6. Doppelgangers

A doppelganger is a ‘double’, the phrase taken from Germanic folklore literally meaning ‘double-goer’ or ‘double walker’. The concept of a double, either a physical or, in the case of Egyptian mythology, a spiritual ‘twin’ occurs within story-telling throughout the globe from ancient history to the evil twin/sibling perhaps more frequently shoe-horned in as a plot contrivance in contemporary T.V drama. Consider here Travis’ sketchy backstory, his present situation and his fascination with meeting and eventually saving Iris.

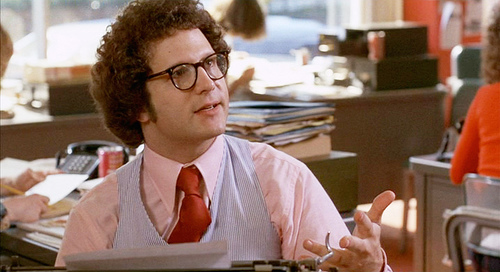

The information the audience learn of Iris (Jodie Foster) and the route to her current situation is possibly not too dissimilar from that of Travis, their current situations, lonely lives working through the night as components of a service they offer to others also bear some comparison.

Hence, one could say Iris is Travis’ doppelganger, a character used as a device by which the audience witness Travis view an aspect of himself, possibly his younger self, mirrored back towards him. Structurally, considering Iris as a doppelganger recalls the ‘you talkin’ to me’ scene in front of the mirror, raising thematic questions, is Travis trying to save Iris (himself) from an aspect of himself?

An encounter with a doppelganger typically brings bad luck, or death, in Travis’ case, depending on how one interprets the film’s ending; it does bring about large scale dramatic change. In this sense, Taxi Driver offers an example of how a doppelganger or the concept of a doppelganger may be used as device by the writer to highlight aspects of a character to themselves (and the audience), serving structurally as a form of character-driven catalyst to move the plot forward, as a character brings about dramatic change.

7. What’s in a Name

Character names can carry all sorts of connotations; the current popular culture perception and fashion may dictate these to some extent – for example when choosing a dull uneventful name for a boring hum-drum character. The name of lead characters within feature film scripts is worth giving some added thought in terms of enhancing the thematic depth of the story.

Consider Travis, a name derived from French, meaning to cross over, a name given to toll collectors on bridges and waterways. The name Travis is therefore rather apt for a character employed a taxi driver, taking payment to transport people,

it also suits one who could be understood as fluxing between two, or more, states of mind, ‘crossing between’ thus adding some further means by which to interpret the film’s events via its use. Iris also yields some interesting interpretation as the name of a Greek goddess who was the personification of the rainbow (where the iris as part of the eye is derived from), the boundary between the sea and sky.

Of further relevance here is the information that Iris also carried a pitcher of water to put to sleep all who swore false oath when crossing the River Styx (the boundary between the mortal word and that of the Gods). It would seem that both Iris and Travis are names derived from travel between one ‘world’ to another.

What these worlds are within the film is open to debate, does Travis himself ‘cross over’, again open to debate. What is important here is that these names allow for further depth and discussion, they also indicate that the writer knows their story and is conscious of the nature of the story they are telling. A bonus point here also for harnessing knowledge of mythology to help inspire and/or add gravitas to a script.

8. Narrative Spirals

Just how should a writer end a feature film – abruptly ‘when the story is told’ (see remarks concerning Hitchcock’s Frenzy in another list) or with an ‘epilogue’ to neatly round off all the story strands, Lord of the Rings: Return of the King (2003) perhaps took this approach to its most extreme.

The ending of Taxi Driver is open to various differing interpretations, some believe that Travis is killed in the shooting and the final epilogue represents his dying dream. Some consider the who film to be a ‘dream state’, this would certainly fit in with Scorsese’s comments regarding film in general (see ‘Remember to Be Creative’ below).

As Roger Ebert observed ‘the end sequence plays like music, not drama: It completes the story on an emotional, not a literal, level. We end not on carnage but on redemption.’ Others consider aspects of the final epilogue, particularly Betsy’s ride in the cab in which she praises Travis, as all taking place as part of a fantasy within his own mind.

Here James Berardinelli’s comments concerning ‘the vagaries of fate’ recognising that Travis could just as easily been ‘reviled as assassin’ and not built as a hero’ need considering in relation to writer Paul Schrader’s views that ‘he’s not going to be a hero next time’. Schrader has also stated that he envisioned ‘the end frame could be spliced to the first frame, and the movie started all over again.’

Here Taxi Driver offers up an example, not only of how to end a film, but also how one might consider approaching a screenplay’s narrative arch. Schrader’s views would suggest a narrative ‘bookending’ – the plot has come full circle, one story has done a complete revolution and punctuates its ending almost visually. However, by the same logic ‘next time’ is about to begin, another revolution of the ‘story wheel’ in which quite possibly Travis will not be ‘the hero’.

Rather than thinking in terms of just one revolution of a wheel, imagine spirals – the situation escalating, becoming more intense, the stakes higher each revolution. In a similar way, spirals can also be observed within the narrative – connecting with Betsy does not work out for Travis so he focuses on Iris – the high stakes assassination killing fails, this advances into the even higher risk (to his own life) ‘rescue’ of Iris.

All the time to situations escalates, as Scorsese has remarked, Travis is a ‘ticking time bomb’, something implied with the final glare to the rear view mirror (again part of the kind of visual story telling a screenwriter should be making use of) – the situation will play out all over again with higher stakes.

Spirals are a useful way to imagine narrative patterns, audiences consciously or unconsciously recognise them, they allow the writer to take check of their story, is it advancing, has a satisfactory conclusion been reached.

9. Put Reality through the Kaleidoscope

Many pieces of screenwriting advise and general writing advise tell one to look at life through the microscope. This is all good advice, sometimes a great story may spring from an otherwise trivial day to day matter. Imagine doing that then exploring different perspectives on day to day life, throwing around strange and difficult events, encounters with different people you just can’t forget, the day to day news events large and small all around you, where do these fragments meet, where do they overlap – what ideas do they trigger.

Taxi Driver’s screenwriter Paul Schrader was initially inspired by the diaries of Arthur Bremer, a loner who shot and severely injured U.S presidential candidate George Wallace in 1972. Schrader also took inspiration from his own life, writing the script shortly after a difficult period of living in his car following the end of a relationship.

One of the more curious instances occurred whilst the film was in production; apparently Schrader met a real life, Iris, an underage prostitute with whom he and Scorsese spoke to over breakfast. Schrader recalled that the girl had an attention span of around twenty seconds. This meeting doubtless fuelled the breakfast/lunch meeting between Iris and Travis in the final film.

The point here is that ideas and inspiration comes in many forms, sometimes strange instances from our own lives make great additions to a script, giving a fresh perspective on events.

Taxi Driver plays out through the kaleidoscope that is Travis’ world and whatever particular physiological issues he may be suffering, the aspirin, the bank note, Betsy in the white dress (a running theme with Scorsese) – all his own fixations, when viewed in a script they might look throw away but they need to be there. The real craft for the writer is to know what works, what does not and how to make it work when it feels like should but won’t.

10. Remember to be Creative

Scorsese himself has stated that the idea for Taxi Driver arose as the result of a conversation regarding films being like ‘drug induced revelries or dreams’, he also recalls the desire for the film to create the sense of being in ‘a limbo state between waking and sleeping’.

Many of the points identified within this list echo this sentiment – the use of names and approaches with mythological reference (think in terms of Joesph Campbell’s works and the unconscious mind), the ambiguities of Travis’ character, the expressionistic use of arena to convey the internal, also the various interpretations of the film, especially the ending. In short, be wary of thinking in extreme binary terms – either ‘reality’ or ‘fantasy’, a writer shouldn’t limit themselves or a potential audience to expecting the Technicolor signpost to inform them they’ve arrived in Oz.

Taxi Driver offers a strong example of how a narrative can, almost literally, flow between and over these ‘boundaries’ to create a seamlessly imaginative, escapist, raw and contemporary screen world. If imagination is the limit a screenwriter (any writer) should not limit their imagination by forgetting to think creatively about a story which at face value might at first seem ‘grounded in day to day reality’. Got all that, yes, I’m talkin’ to you – now get writing.