5. Many of De Palma’s best films are beloved cult films, not the Oscar-bait movies or blockbusters that his peers perfected

De Palma was part of a group of five directors––the other four being Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and Martin Scorsese––dubbed the Whiz Kids, who aggregated a genius generation of American auteur filmmakers.

“The Whiz Kids were American spinoffs of the European nouvelle vague of the early 1960s. They had been raised on the notion that the real auteur of a good movie had to be the director,” writes Susan Dworkin in her book “Double De Palma”. “The idea was that a director could take a genre movie…and so imbue it with his vision and technique that it would rise above the genre into the sphere of art.”

So while Coppola dove into his Godfather films, Scorsese explored the damaged masculinity on the streets of New York, and Spielberg and Lucas perfected the popcorn-inhaling exuberance of large-scale spectacle blockbusters, De Palma explored small-scale tales of teasing sex-horror, rock opera, seamy sexuality, and stirring satire. Something as schlocky and playful as Phantom of the Paradise, for instance, was never going to covet mass appeal.

And while other projects, like Blow Out and Dressed to Kill had the ingredients for populist profit––and many of these films did very decent box office––De Palma happily embraced Hitchcockian taboos and Buñuel surrealism, traits that were unfashionable or at least polarizing throughout the 70s amongst mainstream audiences.

While De Palma’s virtuoso skills were appreciated critically and amongst subsequent generations of filmmakers and fans, he was more often than not a cult director for niche audiences, even after films like Carrie would go over extremely well.

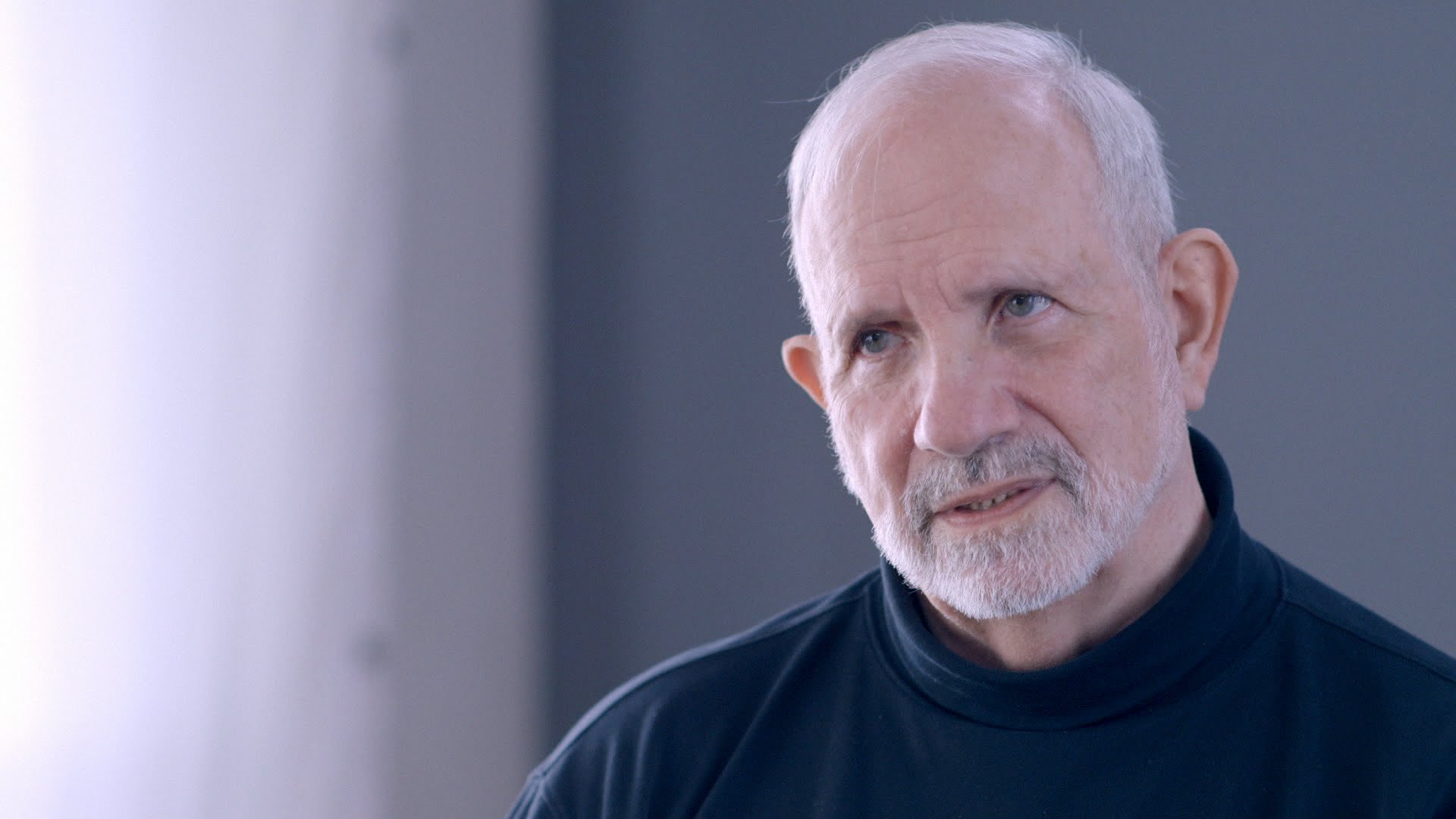

4. De Palma’s bold visual style and formalism

“I can still tell Brian’s work in a minute. His work is the work of a rational, thoughtful, intellectual person who stands outside things—and who, in fact, is the opposite of that, whose passions run deep, whose sense of outrage is limitless.”

– Susan Dworkin, “Double De Palma”

Intrinsically De Palma is unable to make unattractive films. A superb stylist and ardent visualist, De Palma has an unerring appreciation for the beauty of movement, roaming through spaces, across sparkling surfaces, and therein finding and serving purposes of pragmatic majesty. Pageantry amidst anarchy; just look at the Liberty Day parade sequence in Blow Out; the shootout between Sosa’s men and Tony at the climax of Scarface; or the Union Station scene in The Untouchables that pastiches the Odessa Steps from Eisenstein’s The Battleship Potemkin, to rattle off just a few.

De Palma is fascinated by the spectator role of the viewer and actively inciting the audience’s perceptions at deeper and deeper levels. With a Rashomon-like proclivity De Palma will frequently offer multiple interpretations of a single event, tossing in dream and reality intimations that blur symbols and imagery in wild ways.

So balletic and operatic is De Palma’s visual style that surrealism and imagination work as one. Body Double, for instance, is a chimerical spine-chiller that also shrewdly observes life in Los Angeles circa the mid-1980s. Certainly De Palma’s fearless lack of inhibition and his avoidance of didacticism makes him an authoritative pop satirist.

3. De Palma’s perseverance and tenacity demands respect

“You really are as hot as your last movie. And it goes away really quickly.”

– Brian De Palma

Even De Palma’s lesser works contain moments and sequences of sublimity and ingenuity. He’s the first to admit that The Bonfire of the Vanities represents a total cave-in to commercial annoyance and studio meddling and yet it opens with a stunningly choreographed 5-minute Steadicam tracking shot. The much-maligned Mission to Mars, a big-studio debacle still contains a handful of technically dazzling set pieces.

Yes, the finale of Snake Eyes is short of satisfying but the 20-minute opening sequence, another Steadicam coup d’état includes complex action and a cast of hundreds amidst a heavyweight championship boxing match in an Atlantic City arena. And for each of these duds De Palma still keeps coming like bone-weary boxers in Snake Eyes.

A film like Scarface may have only been a moderate success initially, but De Palma had faith in the project and it would go on to have a huge societal impact as well as it would land like lightening for the hip hop scene a decade or so down the road. Who could have foreseen that? And while his buddy movie black comedy Wise Guys fell flat with audiences in ‘86 he bounced back big time with next year’s The Untouchables (a huge critical and commercial hit that also made a splash at the Oscars and the AFI).

2. Not a “poor man’s Hitchcock” like some claim

Particularly with his suspense thrillers many of De Palma’s detractors suggested he’s merely a ripoff artist. For starters such claims are ignorant of how many other filmmakers have influenced him, from Buñuel to Eisenstein and Powell and Pressburger to Godard, amongst others. And similarly to Buñuel and Godard, De Palma has a tendency to alienate and annoy certain audience members simply because he’s too experimental. Too much self-reflection and contemplation can be toxic to viewers that don’t want radical, they want right now.

“De Palma does not copy Hitchcock, he follows him, and his films (specifically Dressed to Kill, Blow Out and, to a much lesser extent, Obsession, Body Double, and Raising Cain) are not imitation Hitchcocks, they are rather authentic and ingenious developments of the same themes that once obsessed Hitchcock,” writes Horsley in “The Blood Poets”, adding: “De Palma took the threads that Hitchcock laid, and then ran with them, in the process creating a whole new tapestry, and his audacity helped to resurrect the old horrors within new forms in the American cinema.”

It’s worth noting too that in the early and mid 70s, around the time De Palma was exploring some of Hitchcockian homages in works like Sisters (73) and Obsession (76), important films from the Master of Suspense like Vertigo, had yet to be widely recognized as masterpiece, nor was it widely scene outside of rare arthouse screenings. In pastiching Vertigo he was essentially reintroducing the film to a new generation of filmmakers and audiences alike.

“[Critics] want to deny the truth and drift off into total escapism,” writes Armond White. “That’s why they can’t see De Palma for anything other than a Hitchcock imitator. Some people think the world begins and ends with Hollywood formula; they aren’t aware of art, they aren’t aware of the modernist movement. But I think that’s almost willful. I mean, he’s been making movies for over thirty years (sic.) and they still deny his seriousness. But it’s worse than that, it’s a willful commitment to the Hollywood idea of ‘escapism is everything.'”

1. In his own words

Longtime De Palma fans already know and agree with what this list has offered and argued, new De Palma fans will get familiar with all of his quirks and accomplishments as they work through his deeply rewarding filmography. But since De Palma has frequently found himself in the hot seat as a provocateur, let’s allow him the final word.

“I wanted to tell tight, precise stories and suspense and terror sometimes lend themselves to that. I was trying to learn something about film technique. I’ve been influenced by the German Expressionists. I’m very concerned with motivating an audience through imagery. I think I’m one of the few directors working in that area, and a lot still has to be developed there. Visual imagery and sound are essential elements of a film. That’s what makes cinema cinema. Most directors use their cameras as recording instruments and don’t really get to the essential element of form.”

“So I like to try to go back and develop pure visual storytelling. Because to me, it’s one of the most exciting aspects of making movies and almost a lost art at this point.”

– Brian De Palma

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.