Among cinephiles, the imploration “You’ve GOT to see this movie in the theater!” is far beyond cliché at this point. We all get excited when we leave the local cinema feeling changed by the experience.

It’s a throwback to our cave dwelling days, when community groups would gather for shelter and exchange exaggerated tales which imparted upon us wonder and reflection.

This is one of the original charms of the early movie theater experience. What once was seen through a slot in Nickelodeon players was now shared in grand palaces the audience could spend a whole day in, sitting through short subjects, a stage show, and the feature presentation.

Although the modern-day film screening event has been diminished from its Golden Age of fanfare, it’s nevertheless an energizing spectacle. While in theory all films are made to be experienced on a large screen, it’s a relatively small number of filmmakers who consciously employ that setting as part of how the film itself plays.

Below is a list of 20 of the finest examples of such works, from almost every age of cinema, across a spectrum of genres. Each of these films play to a different strength in big-screen cinematics, and the experiences can vary wildly.

The art house film, for example, will dig deeper into visual language while perhaps the adventure movie uses editing and wide shots to impart a sense of audience involvement lost on a TV.

In any case, these films have proven themselves to have had bestowed upon them by their creators a very conscious sense of their own size as seen in the dark, shared space audiences go to witness a special kind of light.

1. Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Watch a man lose himself in the desert. David Lean’s biography of the infamous British soldier helping forge a new Middle East in the early 20th century is a study in the human journey of self-discovery and utter loss.

The sweeping sands and unrelenting sun appear as the protagonist’s quest for purity among the blood-soaked game of empire and tribalism.

The audience is placed into the disorienting desolation as Lawrence tries to “become Arab” and find belonging in a land and culture completely other than his upbringing.

The viewer is attached to his relentless march away from who he doesn’t want to be, right into who he has always feared he was.

The grand scope of the film’s many scenes in the wide open wilds of Arabia compliment beautifully the moments when the main character is just as lost within grueling bureaucracies or even at a lavish officer’s club where he attempts to return again to “being British.”

Watch a man chase fame and prestige even as he tries to be as ethereal as a grain of sand in the desert.

Lean expresses this against an always-dwarfing backdrop in which the audience, too, loses all bearings on the morality of Lawrence’s path. It’s a grand stage which is simply not felt on the small screen scale.

2. Star Wars (1977)

While in some ways, this choice might seem obvious and banal, one doesn’t often hear the “why” behind the cinematics of Star Wars which demands a large screen.

Many will mention the revolutionary sound design, as well as how the filmmakers had theaters configured for the surround experience. But what George Lucas really does here is put us in that rare Goldilocks zone of just enough action, just enough contemplation.

Yes, there’s wonderfully choreographed spaceship fights and light sabre duels, but there’s also the many quiet moments set against a sky with two suns or maybe crammed into a clunky freight vessel.

Whether it’s the sets, the models or the expansive landscapes, Star Wars made sure the settings were big on the screen and the camera gave audience time to digest the surroundings.

It gives the audience a sense of presence in Lucas’ finely-honed universe, and gives it a feeling of utter smallness.

This balance between thrilling escapism and brilliant composition makes the film draw viewers in almost with its own gravity.

This is best experienced in a large theater, surrounded by the ebb and flows of an equally engaged audience.

George Lucas should really allow us to have more opportunities to screen this gem as it was when it was first released.

3. Modern Times (1936)

To pick just one Chaplin film for inclusion here is hard. Every one of Charlie’s features has big screen virtues made by a virtuoso of the early age of Big Films. But Modern Times gets pushed to the front of the line.

This tour de force of comedic timing, impeccable staging and brilliant visual choreography was made for the industrial age and uses the relatively new form of film to show what it’s talking about.

In the famous scene where Charlie gets caught up in the mechanical works, he was well aware that he was emulating the threading of a film camera.

Charlie wanted to put the audience inside of the machine. And one cannot feel like a cog if the screen is a lot smaller than the viewer is.

Then there’s scenes like Chaplin’s spontaneous participation in a socialism march. This has the effect of making the whole theater feel like fish in the tide.

The entirety of the movie portrays modern living as far too unwieldly to navigate. And it’s all done in such hilariously funny ways.

Thank god it’s so funny or else the feeling of helplessness could become overwhelming. This one makes the repertoire list often in major cities, seek it out and enjoy.

4. Project A (1983)

In 1983, the young Hong Kong Kung-Fu action star Jackie Chan was given the opportunity to direct one of his own films. And he made it count.

Using the choreography of elaborate fight scenes as a guide, Chan constructed a series of acrobatic montages that meld Silent Film Era slapstick sensibilities with deadly serious martial arts practices.

Every single shot is blocked expertly, filling space with eye-popping stunts and physical conflict ballet which turns the very active camera into as much of a participant as the performers risking life and limb for our amusement.

And even more impressively, Chan adds humor to even the most serious of moments. He’s stated often that Harold Lloyd is his hero and it shows, down to the marquee gag involving a clock tower which Jackie lifts from the classic Safety Last.

The film is shot in the very wide Technovision’s 2.35:1 aspect ratio which none of the American home release versions properly reproduce (and that AWFUL dubbing).

All of the space is conspicuously used by Chan to great effect, often with many things happening on the screen at once.

There is no way to fully absorb the gloriously orchestrated chaos on a small screen, and certainly not in a pan-and-scan copy. Retrospectives of this era of the genre will often include a screening – not to be missed.

5. Faces (1968)

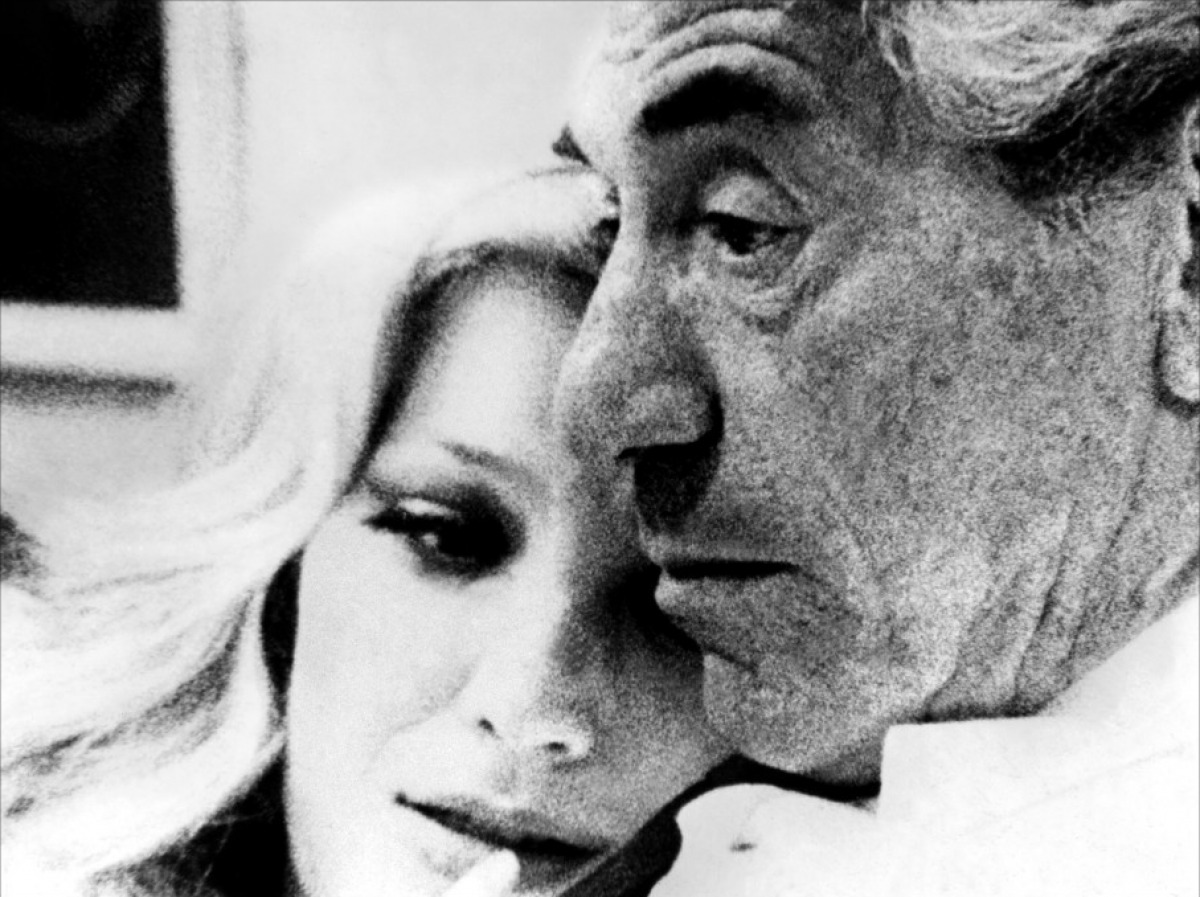

Few directors have mastered the art of making audiences incredibly uncomfortable quite the way John Cassavettes did.

Known for gruelingly long takes, with framing which firmly imposes the viewer into sharing space with the characters on screen, Faces marks possibly his most confining effort.

For over two hours, we must uncomfortably reflect on the familiar human failings we have all had to confront at one time or another.

You don’t have to share the lives of the hooker or business executive in the film – you’re in the room. You can’t escape. And even if you’re identifying with the alpha male in the scene, you know how small he really feels inside, too.

When the literal faces are projected large on the screen, it’s as if the audience is pressing their own faces up against a giant mirror. The effect is disorienting at first, and then painfully recognizable.

Of course, this one is watchable on the TV screen, but the effect is lost when you realize how even the negative space in the shots seem oppressive.

A masterpiece that repertoire hunters should be able to find with some regularity. Presenters may want to lock the theater doors to prevent the audience from running away from itself.

6. Serene Velocity (1970)

Ernie Gehr made this breakthrough experimental short while teaching alongside fellow Avant Gard master Ken Jacobs at New York’s Binghamton University.

The 23-minute, non-narrative silent film is a triumph of the purest art of cinematic editing. Taking a series of seemingly mundane shots in a seemingly mundane setting, free of characters or plot, Serene Velocity turns the forced tone upside down.

The climactic scene at the end is nothing more than a series of shots of a hallway, taken from the same perspective at different focal lengths. But the way Gehr cuts the shots together turns the ordinary corridor into an endless fall into a bottomless abyss – the stuff seizures are made of.

It’s a brilliant, frenetic meditation on what film can really do, once its stripped down to its most basic form. Needless to say, the mesmerizing effect of Serene Velocity is greatly diminished on the small screen.

The best place to catch it is probably in a film school class. But The Museum of Modern Art in New York City has preserved it, and it can be sporadically found on the experimental art circuit.