The very idea of turning the camera around and using it to observe the creation of movies themselves has been utilised since the birth of cinema.

Filmmakers since have often explored the behind the scenes as a main source of inspiration in an effort to dissect their own work and examine how the process of filmmaking affects the lives of those who either produce or consume it.

Many of these sort of self-reflexive films were made around the time of cinema’s 100th anniversary in 1995, as a way to celebrate film’s firm stance in postmodernism and to commemorate the livelihoods of those who enhance our lives with their flickering images and synchronised sound.

1. Through the Olive Trees

This film from the late Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami that delves into the filmmaking process is a curious film in itself, but its place within a bigger picture makes it even more outstanding.

The accidental so-called Koker trilogy began with Kiarostami’s kids film Where Is The Friend’s Home? in 1987, which he followed up with a metatextual continuation with Life, and Nothing More… in 1992, which was a dramatisation of the director and young actor searching for the young actors from the previous film in the aftermath of the Iranian earthquake of 1990.

Then the metatextuality was brought up another notch with this film, which documents the filmmaking of Life, and Nothing More…, once again reminding us that what we are watching is still fictional and has still been performed and produced.

The story taking place within the film production sounds rather upsetting, which follows one of the actors on the film set who proposes his love to an actress who was recently orphaned due to the earthquake, though she takes offense to this as he is poor and would not be able to support a family.

This sounds cruel, especially for another quietly naturalistic and easy-going Iranian film, though the on-set story continues with the actor taking advice from the director on not just how to perform in the scene with the actress, but how to gain her attention and woo her.

Through the Olive Trees is the most reflexive film of the trilogy, the one that looks most squarely at how the filmmaking process affects the lives of those involved in it. But each of these films are worth checking out, in no particular order, as this trilogy was groundbreaking for Iran’s place in cinema, revealing a philosophy shared by other fellow Iranian filmmakers that the truth was the best source of inspiration for these “fictional” films.

2. Living in Oblivion

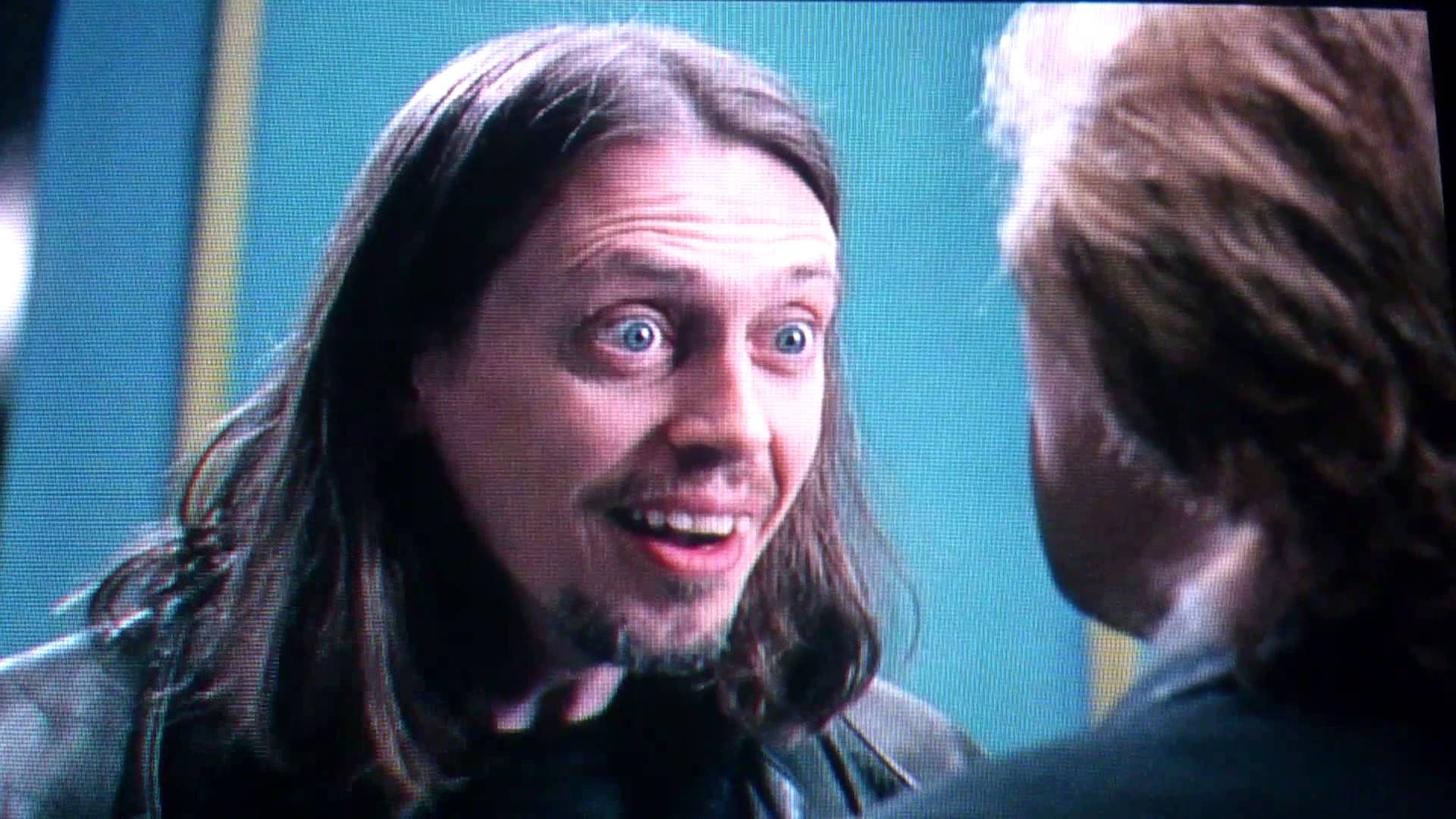

The nightmares of (very) independent filmmaking are revealed in all their horrifying glory in Living in Oblivion. Split up into three different segments depicting the troubled shoots of three different scenes, Nick (Steve Buscemi) is like any other director, head-strong about getting his film shot despite any problems that arise along the way.

Sometimes these issues are small, like unfocused lens work, actors forgetting lines, or exploding lights — and others are much more problematic, like actors wanting to change Nick’s vision mid-shoot or becoming so disillusioned with his work, they quit.

Many of the possible errors and unlucky circumstances that could possibly happen on an independent film like this do go wrong for poor Nick, and it’s likely only Buscemi could’ve conveyed this sort of pent-up frustration of someone who’s in a position to want to yell at all his workers, but can’t (because they’d leave his set).

Living in Oblivion is an often amusing film, made more masochistically amusing for those who are active in the independent filmmaking world, and it remains in the film shoot for its entire duration as we spend time to witness this colourful cast of characters and their unusual interactions and relationships with each other in one of the most hostile and pressurised settings there can be – a film set.

3. Close-up

When Hossain Sabzian was convicted of fraud when he passed himself off as the aforementioned Mohsen Makhmalbaf to a well-intended family, Abbas Kiarostami was wise to document this story as it occurred and was lucky enough to have the rather lenient legal system agree to let him film in the court trial itself, lights and boom-pole included.

Seeing this legal proceeding over a fairly unserious, yet unusual fraud charge is fascinating in how direct those involved are with explaining their case.

The family prosecutors explain in enough detail how Sabzian convinced them he was the director and how they eventually found out he was not who he says he was.

Some of these moments are left to our imagination (like Sabzian taking the family to see The Cyclist, a film they thought he had directed), though other moments (such as when he first meets the mother on the bus, as well as his eventual capture) are recreated on film and the easy-going quaintness of how these scenes play out match very well with the documentary footage – it’s not hard to believe that some people may accidentally see Close-up as entirely documentary or as entirely fictional.

Watching this trial, along with these appropriate bits of dramatisations, is fascinating for anyone whose only exposure to the legal system has been in Western nations (or through their films and TV shows).

It’s also eye-opening to see how revealing people can get in the court, with Sabzian giving more than a few humbly spoken, but resonating statements that convey his frustrated dissatisfaction with his own life and how participating in this rather cheeky and rather criminal act made him feel more worthwhile in the world, relating his emotions to the importance cinema has over the lives of people like him.

For any fans of the cinema, this is an essential “documentary”, one of the shining examples in the medium’s history of what an intoxicating effect films can have on people.

4. A Moment of Innocence

After the whole kerfuffle with Mohsen Makhmalbaf in Close-up, the director himself toyed around with recreated reality and how life inspires the greatest stories in film.

Drawing on his own experience, the film details the moment in a 17 year old Mohsen’s life when he stabbed a police-officer, Mirhadi Tayebi, at a protest rally and revolves around Mohsen and Tayebi themselves attempting to stage and film a dramatisation of these events.

Thus begins a quest for catharsis, hopefully both for the police-officer and filmmaker, though proves to be too much for the actor playing Mohsen, who cannot bring himself to commit the act of violence against the police-officer (again).

A Moment of Innocence is especially tricky and interweaving with its blend of fiction and reality, hypothesising on the emotional pressures and hardships of not just creating fiction, but recreating reality as fiction.

This metafilm mediates this troubling story and its stimulating recreation with plenty of subtle humour that revolves around how Mohsen and Tayebi now see themselves all those years ago when the incident took place, as well as Tayebi’s confessed acting aspirations.

Like with the other Iranian films on this list, A Moment of Innocence is one of the great films that examines the social and emotional importance that lies within filmmaking, which makes it a shame that this film (along with many others) was banned in its own home country.

5. Dangerous Game

One of the great American independent filmmakers, Abel Ferrara, coupled his uninspired Body Snatchers remake in 1993 with a far more revealing and far more interesting film on a far lower budget.

After a stunning performance in Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant the year before, Harvey Keitel gives a different, yet equally as demanding role as hot-headed director, Eddie Israel, who must deal with dramas on his film set and in real life.

He must deal with the diva, Sarah Jennings, appropriately played by Madonna in what is very likely her best cinematic performance – even though she is playing an actress who can’t act, she plays the hell out of this meta role, keeping her own against Keitel as they both impressively switch between their roles and their role’s roles, demonstrating how in control of their dual performances both are.

Also impressive in the same way is James Russo as Sarah’s co-star Francis, who clashes heads (almost literally) with her as his ego tells him he’s too above her to share a scene with this celebrity.

Typically for the wild yet deliberate Ferrara, he allows breathing room for the scenes of the filmmaking process by lengthening them out and to arduously show the collaboration, or disparity, of mind-sets on set.

These prolonged scenes are especially uncomfortable for the sort of masochistic performance Madonna’s actress role is playing, which gradually becomes a more sadistic benefit for Eddie and Francis – Sarah’s willingness to realise a dangerous performance is taken advantage of for all its worth by Eddie, to give more edge to his film, and by Francis, to complement and strengthen his own performance.

Dangerous Game shows an undeniable sleaziness in filmmakers who are earnestly striving for art, looking deeply and at length in this sort of inspired, though uncomfortable acting process in an up-front manner that not many other films have the strength to touch upon.