7. Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

George Tomasini was the perfect pairing for Hitchcock’s vision. As an editor, he loved to experiment with different techniques while maintaining a great respect for the narrative. His vision meshed with Hitch’s films, which tended to be narrative thrillers full of innovative and audacious editing.

Tomasini and Hitchcock were admirers of ideas in Soviet montage, but instead of using these ideas as a road to propaganda, they used them as a way to imprint psychology into the characters. The scene in “Psycho” when Marion (Janet Leigh) decides to park at the Bates Motel after stealing her boss’ money shows some of these techniques.

Instead of using heavy dialogue or exclusively through Leigh’s performance, Hitchcock focuses her facial expression and the more scared she gets, the faster the cuts become. The editing amplifies Leigh’s performance, and her scattered frame of mind is transposed onto the way the scene is shot and also, therefore, onto the way the audience experiences the scene. The audience doesn’t need any more explanation in order to understand Marion’s decision to park at a random motel.

The “shower scene,” perhaps the most iconic in Hitchcock’s long career, became an instant classic, terrorizing American audiences in their comfort zone. Eisenstein’s “Odessa’s steps” scene is probably the only other scene with editing has been analyzed as thoroughly as Hitchcock’s “shower scene.”

In the “shower scene,” Eisenstein’s montage of attractions was used in a totally new way, completely reinterpreting the idea. Tomasini worked with more than seventy camera setups in the scene, and synthesized them into a 3 minutes scene.

The horror of the scene, and why it felt cruder than any killing scene before, was all due to Tomasini’s ingenious editing. Actual stabbing is never shown, and yet the feeling of each wound couldn’t be more visceral. The effect is timeless.

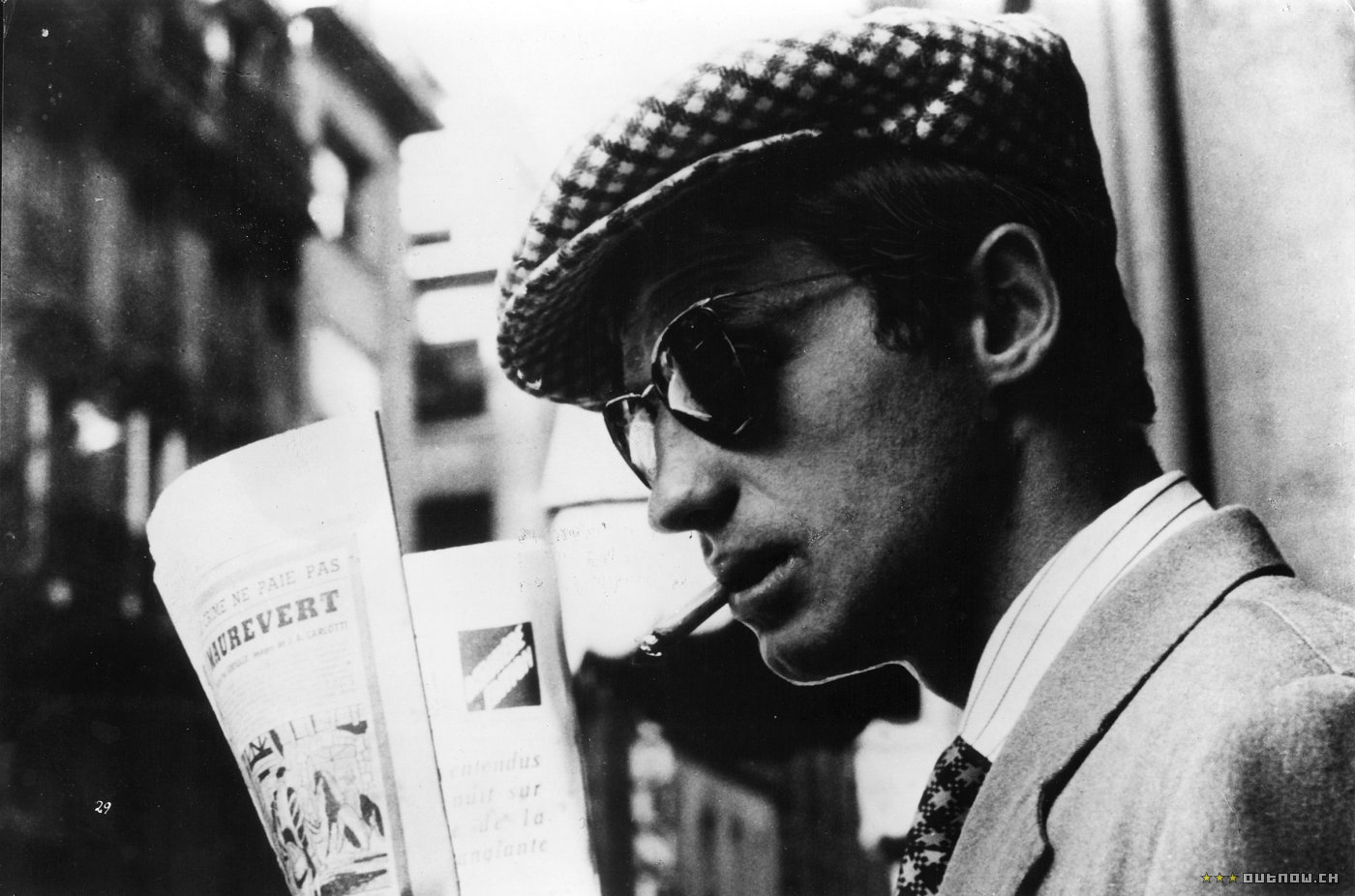

8. Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

It is no surprise to find so many 60’s films on this list. It was the decade when most of the modern filmmakers experimented and challenged the hegemony of the invisible cut. Probably the most influential of these films is Godard’s debut, “Breathless.” The film had a free-spirited form and a lot of self-referential elements. In thw Novelle vague movement, cinema wasn’t intended as an illusion, as 90 minutes to disconnect from the world.

Instead, these films constantly reminded the audience that they were watching a movie. “Breathless” used many methods to achieve this: unnatural acting, breaking the fourth wall, incoherent argument, etc. But Godard’s main strategy was the use of editing.

Before Godard, a jump cut was a mistake seen only on really old films due to problems in the restoration process, but he took it as a trademark for his film. In one shot, the character of Belmondo buys a newspaper, and in the next cut, he throws it away. The action in the middle is lost. Today the jump has become a normal resource in action movies; in “Breathless,” it was breaking the rules and remaking them.

9. Dog Star Man (film series) (Stan Brakhage, 1961-1964)

Among the many extreme ideas of montage during the 60’s, probably Brakhage’s application was the most extreme of all. Some films on this list applied overprint as a way to give an abstract tone to some scene; in Brakhage’s case, overprint became one of the key and most repeated codes on his series of short films, “Dog Star Man.” Brakhage believed that an untrained eye, uninfluenced by socialization, could be capable of seeing so much more.

In “Dog Star Man” there are a lot of image “clashes” like in Soviet cinema. Two unrelated images are juxtaposed to provoke a new one, but in the case of Brakhage it is not only an intellectual exercise. Unlike Eisenstein or Vertov, Brakhage does not pretend to send a particular message to the audience.

More than an intellectual view, this tiring series of images provokes a new feeling. Brakhage wanted to re-create through editing his idea of a primitive and innocent eye. The use of random images as a purely plastic exercise was his way to get this sensorial response. These are films about what he called “the act of seeing.”

10. La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

The (now not so) mysterious Chris Marker was always mixing his theoretical thought with film form. His films mixed academic writing and theory, free thinking and film, all in one form. His most “narrative” film, and most famous one, is a departure from this form, but not completely. His only truly fictional film (though Marker probably would disagree with the idea of a genuine work of fiction) consisted solely of still images, and was defined in the credits as a photo-novel instead of a film.

But there is something wrong too in pointing to “La Jetée” as a film made of still images, because this phrase describes every film. The brilliance of the film is how it makes you conscious of cinema as permanent illusion. Because in Marker’s film, deprived from the cinematic illusion of movement, we can still somehow see movement, and all the characters feel alive. The images aren’t displayed in the same form and duration. Marker cuts and creates tension, repeating images and making some of them longer. All the basic notions of film are contested through editing, without necessarily filming.

11. Jules and Jim (François Truffaut, 1962)

There are three French films of the early 60’s on this list, and to be honest, this is probably too few. “Jules and Jim” took some of the lessons on display in its fellow Novelle vague films, and made a quick free-spirited montage that reflected the feelings of its characters.

Jules and Jim are two young friends in love with the same woman. This confusion influences the camera style and editing, and it turns the film into a mix of techniques that were quite new in the 60’s. What Godard did with jump cuts, Truffaut did by reframing or freezing the picture. In Godard’s film the cut itself was what was so new and fresh, but Truffaut intervenes in the picture itself.

When Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) speaks in the middle of a party, the frame puts direct attention in her face, leaving the rest of the screen completely black. Watching “Jules and Jim,” these kinds of effects feel odd at first, but after the first half hour, the audience is immersed in Truffaut’s plastic translation of falling in love.

12. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966)

Editing styles are often not as noticeable as music or cinematography can be. There isn’t a certain stable way to cut dramas or comedies (at least on a first look). But in Spaghetti Westerns, there is a style of editing that became so influential that it is recognizable in hundreds of later films. In a Spaghetti Western parody, there are several identifiable tropes: cuts between different close-ups, middle shots of the same characters staring each other, several shots of identical length, and quick editing to end a scene and release the tension.

This formula comes from the classic final scene of Sergio Leone’s most famous work, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” Mathematics has always been one of the most important things to take into account while editing, and the precision of it in this scene jumps to a higher level.

To imagine the scene shot differently—with wider shots, for example, and without the intercut close-ups of snarling faces and parallel bodies—is to see how obvious and fake such an approach would be. But as Leone shot it, this over-the-top dramatic moment looks coherent and builds tension enough to makes us believe in this war of facial expressions that precedes the final draw and shootout.

This is probably the greatest scene, but this precise use of math is all over the film. The cuts from wide and open shots to extreme close-ups showed how any element of film language could be put next to the other if it is done right.

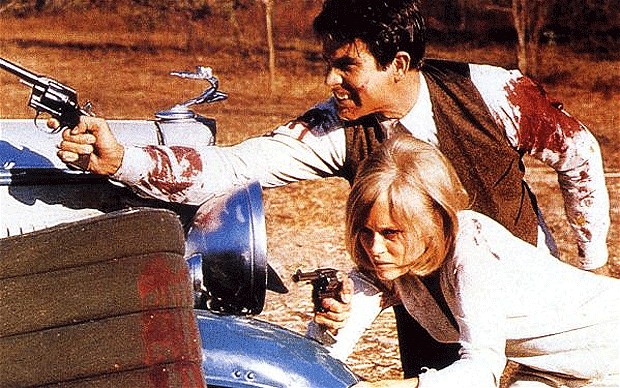

13. Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

“Bonnie and Clyde” holds it place in cinema history as one of the most important, if not the founding film, of the new American cinema. The movement started an interesting mix between a strict Hollywood tradition and different tricks coming from European and Asian films.

Arthur Penn represents this idea, releasing entertaining and popular films with a subtle acquaintance with the ideas of Novelle vague and Akira Kurosawa. His main editor, Dede Allen, applied different tricks he’d seen in French films, but instead of trying them as an intellectual exercise, they were intended as a dramatic element that made the film more exciting.

The jump cut or the staccato-like editing applied as an experiment by Novelle vague was used as a way to bring adrenaline to the shooting scenes in “Bonnie and Clyde”. Subtly, the American filmmakers started to mix all these elements and make them more familiar to a wider audience.

The final scene of the film is the main example of this. The classic climax is there, building tension with every shot, but at the final moment we have over 50 cuts in only a few seconds. Something that could look too experimental for its time was received as the best part of the film. We still have a classic “invisible” montage, but with some subverted moments, enough of them to change American cinema forever.