6. An Inn in Tokyo (Yasujiro Ozu, 1935)

“An Inn in Tokyo” is a silent film about a family that lives in the industrial flatlands, a setup that is almost a precursor of the cinema of miscommunication of the early 60s. In this film, just like in De Sica’s film, we see a progressive sequence of events that will climax in the complete loss of dignity of a human when submitted by the dreariness of his misery.

The difference between Ozu and De Sica is that despite the tragedy and emotion of the events depicted, De Sica’s style is irregular and rough, to emphasize the anger that the director feels towards the situation.

On the contrary, Ozu’s camerawork never loses the incredible sense of the composure and serenity of Japanese tradition, the capacity to find beauty in misery as a moment in the long story of eternity. De Sica has the capacity to depict the moment and be as contemporary as possible, while Ozu has the capacity to establish communication between small social issues and the breath of infinity.

Ozu’s empathy for the poor transcends the social context and he focuses his attention on the general poetic sadness of an oppressed creature that is left with the capacity to dream, wish, feel, and be moral despite the almost full incapacity of surviving with dignity.

7. My Childhood (Bill Douglas, 1972)

Class attitudes in British cinema have always been an essential subject, and childhood has been crucial as well. The quintessential movies that explore these two themes are “Kes” by Ken Loach and the early films of Terence Davies.

Bill Douglas, in his films, took the subject and added autobiographical details and a sense of the magical and the tragic that makes it comparable to the late works of Jodorowsky, despite the fact that it lacks the visual inventions and is incredibly low budget and essential.

So vivid is the struggle, so relentlessly bleak the point of view of Douglas, that the film is elevated from a rigid depiction of social conditions to an eulogy to human life. Maybe it is the fact that Douglas was Scottish, but the sense of poetic brutality of every sequence, the smell of the industrial facilities and the landscape of the fields, along with the moving portrayal of the mother, achieve a level of melancholia that makes the film almost unwatchable.

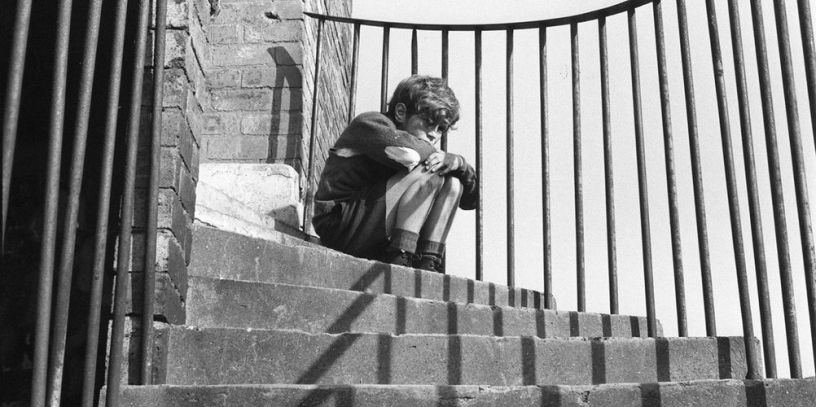

The film remains at ground level in its entirety, with tight close ups and camerawork that makes the viewer feel enclosed in the narrow streets and the narrow view of the world that characters carry with them. A lot of scenes take place with a concrete wall backdrop, staircases with rusty steps, and the smoke that lingers over the buildings.

The film’s tragic weight could almost remind people of something from a Thomas Eliot poem; the hollowness of the lives of these people is so absorbing that it is painful.

The moment of hope, of fabled ingenuity, is present in this film, in the form of a sequence where a kite is shown flying, not really moving, suspended in the same point at the center of the frame, almost undecided about whether it wants to go up toward the sky, away from suffering, or the gravity is going to inevitably bring it back down among the grey and green fields. The film is part of a trilogy dedicated to the childhood of the director, a major work of Scottish filmography, a Dickensian cinematic gem.

8. Yellow Earth (Chen Kaige, 1984)

Chen Kaige’s film caused an earthquake in Chinese cinema, kickstarting the Fifth Generation of Chinese filmmakers, and separating itself from the communist propaganda that was produced since 1949, giving up the idea that the government’s role was to help peasants in economically depressed and agricultural areas of China.

The film is set in Shaanxi and is about a soldier who is sent to collect folk songs from that area and lives with a poor family. Kaige shows the Chinese landscape with incredible harshness and a visionary talent that evokes the novels of Gao Xingjian.

In the film, the character of a young girl is present, again as a bright image in a nearly deserted landscape. The film is not completely dry and ascetic in its depiction of rural life but has quite a few moments in which it finds comfort in melodrama, and a sweeping soundtrack that gives a sense of being epic and the sense of the frontier, along with the high-pitched singing of traditional Chinese music that adds to the element of nostalgia.

Kaige’s eye is also extremely nocturnal in many sequences, showing the moment in which the shadows start to envelop the earth, the way in which the fire illuminates the night and the voices of singers echo infinitely. From that moment on, the tradition of cinematic realism grows and grows. In Chinese filmmaking, for him to reach the major heights of a film by Jia Zhangke, Wang Bing, Zhao Ling. Chen Kaige, made him, in his way, a pioneer.

9. Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955 )

The connection between Ray and De Sica’s films run deeper than any cinematic connection on this list. Ray was traveling, and while he was in London, he had a chance to watch “Bicycle Thieves”, and his life changed, as he decided to become a filmmaker and renounce his previously desired job. It is quite possible that the Indian filmmaker was able to surpass his master with his Apu Trilogy, of which “Pather Panchali” is the first installment; it’s a film that was extremely low budget, shot on location, and infused with lyrical qualities and the depiction of pleasures of simple life, the small pleasures that were defined as “epiphanies of wonder”.

Two sequences, the train sequence and the rain sequence, are enough to probably surpass most of the films ever made in showing the power of cinema, the power to elevate the trivial, the mundane, the material, into something sculpted in time, philosophical, uplifting, and magical.

10. The Kid with a Bike (The Dardenne Brothers, 2011)

This film is great naturalistic fairy tale, perfectly connectable with a film like “Bicycle Thieves”. The Dardenne brothers slightly departed from their essential naturalistic style to concede themselves a couple of flights of imagination and a lightness in tone that tips toward a brighter worldview.

Another incredibly obvious connection to the De Sica film is the bicycle, naturally. In “Bicycle Thieves”, it was an object aimed for the survival and the protection of the dignity of an already poor family, while in the Dardenne film, it is primarily a means of transportation that elevates the elegiac tone of the film into a few escapes into windy and sunny landscapes through the caresses of the breeze.

In “Bicycle Thieves”, the main character miserably stumbles trying to ride on a barely functioning bike that will lead him to mere survival; in “The Kid with a Bike”, the kid rides through the quiet night, his heart pumping blood into his muscles. He is a character on a journey that will lead him to something unknown; in the De Sica film, the journey can only be a cycle and can only lead to nothing.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.