drifting into daydream about what may lie ahead; we hear the melodic sound of the Carpenters as his eyes catch sight of two doves just outside the window.

What could possibly go wrong, the audience are almost as relaxed as Ted perhaps feeling an empathy with him, but already they anticipate something more, something comedic. Suddenly he notices his date Mary, through a window opposite the bathroom, her mother hurriedly dressing her. Ted quickly looks away but not before they notice him looking – in the confusion he rushes to pull up his zipper and the inevitable happens.

In the first instance, the above, and the whole sequence which follows could be viewed as a simple one-trick physical slapstick gag, an example of the ‘grotesque’. However, there is much more going on here – the audience have already shared an example of embarrassment (the least appropriate thing to happen at that time) with Ted as he witnessed Mary changing only to be followed by an even more inappropriate zip incident – a double punch line. Importantly for this example, the sequence does not stop there and cleverly escalates, continually combining the three comedic approaches to maximise the humour potential.

The events which follow push the audience ever onward, leaving them only to consider how far will it go and where will it end as the embarrassment gags advance onward.

Firstly, Mary’s family assemble outside the bathroom, her father, her mother and her brother. Mary’s mother is convinced Ted was masturbating, something that she whispers, an ‘unspeakable truth’ (something which cannot and must not be said/revealed) released/turned into a comedy catchphrase by Mary’s younger brother who chooses to continually bellow it at the least appropriate moment, usually the most public, for added embarrassment.

Mary’s rather unsympathetic father enters the bathroom to free Ted from his zipper, again embarrassment we share with Ted. Mary’s father initially recoils at what he sees, this retriggers audience anticipation, surely a grotesque moment looms for them when they get to see ‘it’ – the incident itself very much an unspeakable truth in that it is so grotesque.

The sequence becomes more and more public, maximising embarrassment as Mary’s mother enters, then a police officer and a fireman – the more official and more ‘hyper male’ these figures the more embarrassing. A key point for the screenwriter to remember here is that all the emotional embarrassment the audience experience with Ted equates to the physical pain he would surely be feeling – something the grotesque flashcut of ‘it’ eventually allows them to see.

To drive this public embarrassment further, by the time Ted is stretchered from the house, the entire street (including his friends) and a mass of emergency service and news crew vehicles have assembled. The final indignity for Ted being that the ambulance crew drop him just has he is rushed away – leaving the audience to finally relax from the rapid escalation of events and, importantly, well crafted combination of these multiple comedy headings – one feeding into another to keep the sequence going.

10. Frenzy (1972)

The final film in this list is considered by many to be Hitchcock’s last good film. The story, scripted by Anthony Shaffer and based on a novel by Arthur La Bern, focuses on the hunting of a serial killer dubbed the ‘neck tie killer’ (so named as he leaves the tie on his victims’ bodies) strangling women in contemporary (early 70’s) London.

The wrong man, Richard Blaney (Jon Finch), circumstantial evidence built around him soon becomes the subject of enquires and later arrest whilst the audience are soon aware that the real killer is Blaney’s friend Robert Rusk (Barry Foster). There are two important factors for the screenwriter to note in this example, the first being knowing when to end your story.

In the film’s final scenes, Blaney, wrongly sentenced and aware that Rusk is the true killer, escapes custody and makes his way back to Rusk’s flat, to carry out revenge and/or seek justice. Arriving there he enters not finding Rusk but the body of another victim. A beat later, Chief Inspector Oxford (himself having experienced second thoughts as to the true killer’s identity) arrives on the scene. There is barely time for Blaney to protest his innocence before Rusk returns to the flat, without his tie, leaving Oxford to deliver the final line of the film ‘Mr. Rusk, you’re not wearing your tie’.

The film ends at this point, the true killer exposed – no more is needed – the story is told. This is a thriller, relying on audience anticipation and suspense. To finish with a closing scene or two would seem supplementary and allow the audience to calm. Hence an awareness of genre carries an important function for the writer.

Furthermore, additional scenes would likely prove tricky and cumbersome – Blaney’s escape, his future, Rusk’s sentence and Oxford explaining ‘how he knew XYZ…’ would all leave an audience feeling the film dragged that bit too long. A screenwriter must understand the requirements of a ‘genre film’ and importantly know/understand their story fully to identify when exactly it ends.

The second issue here is appreciating just how little exposition may be needed to get a story moving. Hitchcock often spoke of the MacGuffin – an unexplained plot device which motivates a character toward a ‘goal’. Here the reasons for Rusk’s killings are unclear, his motivations for being the ‘neck-tie killer’ are ultimately unexplained – they are a MacGuffin. The audience do not need this explanation as the plot is kept simple with a clear direction, its focus on the race to prevent the wrong man being jailed and the true killer exposed.

Exploring Rusk’s motives and his back story would stifle the film’s pace, perhaps worse still confuse the direction by generating some empathy for the character (Michael Cain apparently turned down the role on the grounds he thought character disgusting). There is also the danger, not in this case, that a plot device can be too much of a MacGuffin, denting the credibility of an otherwise good script/film as the audience too readily ask ‘why’.

These examples like those explored earlier in the list offer the writer some food for thought but also indicate that whatever the ‘rules’ of screenwriting may be and whatever knowledge gained, the process is not an exact science. No one method will work for every script as style, genre, intended audience (the ever changing market) and countless other factors all have their influence.

Author Bio: George Cromack is a tutor at the University of Hull and also Coventry University’s Scarborough Campuses; with a BA in Scriptwriting he also teaches evening classes in Creative Writing, Scriptwriting and Film Studies for the WEA. Working towards his PhD focusing on Folk Horror, he is a keen writer of both prose and script, Cold Calling, a film short written by George premiered in October 2013. Follow him on Twitter @MadBasil.