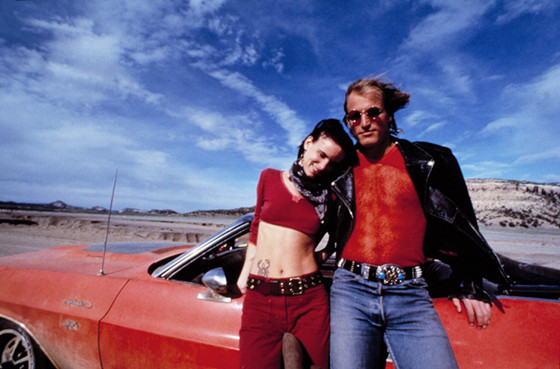

8. Natural Born Killers (Oliver Stone, 1994)

This pulp-like movie, which is delirious in its colors, scenography, photography, is expressionist oriented, and is nearer to Bergson’s idea of comical character than what it seems. This movie, thanks to Oliver Stone’s point of view, shows the necessity of the absence of the self-directed comedy.

Two lovers, Mickey and Mallory Knox (Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis), are also serial killers. Both of them are completely unconscious of their ridiculous characters, and they are conscious only of one thing: their love (and nothing else matters). Mickey and Mallory are exaggerated in every sense; they are burlesque, sometimes vainglorious, and the movie is always swinging between humor and irony.

At the end, television wants to show the story of those two crazy killers, but the laugh, on the contrary, is reflected toward society. “If there is visible craziness it mustn’t be other than a conceivable craziness with general spirit’s health, a normal craziness, we could call it. It exists a normal state of the spirit that imitates perfectly madness, where there are the same associations of ideas like in alienation, the same singular logic like in the fixed idea; this is the state of dream. If our theory is exact, it ought to be formulated in this way: comic absurdity is of the same nature of dreams.”

7. Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936)

“Attitudes, gestures, movements of human body are laughable in the same proportion that body let us think to a simple mechanism.” With this simple phrase, we can summarize the essence of “Modern Times”, where a worker, without using words, permits the spectator’s laugh.

What we notice at first sight is the deep mechanization of human soul; Charlie Chaplin shows us a form of alienation brought by industrialization, where human beings become machine-like, so they become ridiculous and laughable. This contrast is simply endless, already a myth, from men to their creations when man and machine collide.

In this movie, man is reduced to a machine; we can laugh, but we know we’re in front of an everyday truth. “A mechanical procedure overlapped to a living body: here is our starting point. From which point here comic derives? From the fact that living body hardens in a machine. The living body seems to us, therefore, should be perfect agility, the activity always awakening of a principle always active.”

6. Fantozzi (Luciano Salce, 1975)

This little masterpiece reminds us of a Bergson quote: “The comic is born when men gathered in a group direct their attention towards one of them, letting hush their sensibility and exercising only their intelligence.” Bergson believes that when we focus only on the body of a person and we see it every movement like an automaton, like a puppet, we can hardly resist laughing.

This movie is the story of a deskman completely impended by life, and with a humorous description of the officer’s lives, Luciano Salce has given us one of the best pictures of the Italian medium lifestyle in the 70s (but not too far in their general trait from nowadays).

Ugo Fantozzi (the protagonist), always overtopped by various directors, colleagues and various stereotyped and burlesque characters, confirms the Bergson’s idea of focus: we can see Fantozzi more like a real clown than a person. “The laugh, as straightforward as one might think, always hides an agreement secret thought, almost of complicity I might say, with other people that laughs, real or imaginary ones.”

5. La Città delle Donne aka City of Women (Federico Fellini, 1980)

In this movie, Fellini cast his ironic regard toward the feminist movement. While he is traveling, Snaporaz (Marcello Mastroianni) reaches a dream-like hotel where he has a feminist encounter.

What is particularly Bergsonian in this? “Behold, when a comic character follows his idea automatically, he ends to think, talk, act like dreaming. Hence dream is a severance. Rest in contact with things and men, seeing only what is and thinking only what is logic needs an uninterrupted strain of intellectual tension: common sense is this same strain, is work. But separating from things and anyway uniting together ideas is not than game or, better if you want, laziness. Comic absurdity gives us hence, at first sight, the impression of an ideas’ game. Our first movement is to associate to this game; this serve to let us relax from thought’s hardships…”

The main character always searches for sexual stimulus, where, respectful to female aggressiveness, he starts to search for a totally different kind of relationship, far from any idea of an independent feminist woman.

The Snaporaz dream notes Bergson’s definition of irony and humor previously quoted; the distinction between real and ideal vanishes and what remains is a dream of women, where man desires to abandon himself in an ideal woman’s embrace but this let us smile, because we know that this “women’s city” exists only in a dream (or in a nightmare).

4. Play it Again Sam (Herbert Ross, 1972)

“A situation is always comic when belongs at the same time to two series of events absolutely independents one each other, and when it could interpret itself every time in two senses completely different. We’re in front of quiproquo. – And the quiproquo is, in fact, a situation that show at the same time two different meanings: one usually possible, that actors gives, the other real, that public gives.” Woody Allen is a master at recreating this kind of comic situation, in particular through his linguistic ability.

Another kind of type of comic feature that he uses in an exceptional way is the use of metaphors. Here, the director presents, like in many other Allen’s comedies, a divorced man who tries to find a new woman. But every time, he wears a Bergsonian mask that hides, in different exaggerated and ironic ways, his true personality. This movie retrieves many ideas quoted by Bergson already quoted, but with one more useful characteristic: Woody Allen was able to put them all together in a masterfully ironic way.

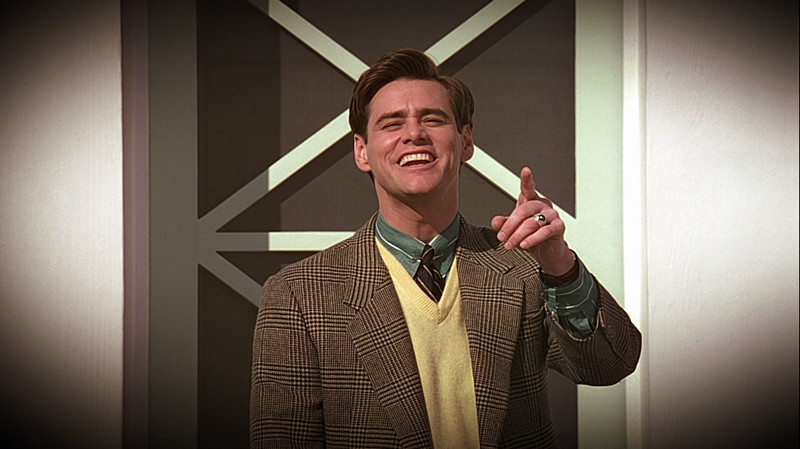

3. The Truman Show (Peter Weir, 1998)

In his books, Bergson described three types of comedy mechanical dispositions. “The Truman Show” reflects very well the second one: the puppet with twines. In this movie, a man was born only to star in a giant “Big Brother” show, constructing around him a massive television cast and set.

Truman (Jim Carrey) lets us think about the social register always manifested by the “laugh”, and in this situation its taste is absolutely bittersweet. The comic part of the film is only the first half; in the second half, we empathize with the protagonist, so our laugh vanishes.

With this movie we could rethink our laughing ideas, agreeing (or not) with Bergson, but to think about the role of sensibility in our favorite comedies. “Everything serious there is in life derives from our freedom. Feelings that we’ve maturated, passions that we’ve nourished, the actions we’ve deliberated, executed, at last what derives from us and it’s our and what gives to life its trend sometimes dramatic and generally grievous. What we need to transform all this in comedy? Just imagine that outward freedom overwrites a twines’ game and that we are on earth like the poet says – humbles marionettes whose ropes are in necessity’s hand. – Hence there are no real scenes, dramatic also, that fantasy cannot push unto comic with evocation of this simple image. There’s no step toward which is open a wider field.”

2. A comedia de Deus aka God’s Comedy (Joao Cesar Monteiro, 1995)

This movie is certainly related to a kind of absurd comedy, but at the same time is laughable. The plot is based on the story of the owner of an ice cream shop that tries to reach a sublime flavor while he collects female pubic hairs. Bergson describes in the second chapter of Le Rire a Jack-in-the-Box mechanism hidden in comedies.

A moral spring is always compressed while sometimes, in an explosion, there is a particular human behavior going so quickly that we cannot contain our laughter. “Reunite then two similar men in one, let this character hesitates between a frankness that stings and a courtesy that befools; this fight of two contrary feelings will not be comic yet, it will seems very serious if the two feelings arrives to fuse in their same contrariety, go together, create a complex mood, at last adopt a modus vivendi that simply gives the complex impression of life.”

The protagonist, Joao de Deus (interpreted by the director himself), is this kind of explosive personality where the spectator is unable to say when his comic potential will explode. Joao de Deus doesn’t want to change; he always remains rigid toward anyone, in particular toward his waitresses. Deus’ lifestyle creates a poetic contrast between the two souls of this exceptional movie, where every poetic glance could become ridiculous.

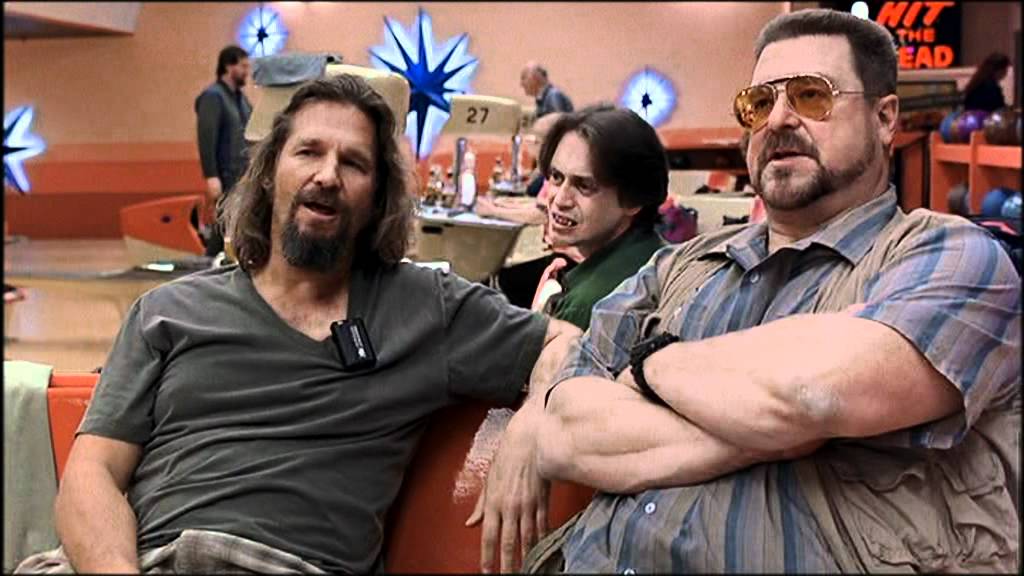

1. The Big Lebowski (Joel and Ethan Coen, 1999)

Incredibly, the story of The Dude (played by Jeff Bridges), well known in “The Big Lebowski”, follows a lot of Bergson’s suggestions on laughter. In particular, the French philosopher talks about a third comedy mechanism: the snowball effect. Starting from a small cause, a not so laughingly situation of homonyms, we end up with a giant effect, which is the entire series of the Dude’s adventures; the snowball rolling down a hill is growing larger and larger to a final devastating effect.

But this movie is also a collection of previously mentioned Bergson’s theories on masking, jack-in-the-box, mechanism, gestures and language tricks. “The rigid mechanism that we surprise, at any moment, intruder in the living continuity of human things has, for us, a very special interest, because it’s like a distraction of life. If events could always been connected to everything of their course, we cannot have coincidences, encounters, circular series: everything will untwine in a rectilinear guise. […] Laugh is the correction. Laugh is a social gesture that underlines and repress a special distraction of men and of events.”

This movie represents a forever-growing laughter that is impossible to stop, but this is not a laughter derived only from mechanical movements; the spectator has only the impression that The Dude is guided like a puppet.

The Dude, thanks to his exceptional charisma, is going through several absurdities (following a dope-dream-like logic) in a stoic straightforward way. We can imagine a bridge from Bergson’s laugh theory to a Zarathustra’s baby (quoting Nietzsche) where the laughter becomes conscious, so it becomes philosophical.

Note: Every citation in quotation marks is taken from: Henri Bergson, Il Riso, Laterza, Bari 1993

Author Bio: Luca Badaloni is studying his master’s degree in Philosophy. He believes that cinema is a perfect instrument for philosophical ideas and actually society needs critical thinking in several ways. He loves to write script, direct short movies but mostly, he loves reading.