Released in 1976, Director Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver received much recognition at the time, being nominated for four Academy Awards and receiving that year’s Palm d’Or at Cannes, whilst it is still regarded as one of the greatest films of all time in the eyes of both audiences and critics.

Whilst writer Paul Schrader was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Original Screenplay, the first draft of which he apparently wrote in under four weeks. Here are 10 lessons a screenwriter can learn from Taxi Driver:

1. Don’t be a Bore with Backstory

A writer may compose a detailed biography for each character; for the most part this is to aid the writer in understanding the character. It does not mean the audience need to be subjected to it as tedious opening exposition or witness it line for line in an ‘emotionally revelatory’ scene.

The background information (backstory) we learn about Travis (Robert DeNiro) is fleeting and questionable, early in the film he states he was in the Marines, an ex-serviceman, there are the letters to his parents, whom the audience are to understand are both still living and celebrate their Wedding Anniversary in July.

Travis is potentially a highly unreliable narrator; the audience come to know he lies in these ‘letters home’ (if indeed they are ever sent) concerning both his job and his relationship with Betsy (Cybil Shepherd).

Therefore, if this backstory is to be believed, it is sketchy at best. The point here is that it does not always matter – this sketchy information creates enough of an image of his past, or his imagined past, to generate some understanding of his present, open to the interpretation of the individual audience member.

Perhaps Travis was in the armed forces, discharged for whatever reason, possibly as the result of, or resulting in, psychological problems, isolated from his family, whom he feels ashamed to tell the truth. The audience do not get a detailed conclusive explanation because the plot does not require one, what is implied offers enough explanation, how this is interpreted generates speculation and curiosity within the audience to keep them watching and thinking.

Taxi Driver would be a lesser film if it featured an ‘aftermath’ police interview sequence providing the viewer with all this. The writer should not be afraid to make the audience do some work, make them use their own imaginations, perspectives and experience – forty years after the film’s release and the discussion it still generates proves there is mileage in this.

2. Sometimes It’s What Characters Don’t Say

Raising the issue of dialogue when discussing Taxi Driver from a screenwriting perspective is a little awkward – it features one of the most quoted lines from cinema:

You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin’ to? You talkin’ to me? Well I’m the only one here. Who the fuck do you think you’re talking to?

This speech was not scripted; it was improved for the scene by DeNiro, apparently inspired by Bruce Springsteen responding to his audiences’ cheers at a recent concert. Critic Roger Ebert regarded this scene as representing ‘Travis mimicking the kind of effortless social interaction he sees all around him but does not participate in’. However, a study of what Travis does not say elsewhere in the film yields just as much insight concerning his character.

Consider his ‘4 O’clock meeting’ (although sources sate aspect of this scene also arose from improvisation) with Betsy, unfamiliar with each other they chat, the conversation is a little stunted but flows reasonable well. This alters as Betsy fails to immediately understand what Travis’ reference to ‘organas-ized’, realising her mistake she eventually responds by relating this to a ‘thimk’ notice as something commonly found in offices.

Travis does not reply, his lack of verbal response informs the viewer he does not know, nor does he have any point of reference or ability to relate-to what Betsy speaks of. There is a chasm between the worlds of these two characters. The absence of Travis’ reply is there for the viewer to see – a secret they share with him – providing them with part of the intrigue and puzzle of his character. Information conveyed by what he does not say and when he does not say it.

A similar example occurs earlier in the film, Wizard (Peter Boyle) tells a lurid sexualised anecdote, Travis listens in but does not interject, a line concerning a muddled boundary between sex and love triggers laughter for his peers but Travis only feigns a smile, unable to differentiate and relate to the humour here. Similarly, later in the scene, his attention drifts from their conversation as he fails to reply, instead staring at the fizzing aspirin in the glass.

There is some speculation here, is Travis merely distracted or are these clues/symptoms correlating to his underlying psychological issues. Regardless, this information is conveyed via the absence of, or breaks within, dialogue. The writer should consider when to halt the conversation in favour of pauses, beats, hesitations and awkward silences – these can speak volumes in themselves.

3. Lessons in Dealing with a Lone Protagonist

In the medium of show don’t tell gaining an understanding as to a character’s inner psychology is tricky. Travis Bickle is a loner, (a character with no confidents) perhaps one of the most immediately recognised in film history, and furthermore he is one with a complex inner psychology. Here Taxi Driver runs through a variety of methods to deploy this more cinematically.

The diary and/or the letters home to his parents, these offer the most immediate insight into Travis’ inner thoughts when used in conjunction with voice over – Travis narrating his own words as he writes.

Later this voice over is used over the top of other action, the audience’s understanding of what the voice over signifies is established, it becomes a useful tool in keeping pace and clarifying mindset – even when it is clear these words contradict some of the events – creating intrigue and suspense. What is important to note is that the audience share these lone moments and inner thoughts with Travis, allowing a bond to form, keeping them engaged, simple but effective.

Of course, voice over needs to be used with caution and where relevant, misuse can intrude upon the viewing experience and even veer into parody. Taxi Driver is a story concerned with psychological issues so the use of the voice over to provide an inner voice has relevance.

It should also be noted that Travis is alone but there are functional and/or frequently failed interactions with other characters (as covered above), these ‘conversational cul-de-sacs’ serve to indicate how lone the character of Travis really is. Importantly for the audience of a feature film, they also add some texture to the narrative. On screen, no audience can tolerate a character being ‘an island’ for too long, think back to Cast Away (2000) – even Tom Hanks had Wilson.

4. Grey Hats

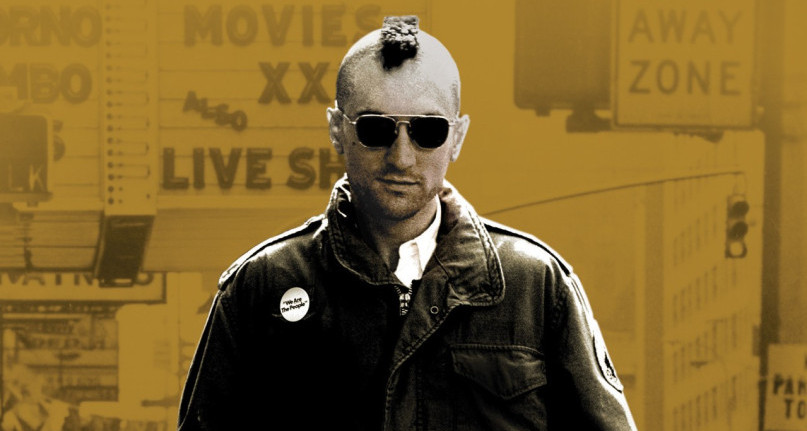

Is Travis hero or villain, a question still pondered to this day, as James Berardinelli argues, the end of the film would apparently see him as hero, but if his assassination of Senator Palantine had been successful he would have been very much the villain. Heroes in white hats with the bad guys in black hats is an oversimplified way to look at life, so have can an audience really be expected to engage with characters developed in such a way.

Travis’ story plays out in shades of grey, prompting questions ‘is he a bad man who does good things or a good man who does bad things’ – what’s the difference. Perhaps Travis is unable to understand the grey areas, viewing all as in terms of black and white.

Curiously, Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down (1993) could be understood as expressing this same question in a similar way 17 years later, with critics expressing doubt that in this instance the protagonist could be ‘both hero and victim’.

Either way, the tension and curiosity this creates helps keep an audience watching and re-watching. Complex, credible characters tend to be the ones in the grey hats, the ones the audience latch on to and question. Travis’ iconic popular culture status as an ‘anti hero’ could be seen as affirming this.

5. Arena in Tune with Character

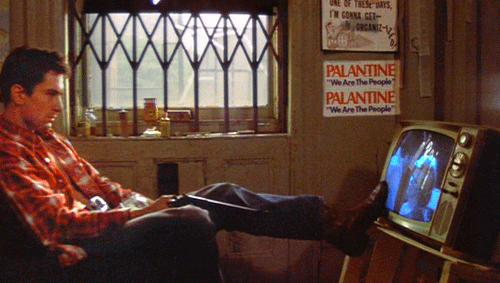

Like any script the ‘arena’ (the world of the story) within which the film takes place should not be overlooked by the writer. The New York City streets in Taxi Driver could be said to have a character all of their own. However, for this example attention is drawn to the ability arena as visual exterior can have to represent a character’s interior ‘head space’, something which runs in tune with Scorsese’s admiration of the German Expressionism film movement.

Consider the streets within the film; grimy, dark, undesirable areas of poverty and violence, desperation and skewed morality; these are the streets Travis frequents – the streets many of the other cab drivers would rather not work. In contrast, the bright sunlit streets of the day time feature not only Betsy, something of an unattainable romantic ideal for Travis, but also the enthusiasm of a political campaign.

The day time streets can be understood as representing the flip-side to those at the night time, a representation of hope and optimism for what might be, if misplaced or unattainable.

These film’s streets, both night and day, can be understood as visualising Travis’ troubled mental state, an approach which immerses the viewer within this mindset. Arena should not be overlooked as simply where the story is set, Taxi Driver teaches the writer that it can offer an additional means by which to visualise the internal.