For one of the most liveable and most advanced nations in the world, Australia has very rarely made a splash with its films, with most Australian recognition in the cinema down to the actors that make a name for themselves quickly before moving to America.

The likes of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, Chopper, and Animal Kingdom have been rare examples that ended up with attention and acclaim in the States and in Europe, but these films as listed below are all exceptional and even masterful pieces of work that can’t help but fall into obscurity.

They are not only entirely Australian productions, but are oozing with their Australian-isms that if they received more recognition, would put the county’s culture more on the map — hopefully this list can make a start on that.

1. Don’s Party (1976)

It’s not often you see the director’s name standing next the title of the film when it comes up in the opening credits, but when you see the screenwriter’s name there, it surely says something about the writing and dialogue of the film.

Mostly set in one house during the 1969 election, Don throws a party and invites all his friends and their partners to discuss politics – about forty minutes into the film (and after a few cases of beer), most political talk has completely stifled and instead we have relationship disputes, angered outbursts, fights over extra-marital affairs, all of which has been finely scribed by screenwriter David Williamson, who penned this as a stageplay in the early ‘70s.

With its filmic adaptation, many of the cast members stuck with their characters they’d played on stage, meaning the actors and writer had plenty of time to really give flesh and blood to their trying, yet flawed characters.

2. The Devil’s Playground (1976)

Not many filmmakers can make their self-financed directorial debut a religious experience, but Fred Schepisi’s The Devil’s Playground was very much that – according to the director, the film convinced many young teens to leave their own religious trappings, writing letters to the director and explaining their own experiences.

Although the central focus is on Tom, a 13 year old bed-wetting pupil at a monastery in Australia as he has his faith tested, we get plenty of insight into the religiously dominated lives of his class-mates as well as the Brothers, and it seems each Brother has a very unique view on the monastery and the regulations it enforces on themselves and the students.

This is an explorative film, technically and thematically reaching the heights of Ingmar Bergman’s own faith-charged films, though remove all references to religion and this film is still about the pressures of this prepubescent boy who is trying to overcome his shortcomings and find his way in the world whilst the institution he’s under enforces more troubles for him. That is something most people can relate to, making this a universally felt film.

3. The Last Wave (1977)

Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock is a true blue staple of Australian cinema, so it’s a bit of a shame that his follow-up is largely neglected, despite being even more mysteriously enigmatic. Amidst a nasty season of heavy rain, a lawyer must defend five Aboriginals in a ritualistic murder case, but he finds himself gradually absorbed by this community until it leads him to a literal underworld.

Like Picnic at Hanging Rock, this is something of a quasi-horror film, though really works better and more effectively than most actual horror films — it masterfully builds an uneasy form of suspense and doom through some very odd dream-like sequences that, through superb and tempered directing, only gradually reveal the context that they are in.

This is a haunting film not for aquaphobes out there, and its uneasy depiction of an imminent apocalypse will make you feel like you’re drowning, even long after the movie is over.

4. Newsfront (1978)

One of the great intimate epics of Australian cinema, this quintessential film of the Australian New Wave shows the history of the newsreel era in Australia, spanning the years from 1946 to 1955, entertainingly portraying the emerging modern-day Australian characteristics of the time whilst documenting the in-studio arguments and on-the-road adventures these dedicated filmmakers were a part of.

Segments of the film were filmed in black and white so they could be seamlessly interspersed with actual newsreel footage, best utilised in the Hunter Valley flood sequence which helped give this low-budget film more of an epic scope.

Within the context of the Red Scare at the time, our cameraman protagonist Len Maguire is against the xenophobia and claims that for Australia to truly be a democracy, differing political opinions are allowed to be presented, and he represents this ideology in his work ethic. There sure are a few tips and tricks here that the modern day media can learn from.

5. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978)

Although this was really one of the first Australian movies with a focus on Aboriginal characters, it ended up providing quite the punch in the mouth with its racially charged violence, making this a hard film to sell (and likely not one that would be made today).

The titular character, played brilliantly and instinctively by newcomer Tommy Lewis, is a young mixed race man raised by very Anglo-Saxon guardians who encourage him to become a part of white culture by getting a job, but by rejecting his Aboriginality. Despite Jimmie’s endearing enthusiasm to fit in, he is met with such hostility in all regards of his life, he “declares war” and takes revenge against those who disregarded him as less than human.

Fred Schepisi’s wonderfully filmed arthouse character study turns rather suddenly into a violent revenge film, leaving audiences stunned and speechless by its aggressive second half.

White Australia’s relations with the indigenous people has been extremely testing at best, and this film is a perfect reflection of the anger Aboriginals face at being judged less than their white counterparts, making this quite a disturbing, yet perhaps cathartic movie experience.

6. Stir (1980)

Australia has generated more than a handful of perhaps the most brutish and most hard-hitting films that would even make Sam Peckinpah go pale. One of the roughest and toughest is this prison film, written about the Bathurst riots (as well as the Attica riots) by a prison in-mate at the time.

Stir (like another particular prison movie on this list) is all about anger being built up until it finally explodes in an outburst of violence, depicted here as a group effort by all the prisoners.

The riot sequence, lasting the film’s final thirty minutes, shows utter destruction of the jail as the guards helplessly watch on with their rifles aimed from the outside.

The constant shouting, banging, and explosions that make up the soundtrack and the unrelenting brutality displayed in this sequence make it pure cinema, uncompromising until the film’s finale. Stir is a film so powerful, it’ll leave a scar on your soul and a bruise in your mind.

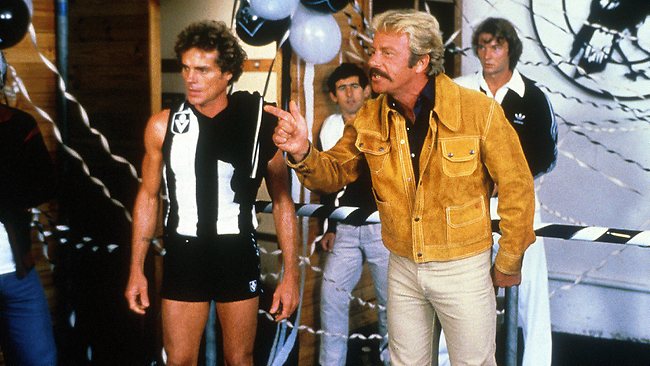

7. The Club (1980)

Director Bruce Beresford had a hell of a time in the first year of this decade, releasing two great films. Breaker Morant, an engaging court-room drama interspersed with explosive war scenes, became a much loved production from down under, and even ended up with an Oscar nomination and had Jack Thompson win the very first Best Supporting Actor award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Beresford then impressed everyone by having another film released so close to Breaker Morant, in many Australian cinemas both films were playing.

Talk about a double bill, though The Club is admittedly a more relaxed affair, dealing with the inner politics of the Australian Football League, not war, but it’s equally as engaging as it explores in a light-hearted and humorous manner the intricate dealings that go on behind closed conference doors of Australia’s favourite national sport.

Like an Australian version of Moneyball made in the early ‘80s, this is also a sharp and amusingly performed “sports” film, cynically acting as a scathing critique on how the sport had the fun sucked out of it due to privatisation.