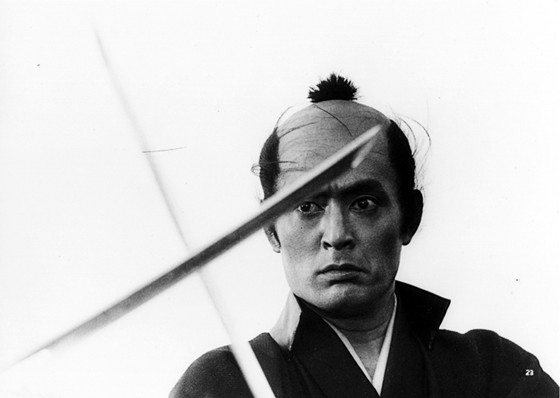

6. Musashi Miyamoto series (1961-71, Tomu Uchida)

Musashi Miyamoto movies are ironically the least popular samurai movies today, though they’re among the best ever made. The series that stick around are the 47 Samurai treatments and Sword of Doom. That second tier of digging gets you to Inagaki’s top tier three part Musashi series, and it’s the third tier that gets you to Uchida’s five part series, which is even better.

It’s no surprise that the most famous adaptation of Japan’s Superman would treat him as such, but it is a little unfortunate that the man doesn’t get his fair shake as a human.

As great a director as Inagaki is, if there is any fault in his version of Musashi, it’s that the man was elevated to deity status. He the perfect warrior; his biggest flaw being his meticulous attention to perfection. Whether or not that is an accurate depiction of the man, it risks detaching the audience from him. Uchida does away with all that. Musashi kills a child. He has regrets. He is, by no means, a perfect person. Musashi is a dirty, interesting, character.

Through the course of the ten hours of movie, the audience gets to know his hot temper, the trouble it gets him in, his crucifixion and rebirth, rise to greatness, the trouble his past gets him in, and his rejection of the society he’s been at odds with the whole time. This isn’t Jesus Christ, it’s Jesus of Nazareth. Inagaki did some amazing camerawork in Chushingura, a moving empathetic camera sadly lost in his Musashi series. Uchida gladly takes up the offer, swooping in, panning back, making it active and involved, less formal, more muddy. Everything matches, even the ugly bits.

Also, a note on the way Uchida stages action. This may be the only time the one-against-a-million schtick works. Kurosawa laid the foundation in Seven Samurai, and Uchida took the reins and drove it to a whole new level. There is a battle in which Musashi is to be ambushed in the middle of a rice field. So, he camps out in the mountains to watch the enemy forces gather in the middle of the night. He draws a map of the layout.

He counts the men, and draws them at their post. He talks to himself about where he needs to attack first, where he needs to move toward, how many men he can handle at once, how many is too many, at what point will he be getting tired and what could he use to his advantage at that point. He figures all the ins and outs, taking his time as the enemy grows impatient.

In spectacular fashion, he executes his plan almost perfectly. “Perfectly,” because he comes out alive and victorious. “Almost,” because he makes mistakes. He accidentally kills a kid who wasn’t supposed to be there. But Uchida figured out the key to it all. If you want to hold an audience’s interest, then with great improbability comes great explanation.

7. 47 Samurai (1962, Hiroshi Inagaki)

Ah, what a feast. Inagaki does everything right. Where Mizoguchi’s version begins with Asano’s downfall and punishment, Inagaki understands that it’s all meaningless if the audience doesn’t care about the mission to begin with. Should they just trust that the ronin are doing what they do for a worthy cause? Or should they fall in love with Asano, only to have him ripped from their hearts, and now seek revenge on Kira? Right out of the gate, Inagaki makes this a very personal story.

The first characters introduced are a happily married couple in their fifties, completely comfortable in each other’s presence. The camera is interested in them, and moves to get to know them better. The audience then sees Kira, the lustful, greedy scumbag, in still shots looking at him in disgust; still, and from a distance. Politely composed, and boring.

This jidaigeki is less about the slashing, and more about why people even bother to do it in the first place. The famous story itself is about a group of people who wait a decade to even have a showdown. It’s about that kind husband and wife team. The audience is set up to love them, so that they’re crushed when the couple has to divorce, in respectful silence, because of the secret the husband keeps from even her. It’s about his son, whose only mission in life is to do the right thing, and struggles as a late teen to express himself the right way.

It’s about the samurai who die under that husband’s watch, and how he splashes water on his face and laughs off the tears at a party, so no one becomes wise. He can’t even mourn. He can’t tell Asano’s, his dead master’s, wife. She thinks he’s an embarrassment for buckling to the shogunate, because she simply can’t know.

These 47 samurai have to betray their fiancees’ trust, lie to the ones that matter most, give up every nickel they have, for the sole purpose of essentially attacking their society. All in the name of doing what’s right, according to their sense of honor. Perhaps they succeed.

But once the mission is over, all 47 were forced to commit harakiri. After all, it was an offense to society to break the rules.

8. Sword of the Beast (1965, Hideo Gosha)

The 1960’s really started to get into the swing and style, the fun of the samurai movie, while mostly maintaining the thematic integrity of the previous half century. And there is just so much going on in Sword of the Beast!

First, the visual style. It is so much fun to look at! It opens up with a samurai laying in the grass, as a gorgeous temptress walks up to him and seduces him. He looks up, and the men who are trying to kill him are a hundred or so feet away, so… Sure! Perfect time for sex. She is a femme fatale, though, and gives him up immediately. He’s on the run, and will be for the duration of the movie.

The sword fights are sharp, crisp, and frequent, heightened by a score that that has a lighter, fun quality about it than the traditionally dark and serious strings and drums of the 40’s and 50’s.

This movie is out to entertain. Our hero looks around his lodging, finding all the entries and exits, sitting in his bed and seeing how far his sword will reach in case the room is breached (which it immediately is, of course). These fun little tidbits are the gold of action movies, which is what makes it so surprising when the movie reveals itself to have some actual depth.

A lady murders someone for no other reason than greed, and attempts it again on our hero. Her cruel and unusual punishment is rape. The movie pauses for just a second to think about it. No one in their right mind would say anyone deserves rape. She did murder someone. While this is obviously some sort of comeuppance that the universe imparts on her, no one has to (dis)agree with the universe.

The themes throughout this movie are all about grey areas, and in that way, Sword of the Beast is thematically a noir. A soon-to-be samurai and his wife are hunting for gold, and she’s taken hostage. “Give us the gold, or we’ll kill her!” And he gives her up, as is what he thinks a samurai should do under the circumstances.

The gold, after all, is for his clan. This is a bad dude by most standards. But at the end, he gets a second shot at this same scenario, and makes the right call. But he only did it after disavowing his clan. Were his motivations really pure, or was there simply nothing left in his life to care about? Tough to say.

It’s also tough to call the final scene, when the hero walks past a girl whose father he killed. She’s been seeking vengeance on him this whole time, and after he saved her life and proved himself to be a good guy in other ways, she…

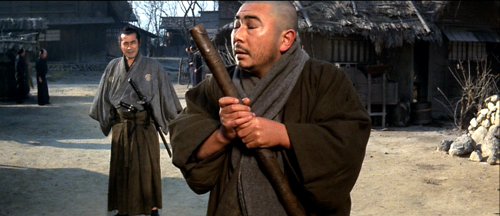

9. Samurai Rebellion (1967, Masaki Kobayashi)

It must be pretty easy to fall in love in Spain, a country known for outlawing unattractive people. Likewise, it must be pretty easy to be a cinematographer in Japan, a country which presumably outlawed ugly locations. Samurai Rebellion is as beautiful as it is tense, bittersweet and dark. How ingrained is duty to society in a culture, when a movie about killing your son for your boss raises questions? Maybe Mifune was Abraham, and the shogun was, what, god? The shogun isn’t even the highest guy on the food chain!

This is a pretty easy one to call “great,” and it does get mentioned sometimes. Its swordfights are among the most tense and breathtaking, with dutch angles abounding so blatantly that they’re easier to digest than they are in The Third Man, which unsuccessfully seeks to hide them. The deep focus is startling, because what’s captured in the background is, unusually, a beautiful landscape, not more characters in a room. There’s little narrative driving power to it, which turns it into more of a poem, a thought, than a story.

Kobayashi gives Mifune’s character an ultimatum. His boss wants his son’s wife as his own mistress, and Mifune, if he refuses, will surely either be murdered or forced to commit harakiri. He must decide if he wants to dishonor himself and his family by choosing his son and daughter-in-law’s love over his boss, or keep his honor by handing her over to be a whore? Would that really be honorable, just because everyone says it is?

He gives his son a message to tell everyone before the big showdown; his final statement to the world before his ultimate demise for siding with with family: “I, in all my life, have never felt more alive than I do now.”

10. Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (1970, Kihachi Okamoto)

The twentieth installment of the Zatoichi series is up against some legendary installments. A surprising amount of exploration went into the series, each movie exploring more layers of the blind masseur’s character, and toying with ways to stage action. Many different directors got their shot at it, and almost always succeeded. As a whole, the Zatoichi series may be the most cinematically successful long-running franchise in history. So when he meets the legendary Yojimbo, it’s no joke.

To be clear, Yojimbo is in Zatoichi’s world, not the other way around. He’s the antagonist. Not a villain, but certainly Zatoichi’s shadowy complement. They’re both in the grey area of morality; Zatoichi is nowhere near all good, and neither is Yojimbo all bad. And, while Mifune is right at home in a town’s bidding war for bodyguards, he finds a his most important companion and adversary in Zatoichi.

There are a lot of balls in the air, and they’re all juggled with ease. Everything is believable. Zatoichi and Yojimbo genuinely hate each other, and genuinely respect each other. They genuinely foil each other. Mifune is constantly blackout drunk, making fun of his clients, insulting Zatoichi for being blind. He tricks Zatoichi, hanging from a ledge, into thinking he’s thirty feet in the air, instead of actually only a few. They sic mercenaries on each other, which means they literally do want the other person dead. Just not enough to to have a showdown.

The battles are violent, the characters’ motivations are all for greed– wait a second. This evil Mifune character, “Yojimbo,” is motivated by love even more than Zatoichi is! And Zatoichi falls in love every damn movie, so it’s not as if the audience should take this particular love interest of his any more seriously than the rest.

Showing where the nameless Yojimbo character is after a couple of decades poses another ball in the air: to make him interesting, it’s probably appropriate to give him a backstory and a different motivation. But doing so spoils the mystery, right? Not in this case. His demeanor from the Kurosawa movie is his character, and it’s not that hard to see such a shadowy character become a drunken gangster after a while.

But is it possible that, by humanizing him and showing why he was the way he was in Kurosawa’s movie, that we may be able to forgive him? Maybe, if he just wants love? Well, thankfully, Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo doesn’t cop out and ask for your forgiveness. Kurosawa would be proud.

Author Bio: Patrick works full time in childcare. He spends his free time pursuing adult hobbies, such as writing about his favorite movies.