7. Paris is Burning (Jennie Livingston, 1990)

“Paris is Burning” may be the most important documentary film in Queer cinema history. The film’s importance is so big than it even helped build the Queer theory; as one of her main studies, Judith Butler used the film as a main example in one of her books. The film is a study about the ball culture in New York and its members.

A strongly political film, it focuses on the minorities inside this already marginalized lifestyle. The black and Latino members of the scene are the main characters, and the film makes a beautiful contrast between the most serious and dramatic side (the poverty of the members, society exclusion, the AIDS menace) and the lighter part (the ball competitions and the love for dance). But everything is mixed in Livingston’s film.

The ball competitions are political as a comment on the government. And an AIDS discussion is as serious as the possible winner of the annual “Voguing” competition. Everything flows so naturally that at the end of the film you can only feel a desire to learn how to “vogue” correctly.

8. My Own Private Idaho (Gus Van Sant, 1991)

Gus Van Sant’s films are populated by characters living on the margins of society, and his films are a constant struggle between outsider characteristics or with fitting in. It works also as a metaphor for his films, which are always between mainstream codes and indie experimentation.

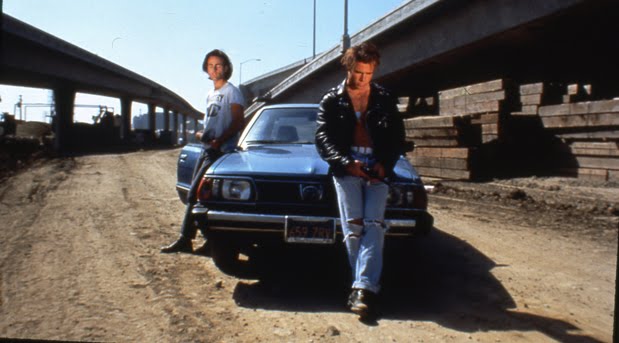

“My Own Private Idaho” belongs to the second group with an indie spirit, and was quickly placed as one of the iconic films of New Queer Cinema. With the definitive performance of River Phoenix and a stronger than usual Keanu Reeves, the film presents two hustlers in Portland trying to find a family for Phoenix’s character.

The film explores the repressed sexuality of their higher-level clients, and their different unsolved fetishes. Like in many queer films, gays are seen as outsiders interacting with society, and they are shown in the margins and in their interaction with the “accepted” people.

There is a scene where Reeves’ character starts to live a rich, heterosexual accepted lifestyle and “presents” again to society with a wife. There is a small take that shows one of his former clients and sex partners (portrayed by Udo Kier) looking from afar. The struggle mentioned between being an outsider or a part of society is over when Reeves’ character decides to leave his old life in the past.

9. Poison (Todd Haynes, 1991)

Before breaking into mainstream audiences or being recognized as an Oscar nominated director, Todd Haynes had a more experimental approach to filmmaking. “Poison” was his first feature film, and consisted of three unconnected stories with several different styles.

The only connection, explained by the director, was the presence of Jean Genet’s ideas all over the film. Jean Genet was a French writer known because of his rebellious lifestyle and beautiful writing. Haynes took his attitude to modern issues, asking what Genet would think about AIDS or Ronald Reagan’s government.

As seen in films like “Far From Heaven” (2002) or “Velvet Goldmine” (1998), Haynes is a constant genre-swapping director, and likes to play between tribute and parody. In “Poison” we have a fake television tabloid show about a kid who shot his father and fled the scene, a 1960s-like body horror film, and a romantic drama inside a prison. Aside from the first tale, the other two present different queer related issues.

The 60s horror parody works as a metaphor for how AIDS spread and how society behaves toward it. The prison drama shows a repressed love from one prisoner to another. This last tale caused controversy in conservative sectors for its homosexual sex scenes, and for an erect penis shot. This controversy tells about the difference shown in the 90s New Queer Cinema. This wasn’t about asking for tolerance, but was made to show these existing issues without any sense of shame.

10. The Living End (Gregg Araki, 1992)

“An irresponsible film by Gregg Araki” is the first credit and image we see within the first seconds of “The Living End”. Some seconds later, we see a character spray-painting “Fuck the World” on a wall. “The Living End” is a film full of angst.

Very far from an intellectual or theoretical hate, Araki’s film is filled with a more primitive anger. If the fellow films of this movement studied deeply what they were against, “The Living End” seemed to be the common-day feeling of the Queer American community after Reagan’s and the first Bush’s governments.

The film shows a hustler and a movie critic infected with AIDS on a road trip. Most of the elements of the road trip are there: danger on the road, conservative enemies, and an inside journey done at the same time. But some elements are a total innovation for the genre, with the direction of the trip as a completely irrelevant element, and with latent sexuality between the members released from the first minutes of the trip.

Araki’s film presents more sex scenes than the average film of the 90s film movement. Maybe it’s because of the low-budget spirit, or for the “spit on the face” attitude Araki has, but the film gives a lot of importance to sex for the couple. Sex as fun, as a desire impulsion, or as a love expression, the road to self-destruction made by the couple is a sex drive.

11. Strawberry and Chocolate (Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, 1993)

In most of these films, context plays a major role in their significance. Compared to their fellow 90s Queer films, “Strawberry and Chocolate” looks as though it takes one step back. The unapologetic attitude is not present; instead we have a classic acceptance plea. So, what makes “Strawberry and Chocolate” a worthy mention in Queer film history? Released by one of the most important Cuban filmmakers, the film is still seen as the symbol of homosexual aperture on Cuban territory.

The film describes the friendship between heterosexual communist David, and homosexual quasi-dissident Diego. Playing with different stereotypes, with Diego as the extravagant intellectual queer and David as the convinced and squared-mind militant, the film was an eye-opener for Cuban audiences. The light humor of the film and the importance of this director made Cuban audiences discuss homosexuality on the island, a slowly developed issue until that time.

12. The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephen Elliot, 1994)

“Priscilla” became a cult classic since the moment it was released, and it is very clear to point why it won its importance in Queer film history. One of the reasons that made “Priscilla” a special take on drag performance was its cast.

With Terence Stamp, Guy Pearce and Hugo Weaving as the lead characters, it was an uncommon experience for the audience to see these recognized actors in feminine roles. The use of macho actors made the film enjoy a wider audience, and at the same time questioned different gender ideas applied to a certain type of actor.

“Priscilla” also gives a big space to performance and drag queen shows. As Queer theory says, gender can be performed onstage, and this is on every stage where we can see the characters perform. With a collection of camp classics, the film goes on the road with the Village People, Gloria Gaynor, ABBA and CeCe Peniston. It is no longer about asking permission or tolerance, but about the glorious performance on stage.

13. Happy Together (Wong Kar Wai, 1997)

Wong Kar Wai once stated that he had no interest on labeling his film as a “gay film”. Like in many of his films, there was a romance, and as in those films the theme is the possibility and exploration of love. But there is more than one reason to consider “Happy Together” as an important film for Queer cinema.

Rules are different in a country where homosexuality became decriminalized in 1990. But even in this context, Kar Wai’s film presents a love where the biggest problems don’t come from society. Unlike American directors, the gay couple in “Happy Together” doesn’t seem to constantly struggle against it. The struggling is all about being able to understand each other.

It is important to say that it’s not that Kar Wai decides to forget about context, but his view on love is always about this mystical and mysterious experience. But there is news in the background about Den Xiaoping’s death, so there are still subtle political comments in the film. But at the end, “Happy Together” is about a love relationship, above all, and the process of learning and growing from it.