8. Ousmane Sembène

Ousmane Sembène, a Senegalese filmmaker, almost single-handedly founded African cinema. His three films about the condition of women in society, “Faat Kinè”, “Moolaadè”, and “Black Girl”, are unmissable. “Black Girl” is a masterpiece, without question; it is a 1960 film that brought African cinema to international recognition for the first time, and is on the same level of great Italian and French art cinema of the period.

The protagonist of the film is incredibly tragic, in her beauty and her story, in her broken dreams, in her naivety and ultimate firmness in her last decision. The black girl is a symbol of all Africa, not just socially, but philosophically. Sembène takes the stereotypical portrayal of African by westerners, as people who are benevolent, natural and naïve, and explores the psychology behind those appearances.

The sea of discontent and tragedy that is in every woman who walks barefooted aimlessly looking for a job in Dakar, who sits on the corner of a street under the scorching sun, waiting to be offered a job by some hideous French woman, who then basically proceeds to de-facto enslave her. She feels treated like an animal, but she desperately exercises her free will in the last way that feels possible to her, and leaves the West haunted by a sense of collective guilt.

“Moolaadè” is a contradictory film, because it is shot in 2004 and yet deals with topics and is set in locations that make it seem like an ancestral fairytale.

The films deals with the mutilation that young women have to undergo, an ancient tradition that still has to be dealt with completely, and Sembène decides to portray the women of Africa, both old and young, at a crossroads between tradition and modernity. Sembène, with his highly politicized but ultimately benevolent and sincerely humane cinematic eye, gave a voice to the voiceless.

7. Woody Allen

The list of female leads in Woody Allen films (often acting alongside male characters who are somewhat similar to Allen in attitude, or alongside Allen himself) is endless.

Mia Farrow, Diane Keaton, Gena Rowlands, Drew Barrymore, Emma Stone, Scarlett Johansson, Barbara Hershey, Helen Hunt, Mariel Hemingway, Marion Cotillard, Cate Blanchett, Dianne Wiest, Ellen Page, Rachel McAdams, Samantha Morton, and Anjelica Huston are some of them.

Despite the criticism he received in his private life, Allen never ceased to treat women in his films with the complexity and the reverence of a man who is puzzled, amused, and enamored with femininity.

6. Mikio Naruse

Mikio Naruse is one of the most beloved Japanese directors and has been described as “a great director of women”. In “Late Chrysanthemums”, a film from 1954, he describes with great nuance a total of four female leads; one of his most neorealist efforts is instead “Every Night Dreams”, a film from 1933. In Naruse’s canon, there are four films that stand above the rest: “Repast”, “When a Woman Ascends the Stairs”, “The Sound of The Mountain”, and “Floating Clouds”.

Naruse is interested in women and their ordeals, which often have tragic consequences, but his characters are strong and determined. Other notable films of his endless canon are “Wife” “Husband and Wife”, “A Wife’s Heart”, “Apart from You”, “Mother”, and “Lightning”, among others.

Naruse is interested in women as an “otherness”, but he explores the theme through the classical style of the melodrama, without experimental sensibility, but great technical ability, as evident in the ending of the film “Yearning”. Anybody who ever complained about the lack of female leads should turn their eyes towards Japan, especially the cinematic age from the 30s to the 60s, and the films of Mikio Naruse.

5. Lars Von Trier

Here’s another director with a controversial relationship with women. Where do we start? Maybe we could begin with “Breaking the Waves”, in which Emily Watson undergoes all sorts of brutal punishments, both emotional and physical. it was made even more disturbing by the fact that she is the embodiment of innocence, and after all the punishment, she supposedly receives her reward in heaven (but probably doesn’t, it’s a von Trier film after all).

Maybe we could start with the hardcore scenes in “The Idiots”, the mistreatment of Bjork in the film “Dancer in the Dark”, in which she sings like a wounded swan before getting hanged and destroyed by the cruelty of the world (all these films are fittingly part of “The Golden Heart Trilogy”).

Maybe we could start with the failures of the leading women in “Dogville” and “Manderlay” and the way their communities reject them. Or perhaps we could start with the demonic nature of Kirsten Dunst’s character in “Melancholia” or the five-and-a-half hour sexual epic “Nymphomaniac”, with great performances by Stacy Martin and Charlotte Gainsbourg.

Surely though, we should end with “Antichrist”, where the apocalyptic confrontation between the sexes and the woman is seen as incomprehensible force, to be feared as a castrator and an adept of Satan’s church. Von Trier is confrontational, direct, a bit of a prankster sometimes, and a great filmmaker.

4. Alfred Hitchcock

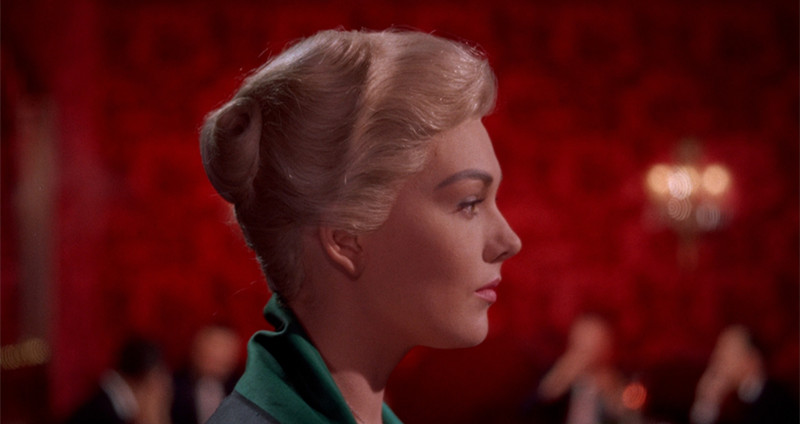

Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Blondes make the best victims, they’re like virgin snow that shows up bloody footprints.”But what is a Hitchcock blonde? It is an icy blonde, elegant, sophisticated, and with inscrutable beauty that is often the lead character in a Hitchcock film.

The celebrated director was obsessed with his female leads, and always subjected them to grueling shooting schedules and sequences in various films. He wasn’t exploiting their beauty, but he always made them the most compelling and psychologically developed characters of his films. The nature of Hitchcock’s obsession might be Freudian, but certainly the glacial look of his blondes added more mystery and a haunting atmosphere to his films.

The original Hitchcock blonde was Madeleine Carroll in “The 39 Steps” in 1935; after that, there was Ingrid Bergman, who starred in three Hitchcock films from the 40s, “Spellbound”, “Notorious” and “Under Capricorn”. “Spellbound” was one of the most surreal Hitchcock films, while “Notorious” is considered by many as his masterpiece, as Bergman acts next to another great star of the era, Cary Grant.

After Bergman, the new icy blonde was Grace Kelly, who was the most iconic of all because of her mixture of strength and cool elegance that perfectly epitomized the 50s and the Hitchcock style. Her most famous role was “Rear Window”.

After Kelly, Kim Novak was the new celebrated lead in Hitchcock’s classic “Vertigo”, where the director focused his cinematic eye even more obsessively on female nature and beauty. His last blondes were Eva Marie Saint, mostly famous for her role in “North by Northwest” alongside Cary Grant, and finally Tippi Hedren, who had to endure real physical harm during the shooting of “The Birds” to meet the expectations of the director. The female lead is a staple of the suspense genre, thanks in part to Hitchcock.

3. Max Ophuls

The technical wizardry of Max Ophuls becomes even more impressive when collocated in the age of filmmaking in which he was working. The long takes of the film of the film “Le Plaisir” seem to have inspired the much praised “Birdman” by Alejandro G. Inarritu, among many other films. To Ophuls, life was movement, ornament and beauty; it was almost inevitable for him to become a great director of women.

Ophuls made melodramas with noir inflections and a subtle psychotic undertone that is well concealed under the shiny surface of the film. In his earlier works, the tone was more influenced by the comedy of authors such as Lubitsch. His most decorative film was probably “Lola Montes”, about the life of a courtesan and a showgirl, told in almost acidly colorful style that has influences from “The Red Shoes”.

Then there’s “The Earrings of Madame De”, a an opulent and tragic melodrama, and there are some films that are connected to the tradition of musicals in the 30’s, for example the film “Divine”.

Ophuls set some of him most celebrated films in brothels, telling stories of chambermaids and prostitutes, and generally of the meeting between the spiritual and the physical pleasure, films such as “La Ronde” and “Le Plaisir”.

Ophuls has been an underrated filmmaker for awhile, but now he has finally reached the respect he merits, as his technical abilities and ornamental style always got in the way of critics appreciating the substance of his work, both artistic and social.

2. Jean-Luc Godard

Jean-Luc Godard made a number of films that focused on women in the 60s, such as “A Woman Is a Woman”, “Breathless”, “Masculin Feminin”, “Vivre sa Vie”, and “Contempt”, but continued with his fascination in the 80s with films like “Hail Mary”, all the way to his late period, “In Praise of Love” and “Goodbye to Language”.

When confronted with the problem of the representation of women advanced by Laura Mulvey, which argues that women are on screen to be looked at, Godard would respond with a Deleuzian response, with the idea that cinema, being a projected medium, the essence of which is movement, avoids fixity and solves the problem of representation through sensation.

To Godard, women are a moving sensation, in constant development, just like cinema; therefore women are the very essence of cinema, as our attention to their bodies is the actualization of physical metaphors, and the purest form of cinema.

Despite the methodical nature of Godard in relating to the women in his films, we can see, as we have notable examples in “Masculin Feminin” and “Contempt”, that women are the physical representation of plurality, constant movement and development, while men are often almost embarrassed in their unitary nature and fixity.

The infinite number of outfits that women wear in Godardian films from the 60s are also an homage to pop art and the age of reproduction. Godard is certainly, in his radical and volcanic nature, a perfect director of women.

1. Kenji Mizoguchi

“Osaka Elegy”, “Sisters of the Gion”, “Women of the Night”, “Streets of Shame”, “The Life of Oharu”, “Miss Oyu”, and “Ugetsu” are all films by Mizoguchi that are supremely socially aware and interested in the role of women in Japanese society. It is well known that Japan has had much discussion about the patriarchal structure of their society and how women are sexually frustrated and generally insecure, and face exploitative patterns (which is a fairly unique aspect in capitalist countries).

Enjo kosai is a phenomenon in Japanese culture in which a young girl will date an old man for a monetary reward. The attitudes toward fetishes, prostitution, and sexual habits and propaganda are also very unique in Japan.

“Streets of Shame” is concerned about the life of a sex worker (a major inspiration for Sion Sono’s film “Guilty of Romance”); “Ugetsu” introduces the concept of the ethereal femme fatale that will become popular in morality tales and horror films in Japanese cinema in the following years (from Kurosawa’s “Ran” to Kobayashi and Shindo’s films); “Women of the Night” sees one of the first great performances of famed Japanese actress Kinuyo Tanaka; “Sisters of the Gion” explores a geisha house in pre-war Japan; and “The Life of Oharu” explores the suffering of a woman in 17th century Japan to the hands of a patriarchal society, using a style so crude that it was accused of being exploitative.

The social components of Mizoguchi’s films tend to be much more politicized than Ozu’s films, which known for their delicacy and don’t have the melodramatic tendencies of Naruse’s films, but are essential to the country’s cinematic traditions and are an acute cross between Indian and Italian neorealism and the typical traditional cinema of Japan.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.