Postmodernism is a movement that has permeated many forms of art as well as many facets of people’s lives today but its impact on the documentary genre of film is particularly profound and often over looked.

In film, postmodernism is too often assumed the preserve of fiction films. This is because fiction films have fewer problems with postmodernism. Fiction films are allowed to be subjective and disingenuous, whereas documentaries are supposed to be a pursuit of objective truth.

Despite this conflict, postmodernism’s influence on documentary film has become apparent in recent years and this list looks at some of the films that best represent this influence. These films should be of interest to anybody studying or who just has an interest in postmodern theory.

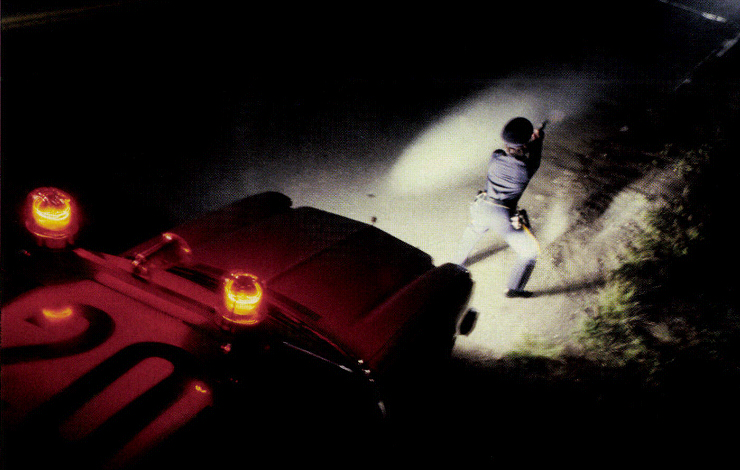

1. The Thin Blue Line (1988, Errol Morris)

Regarded by many as the first postmodern documentary (although some might argue that Claude Lanzman’s Shoah deserves that distinction), it would be unjust if Errol Morris’ film about Randall Dale Adams, a drifter wrongly accused of murder, was not on the list.

The Thin Blue Line achieves the recognition of being the first postmodern documentary because Morris creates an ironic detachment from events in his presentation of the documentary’s re-enactment scenes and in this way the film can be seen as a departure from the typical documentary in which the goal is to achieve an objective truth.

Throughout the film, Morris also intercuts the interviews involving the film’s subjects with seemingly unconnected visuals that invite the audience to further develop a connection and meaning.

It is perhaps ironic that the first documentary that foregoes this desire for objective truth also boasts being the first documentary responsible for getting a wrongly accused man released from prison as Randall Dale Adams was released from prison shortly after the film’s release.

Often revered as the standard bearer in the documentary film genre the film can also be seen to have had a huge influence on postmodern documentaries that came after it, most notably, Netflix’s series, Making a Murderer.

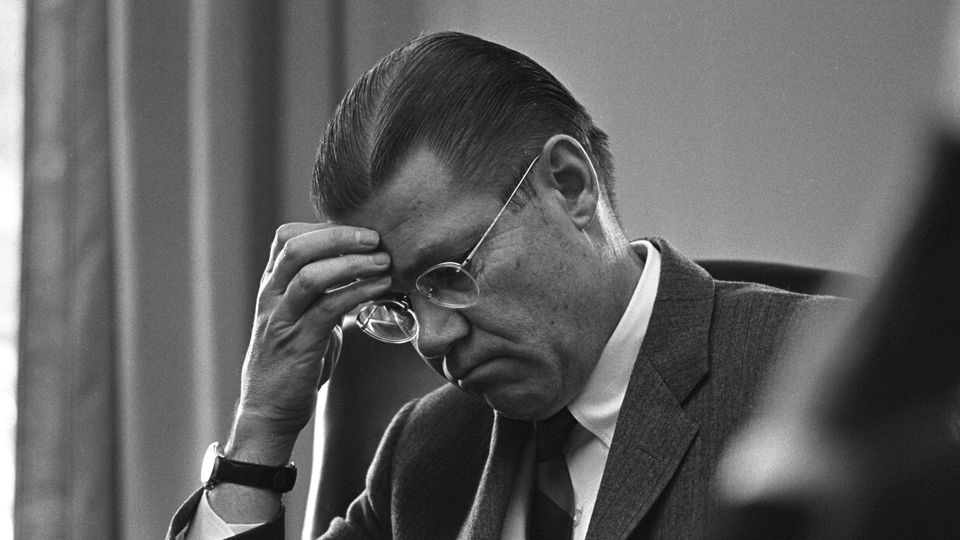

2. Fog of War : Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003, Errol Morris)

Fog of War, to give the film its shorter title, is the second film directed by Errol Morris to make the list and is an Academy Award winning documentary about the life of former US Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. The film also serves the purpose of analysing the moral difficulties of making decisions at a time of war.

In the film, an aged Robert McNamara attempts to come to grips with his role in the decision to go to war in Vietnam whilst also wrestling with some issues that could be considered postmodern in nature.

One example of this is when he reveals lesson number seven to be, “believing and seeing are both often wrong”. A parallel is drawn here with postmodernism’s inability to distinguish between what is real and what is artificial.

As is the case with the director’s earlier film, Morris’ typically subjective approach to storytelling is apparent as McNamara’s interviews are often intercut with seemingly unconnected visuals and archive film that invite the audience to further develop a connection and meaning.

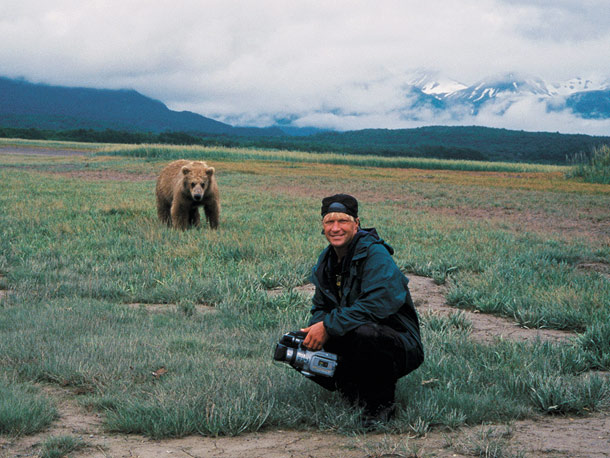

3. Grizzly Man (2005, Werner Herzog)

Grizzly Man chronicles the life and death of Timothy Treadwell. A bear enthusiast who spent 13 summers living in close proximity to wild grizzly bears in Alaska, documenting and videoing his encounters with them before he and his girlfriend are eventually killed by one of the bears he had sworn to protect.

The film is then made in retrospect by acclaimed director, Werner Herzog using found footage filmed by Treadwell along with interviews of people who knew Timothy as well as experts in the behavior of bears.

The film is similar to the other documentaries on the list as Herzog can be seen to favor subjectivity over objectivity in his telling of the story. This is evident in the choices Herzog makes such as his decision to shoot the more unusual subjects of the documentary with a wide-angle lens that exaggerates the subject’s eccentricity.

The footage that Herzog uses of Treadwell from the 100-hour catalogue can also be considered a choice by the director to present his subject to the audience as eccentric, detached from reality and is suggestive of having a spiritual connection with the animals.

In fact, most of Grizzly Man, one can imagine being edited out by a more traditional documentary maker for fear of creating an ironic detachment from Treadwell’s eventual death.

4. Waltz with Bashir (2008, Ari Fohman)

Waltz with Bashir is an Israeli animated war documentary that tells the story of the director, Ari Fohman’s search for his lost memories of his time as a nineteen year old fighting for the IDF in the 1982 Lebanese war.

The film, perhaps more so than any other documentary, shows the postmodern function of animated documentary and this is partly why it has received so much critical success.

The animated form that the documentary adopts allows for a playful treatment of material and a use of parody and pastiche that would not be as effective without the use of animation.

This is because with cartooning also comes a process of amplification through simplification, which essentially allows the artist to strip the image down to its essential meaning and to amplify this meaning.

This is essential for a film of this type that deals with war and trauma as in order to portray the story with any element of subjectivity the story needs to be told in a way that suggests the reality of war without depicting it.

A self-referential moment in the film suggests exactly this when Fohman is told, “It’s fine as long as you draw but don’t film”. This is a must watch, for any fans of the small, but growing genre of animated documentary.

5. Catfish (2010, Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman)

Catfish is a documentary about Nev Schulman and his romantic relationship with a woman that he knows only through Facebook.

The film was highly acclaimed when it came out in 2010 and despite the subsequent MTV series of the same name tarnishing the film’s reputation significantly, it is worth remembering that this is a fine documentary that comments on how technological advancement is responsible for the postmodern world of today.

The film can also be considered a commentary on how identity is no longer fixed but has become a fluid concept and how the postmodern world is unable to distinguish between what is real and what is artificial.

The film’s validity has been challenged since its release with much being written about the manipulation of events in the film. But questions over its authenticity and whether it is a documentary or a work of fiction, in the postmodern age, is no longer the criticism it may once have been.