Pulp Fiction is still a frequent feature on many scriptwriting and favourite film lists. Perhaps it doesn’t quite seem it like it but well over 20 years have passed since the film’s release in 1994.

Earning many accolades and rave reviews for best screenplay, for many, the film and its scriptwriter Quentin Tarantino’s style (it should be noted here that the story was co-written with Roger Avary), crystallised a new dawn in screenwriting and the aspirations of many film enthusiasts eager to make it big.

Some critics and academics have drawn attention to its post-modern nature, some with the slightly doubled edged compliment of being a successful exercise in ‘turning pulp/shit into gold’. Over time it has become almost a rite of passage ‘must see’ for any screen or story telling enthusiast.

This list aims to take a practical and retrospective look at what an eager scriptwriter looking to make it big might learn from Pulp Fiction now. Was it all really so new and what, with the passage of time, can it still teach us:

1. Sequence Approach to Structure

Writing a feature length screenplay might seem a daunting process, Pulp Fiction itself runs to 154 mins. As a very general rule, that is one page per min and double the number of scenes. For the writer there is a fear that with so many scenes will it all make sense, will there be enough story, will every scene advance the story and/or reveal character without treading water.

Pulp Fiction’s fragmented and interwoven narrative style may seem a complicated example at first. However, the overall film is better considered in terms of its separate stories. One might argue that Pulp Fiction is (by premise) more of a portmanteau or anthology film (it was partially inspired by Mario Brava’s 1963 film Black Sabbath, itself comprised of three separate stories).

In this sense Pulp Fiction highlights a sequence approach to structure, this being sequences of scenes each with a common thread or brief focus (almost like a separate self contained story).

This is something McKee draws attention to in his ‘guide book’ Story. Consider each separate story in Pulp Fiction as a sequence. Whilst there is an overarching story or main hook to keep the audience in long term suspense, the briefcase or the opening robbery which the film returns to being two examples, the overall script is in effect built from separate sequences.

Notably, The Shawshank Redemption, released in the same year as Pulp Fiction and to less initial critical acclaim, can be viewed as mechanically very similar. Two other very different film examples which work this way are Withnail and I and even Lionel Jeffries’ 1970 adaption of the Railway Children. However, most films have clearly identifiable separate sequences each with their own main challenge/conflicts for the character(s) and can be de-constructed/constructed in this way.

The challenge for the writer is deciding the order of the sequences and, particularly in the case of Pulp Fiction’s non-linear narrative, not overlapping or contradicting each other. However, this should be far simpler than ordering scores of separate scenes in a long chain.

This sequence approach should allow the writer to maintain a more intense focus, maintaining audience interest throughout a longer script and avoid the risk of treading water at some point in the second act.

2. Approach Non-Linear Narrative with Caution

One feature of Pulp Fiction’s narrative many will instantly recall is the non-linear pattern the narrative adopts. The audience see the beginning of the final scene at the start of the film only to return to it at the end.

The stories or sequences which make up the bulk of the film do not play out in chronological order. In 1994, this may have seemed a fresher concept to many viewers perhaps more accustomed to the use of simple and brief flashback in both film and television, at the time it was something of a selling point for the film. Even now it still holds as a talking point.

Arguably here in Pulp Fiction, it made the film feel ‘clever’ as well as genuinely different, it at least felt like the first of its kind. Others followed this similar pattern, notably Guy Ritchie with films such as Snatch. On a plus-side it also gave these films a fast-paced feel which they may have lacked if playing out chronologically. Audiences at the time liked this, perhaps if the film felt fast-paced and clever they also felt the same.

One could say the high point of the ‘non-linear boom’ was 2000’s Memento, effectively an entire film told in reverse order. The criticism here is that, rather like many observed of Memento if played ‘backwards’ or in order, are these films just constructed of rather uninteresting/tame plotlines made to appear as though they have more twists and turns by the fact they play out in a jumbled order.

As a counter argument it is possible to state that rather than being viewed as a conventional crime/thriller told in an unconventional way, Pulp Fiction could be viewed as a fresh way of approaching an anthology film. Similarly, all these films do create suspense and mystery by using the non-linear approach to reveal and withhold information to/from the audience.

The lesson here for the writer is cautionary, regardless of arguing over the approach being either genius and/or gimmickry, non-linear now well explored and to construct a script using this premise is to be walking over covered ground the audience will be all too familiar with. The bar when adopting this approach has long since been raised – audiences now will expect something even cleverer from the format.

3. Book-Ending

Again on the subject of narrative structure, many observed that Pulp Fiction has a ‘circular’ narrative – returning to the ‘beginning’ for its final scene. In returning to its point of origin, the diner and impending robbery, it neatly ‘bookends’ itself. This technique is nothing new; it gives a story a tidy, self-contained feel (rather like physical bookends).

It also allows an audience to consider just what change/narrative journey has taken place since the last time the film was at said location. They should approach this feeling some knowledge/progress/insight has been gained.

In Pulp Fiction, the audience return to this point slightly earlier than the film’s opening thus allowing for a little added suspense regarding the forthcoming robbery. Many narratives go full circle, both geographically and in terms of characters/situation, in this instance Pulp Fiction offered nothing remarkable.

However, unlike many of the ‘low-rent’ exploitation which doubtless influenced its creator, bookending avoids the audience leaving the cinema feeling an ending was unnecessarily abrupt, strange, too open or feel like it made itself up as it went along – something many cult films do.

This method therefore gives Pulp Fiction an element of quality and craft, going against the grain of ‘cult’, indicating that it always had a film literate, more mainstream demographic as its target audience. Book-ending is something the screen-writer should keep in mind.

4. Don’t Over Explain Everything

Bookending may be a step toward quality but tidy resolved and fully explained twists which offer little by way of opportunity for discussion do not fair well in an age of internet discussion. As mentioned, one of the characteristics of a cult film is the tendency toward the unresolved, the unexplained and the cryptic.

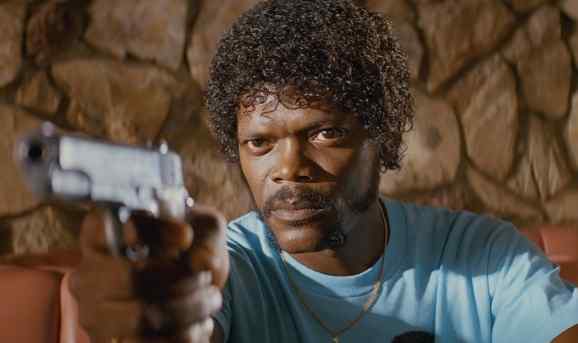

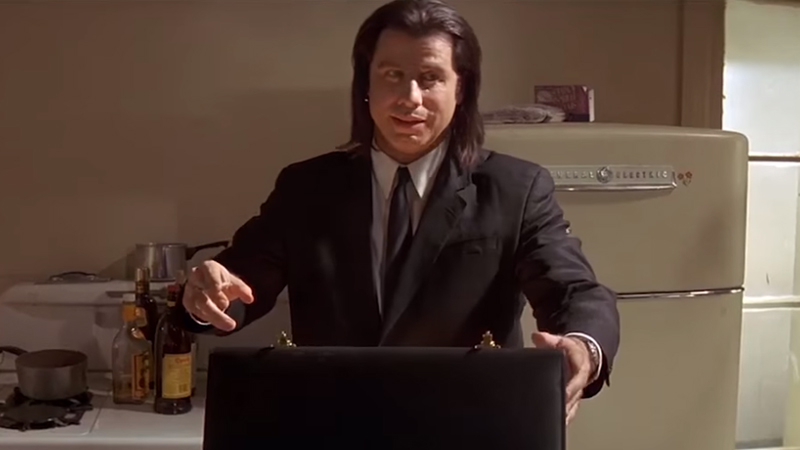

Arguably, Pulp Fiction arrived just as the internet was about to become a dominant force in fan interaction and discussion, much of the film’s continued popularity and ‘mystique’ is doubtless via repeated internet discussion. A quick search reveals various different theories concerning the contents of the briefcase.

None of this would be possible if Tarantino had written an explanation or revealed its contents. This highlights a lesson in not over-writing, the contents do not need to be explained, the audience are given enough to know the contents are important/valuable to the characters it concerns and that is all that is needed to keep the story moving.

The writer should aim try to move in light brush strokes, keep the pace up when needed and be wary of anything which may stall the narrative flow with unnecessary exposition. Modern audiences need only a few visual signifiers to get a point across, with Pulp Fiction Tarantino demonstrated he was well aware of this.

From a practical screenwriting point of view, the briefcase is a McGuffin, a device to propel the plot forward. From a 21st century point of view, it represents a perfect foothold in ensuring continued debate and cult interest in the film, either by intention of happen-stance Pulp Fiction demonstrates how this can be achieved. The secret of being a bore is to tell everything.

5. Sub-Culture

Audiences are there to be entertained. This entertainment often comes from an escapist journey into another ‘world’ or social sphere. The majority of viewers of Pulp Fiction will know little of the real world of hit men and mob bosses other than in other films/TV shows.

Here the film offers the vicarious thrill of a journey into another world. This world may well be a slick heavily stylised facade which bears only a cinematic resemblance to reality but for the audience it represents an entire sub-culture or alternate reality which runs parallel to their own. If a modern audience perhaps no longer believe in fairy tales and secret doors to magical realms, they will be more willing to accept these more tangible alternate realities running parallel to their own.

The writer should be prepared to seek out fresh sub-cultures, ones audiences will be find both entertaining and informative, realms they may wish to journey into and explore. Importantly for the writer, research it well and make it ‘real enough’ for the screen audience.

Point Break (1991) did this with surfing as did its ‘reimagining’ The Fast and the Furious (2001) with illegal street racing. However, do keep in mind, Pulp Fiction already has the mobsters, drug dealers and hit men box well ticked.