East Asian cinema has been enjoying its well earned and long yearned global recognition during the past couple of decades. Its diverse film traditions, once strictly typified by jidaigeki and wuxia movies, have finally succeeded to showcase that the directors who represent them can give birth to a wide variety of films that belong to a broad range of genres.

But what is this unique differentiator that lends modern East Asian cinema with its undeniable and essential appeal? The phenomenon of genre bending could be safely identified as a major component of this appeal.

Martial arts films with a twist of comedy and raw violence, horror films that turn out to be musicals and crime films that transform into heart-felt melodramas are not rare hors d’oeuvres in the rich menus that East Asian cinema has to serve.

The fierce invasion of Western culture, the repeated colonisation of the countries by foreign forces and the interplay between their local identities and global influences are only some of the factors that pushed the directors to create movies that break the established genre conventions, positioning them in multifarious cinematic categories simultaneously.

This tendency consequently helped to attract film viewers with different tastes, giving East Asian cinema the chance to surprisingly multiply its target audiences. The list below presents films that characteristically cross the boundaries between seemingly incompatible film genres.

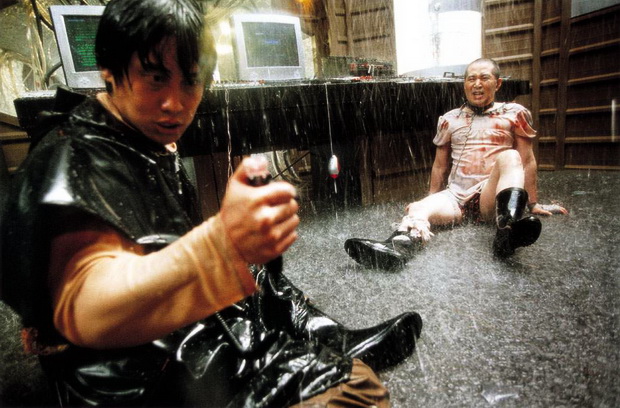

1. Save the Green Planet! (Joon-Hwan Jang, 2003)

South Korean cinema is the master of genre bending and Save the Green Planet! couldn’t be a more perfect example. The film starts off looking like a comedy, with light hearted music and a protagonist who is convinced that the powerful leaders of his country are evil aliens in disguise preparing for invasion.

He kidnaps the executive of a pharmaceutical company and starts interrogating and eventually tortures him in order to reveal the conspiracy that he is weaving. A detective steps into the game, investigating the rich man’s disappearance and the situation gets more and more complicated.

Save the Green Planet! jumps starts like a comedy, continues as a thriller and ends up being sci-fi. Furthermore a series of political and social commentary is hidden beneath its surface. The young man, who first appears to be a deranged, borderline funny, character is revealed to be a person with a traumatic past whose life had been forcefully taken away.

The amusing instances of the film abruptly make way for sequences practically painted with blood to shivering effect. At the end of the movie the viewer is left wondering if the paranoid man was not so paranoid after all.

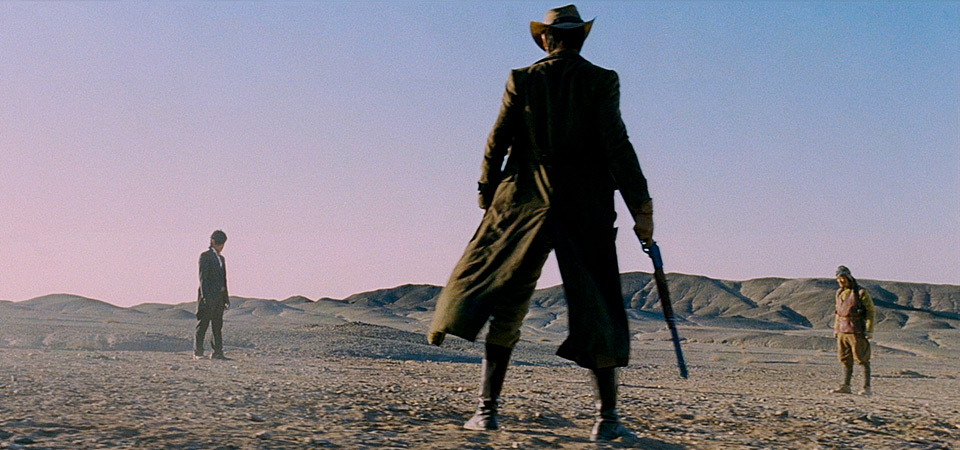

2. The Good, The Bad, The Weird (Jee-woon Kim, 2008)

Kim Jee-woon practically solely makes films that break the genre conventions. From his debut The Quiet Family, that kept its balance between a horror film and a comedy with hip-hop music, to his horror-family melodrama A Tale of Two Sisters, the director never fails to experiment and improvise, offering something fresh and new. The Good, the Bad, the Weird is his hilarious translation of a cowboy film featuring some of the most famous South Korean actors (Kang-ho Song and Byung-hun Lee among them) on horses clutching lassos.

A just bounty hunter, a ruthless criminal and a clumsy robber all share the common quest of retrieving a hidden treasure during World War II. The Japanese army and the Chinese military steps into their way and the outcome is a vivid action film with fair doses of humour and emotion.

The description may make the film sound naive or absurd, but that is hardly the case as Kim’s treasure hunt/train heist movie carefully keeps one foot in the realm of art-house cinema, as it is clearly well informed of the cinematic traditions that it employs and utilises.

3. The Happiness of the Katakuris (Takashi Miike, 2001)

Takashi Miike is another colossal East Asian director that favours to experiment with his films. His cinematic violence, always present in his artistic vision, is eloquent enough to deliver emotional nuances that expand from pure terror and disgust to passion and exhilaration. The Japanese auteur never fails to surprise with his grim imagination and substantial absurdity.

The Happiness of the Katakuris is a film based on Kim Jee-woon’s The Quiet Family, narrating the story of a family that opens an inn on the side of a mountain only to witness all of their visitors dying one after the other in unexpected and surrealistic ways.

Even if death is all around them, the members of the family don’t lose their appetite for dancing and singing. There are plenty of musical numbers in the film along with animated sequences featuring clay figures, all of them unique and refreshing, raising its craziness to profound levels.

The characters of the movie are all hilarious in their own way, with the best of them probably being a naval officer who presents himself as the nephew of the queen of England. Takashi Miike’s film is an ingenious pastiche of heterogeneous cinematic traditions and genres that exhibits the bottomless nuttiness of its creator.

4. A Chinese Ghost Story (Siu-Tung Ching, 1987)

A Chinese Ghost Story is a monumental film for the cinematic legacy of Hong Kong, followed by numerous movies who successfully or unsuccessfully decided to borrow from it. Its director, Ching Siu-Tung, is also the man behind the lyrical action choreographies of Zhang Yimou’s films The Hero, House of the Flying Daggers and Curse of the Golden Flower.

The film contrastingly combines elements that belong in various genres. It is a melodrama, a ghost film, a comedy and a martial arts film at the same time. The conflicting genres are blended with each other in a manner that keeps the viewer’s curiosity wide awake for what is about to happen next and masterfully maintains a balance between seriousness and cheerfulness.

The protagonist is a wandering debt collector who decides to spend a night inside an old deserted temple after running out of money. There he meets a beautiful young woman who steals his heart in a mystifying way. The man quickly realises that the girl is in fact a spirit, bound to serve an evil demon, and is determined to free her from this curse.

The cinematography of the film resembles a painting, the music fuses folk and modern rhythms and romance between the shy debt-collector and the ghost-maiden is moving and emotional in an unorthodox but original way.

5. All about Lily Chou-Chou (Shunji Iwai, 2001)

All about Lily Chou-Chou is undoubtedly one of the most untypical coming of age films ever made. Revolving around the unstable lives of two adolescent boys in Japan, the film employs music and cyber texting as platforms that mediate its narration. This unconventional storytelling choice perfectly serves the establishment of multiple narrative time levels that lend the movie a complicated but coherent structure.

The story of the two heroes begins in medias res only to jump to the past and then again to the present. The hybrid composition of All about Lily Chou-Chou is furthermore enriched by the different genres that it evokes; a drama to its core reminiscent of an ambient video-clip and a documentary.

The film offers a depiction of the every day life of the young boys, showing how their personalities change as they undergo major personal and social changes. Family problems, peer pressure and a shifting environment drives them to negotiate their relationship with themselves and the others around them. The music of the fictional artist Lily Chou-Chou operates as a constant meta-commentary on all of these drastic fermentations.

A bonus interesting feature of the film is the fact that a fair amount of the cyber conversations that take place in Lily’s fan site belong to actual people, as the film was part of a project that the director constructed around Chou-Chou’s fictional persona.

6. Daisy (Wai-Keung Lau, 2006)

Daisy could be just an average melodrama using tropes that often remind of a soap-opera. There is a love triangle in its centre consisting of a young artistic woman and two men, one of them is an Interpol agent and the other a hitman, and lots of drama that springs from their interactions.

The girl is working in her grandfather’s shop in Amsterdam and spends her free time drawing portraits of people in a square of the city. Both of the man fall in love with her and try to attract her with a tragic outcome resulting from their collision. The director of the film is the man behind the Infernal Affairs trilogy, a fact that partly justifies the unexpected crime/action elements of the movie.

As it was stated above, Daisy is a borderline soap-opera. The girl has the dream to become a painter, she only has her grandfather to support her and she is lonely but kind.

The otherwise ruthless hitman secretly sees her on an idyllic spring day, when she accidentally falls into a river and decides to build a bridge for her to prevent her for falling for a second time. He also starts sending her daisies every single day, an act that the heroine interprets as a love gesture from the part of the second man, the Interpol agent, with whom she falls in love.

The scenes where the viewer gets to see the men pursuing their respective crime-related occupations, being professionals above anything, else seem to be a cacophony to the overall romantic atmosphere of the film. There are shootings, a drug cartel pursuit and lots of scheming. All of the aforementioned features contribute to the construction of a hybrid crime soap-opera, typical of its South-Korean origins.

7. Love Exposure (Sion Sono, 2008)

Refreshingly excessive and restlessly provocative, Sion Sono is anything but a director who would respect and adhere to genre conventions and restrictions. Having repeatedly expressed his disapproval of traditionally praised Japanese auteurs , like Yasujirō Ozu, and the film traditions they established, Sono enjoys mixing and twisting different film influences and styles.

Pretty much any of his movies could be identified as genre-bending, but Love Exposure is probably the most characteristic of them in its subversive audacity. The film revolves around the life of a teenage boy who has to deal with his unpredictable father, a dynamic girl he falls in love with and a pseudo-religious criminal organisation. There is lots of street fighting, blood, paranoia and certain obsessions over female underwear.

Love Exposure flirts with comedy, drama, action, slasher genres and sub-genres and borrows heavily from the Japanese pinku-eiga tradition. It is pleasantly vulgar and even when it’s in danger of looking silly and naive, its originality saves the day. What is really surprising about the film is its capacity to evoke such a wide range of feelings and emotional reactions.

Goofiness, violence, love, hate and profound sadness; everything is present in Sono’s four hour long project. The genre-bending tendencies expand also to the film-direction techniques and music choices. The movie has steady frames, handheld shots, jump cuts and its soundtrack consists of Beethoven, bolero, j-pop and j-rock music.