7. The Road Warrior aka Mad Max 2 (1981)

Forget the overhyped Fury Road – this is the film that is truly George Miller’s masterpiece. Another wide screen wonder (2.35:1), it’s easily the most artistic form of the car chase genre you will ever see.

Cinematically, Miller transforms the red Australian desert into a character unto itself rather than a mere prop. There’s a visual motif of thirst constantly reinforced with subtle actions, clever makeup and other details easily lost on the small screen.

The hero, played by Mel Gibson, is remarkably understated – he has likely less than 15 lines in the whole movie. But body language, facial expressions and metaphoric inserts are used to great power with great economy.

This is in stark contrast to the bombastic automobile battles, which are brilliantly choreographed. Miller eases us from one pacing to another effortlessly, allowing character arcs to grow quietly and organically.

He uses big skies, long shots of roads to nowhere and static overviews of vast spaces to take us by the eyes from fine dramatic acting to the explosive grinding gear wars on the deadly highways.

While the Blu-Ray is a fine transfer, finding a nice 70mm print to screen should be a quest for cinephiles.

8. Ran (1985)

If you’ve ever seen Akira Kurosawa’s storyboards for this film, you will understand what he was really trying to do: create a cinematic form of painting.

Drawn by a story idea very similar to Shakespeare’s King Lear, Ran is an epic tale of war, royal intrigue, betrayal and human frailty.

Using the environmental visual language of feudal Japan, Kurosawa stages tangled dramatic scenarios on grand scales as well as in painfully intimate settings.

Every single shot is an individual pastiche, assembled almost as if the entirety of the film was a sequential art exhibit that just happened to move and talk and breathe. But don’t believe for a moment all this gets too abstract to soak in.

Ran is the height of dramatic storytelling, a gut-wrenching journey into arrogance, regret and decline. Kurosawa famously used his three-camera method to capture some of the more impressive scenes, including the burning down of an imperial castle.

On the big screen, the audience becomes another of fate’s lavish chess pieces, being moved in and out of events at once grandiose and all too familiar.

Catching 70mm prints of this treasure may be tough, but 35mm versions tend to circulate with some frequency.

9. Intolerance (1916)

D.W. Griffith was indisputably one of the founders of the modern feature film.

Not only did he invent some of the most basic editing techniques routinely used in narrative films (like intercutting), he also gave birth to the first full-blown, large scale Hollywood spectacle.

The famous sets include the infamous recreation of Babylon – a full scale scenario meant to fully display every bit of excess to the doomed biblical city.

The film brilliantly follows four epic tales – 3 from history and one contemporary – interweaving them masterfully to express a message of hope and love among humanity’s destructive quest for vanity.

Truly a landmark in the study of film, it’s as much an education as an experience. On the big screen, watching Griffith foster a new language of cinema becomes more pronounced: history is shown as being far larger than any of us, yet it is only our own individual experiences that make any of it matter.

The film uses scale within scale to express this, which can only be deeply felt in a theater full of fellow human beings.

A very common entry in many festivals, college screenings and repertoire theaters, anyone serious about film is greatly urged to seek this one out.

10. Pacific Rim (2013)

One of the most natural genres to lend itself to the large screen is the Giant Monster movie, aka Kaiju (Japanese for “strange beast”).

After all, this is about creatures several stories high stomping on humans and their cities like they were ants and anthills.

While classics like King Kong (1933) and Godzilla (1954) are also must-sees for the big screen, Pacific Rim stands out because lifelong Kaiju fan Guillermo del Toro really pulled out all the stops to polish every edge of the gargantuan conflicts down to the smallest details.

Forget the “human” story – this is all about watching giant robots fighting giant monsters. Those scenes were choreographed and shot to make us all feel like the bugs we thoughtlessly stomp on every day as we walk.

The depth and intimacy del Toro treats those sequences with brings such fantastical scenes closer to home than anything before or since.

One scene in particular pits a hellish beast 30 stories high against a lost child in such a terrifying and personal way, you can almost forget it’s a popcorn movie.

With clever use of perspective and minimizing the number of cuts in these scenes, the director puts us in the impossible position of being helpless in a “size matters” world. del Toro also employs some of the smartest use of modern 3-D techniques to enhance this effect.

Large screen viewings are essential for this one. It’s hard to feel like an ant next to a television.

11. Wings of Desire (1987)

Win Wenders’ spiritual meditation of angels struggling with what it means to be human uses a filmic language at once stark and subtle.

The main core of the narrative is what it means to be aloof from human concerns and then to jarringly become entangled with them.

The film is black and white when told from the point of view of the angels, whose only purpose seems to be to watch all of our lives and record what has happened.

This means everything – triumphs, joy, despair, hopelessness and a great deal of mediocrity. But when we move into the human perspective, the film becomes color.

It is but one of the many walls the film throws upon the audience to reinforce the idea of separation.

It’s no mistake that the backdrop is Cold War-era Berlin – the original German title is actually Wings Over Berlin – and its imposing wall separating the communist zone from the free allied zone.

The film presents walls between the earthly and the eternal, between bravery and fear, between detachment and love.

Ultimately, the greatest wall the director erects is the one between film and viewer, and just as it happens on screen, those roles get reversed. When this happens on the big screen, it becomes one of the most transformative experiences in cinema.

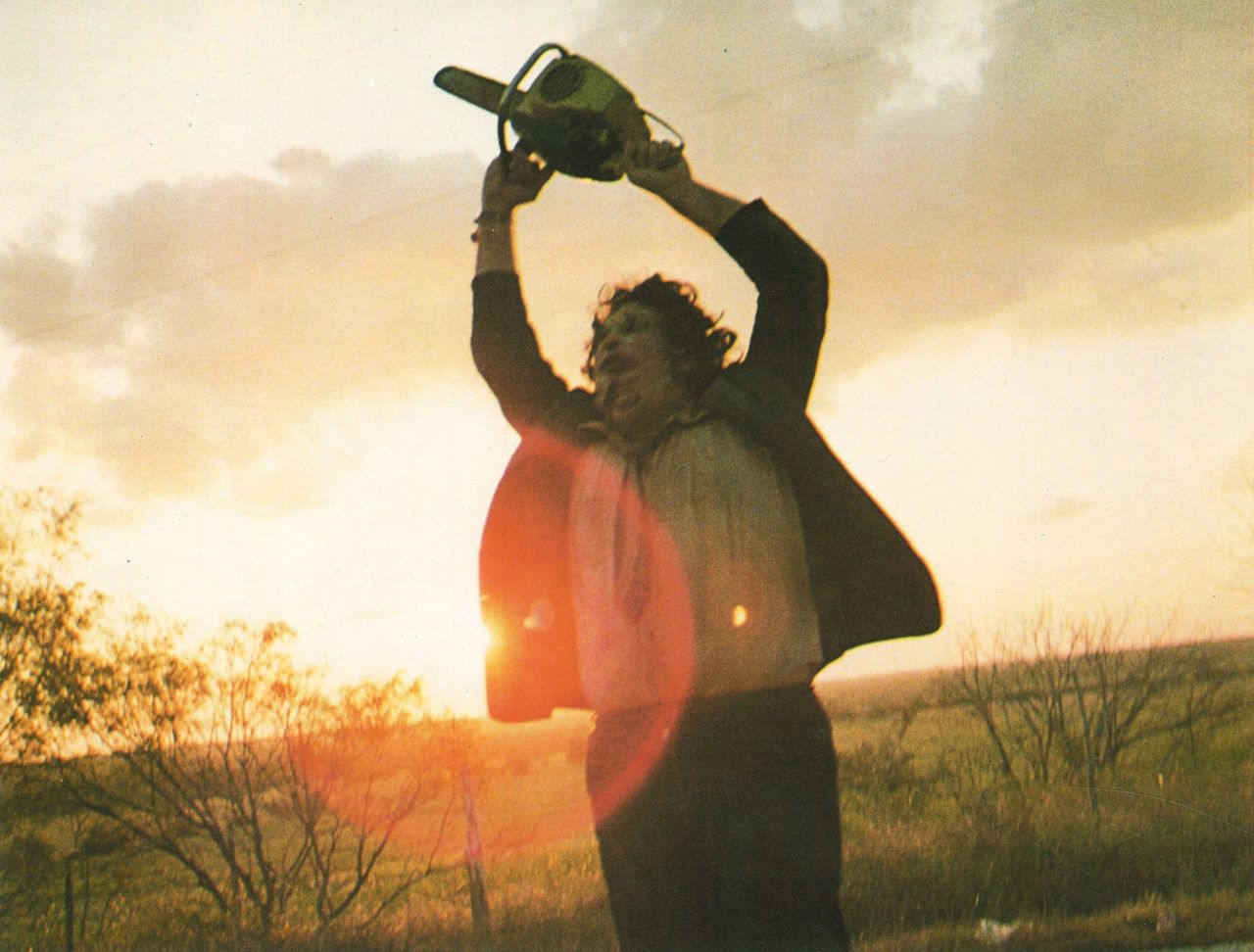

12. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

It’s an odd fact that one of the most notorious horror films in the history of cinema also happens to have an astoundingly small amount of blood.

Not only that, the worst of the violence happens out of frame. We don’t see guts spilled, we don’t see limbs dismembered. Instead, director Tobe Hooper harrows the audience with an incredibly claustrophobic experience, an irony that in a land of big, empty spaces, the Texas heat itself seems to squeeze people indoors and into madness.

The result is a film which can count the sun as a central character, which from the title sequence on, oppressively drives the macabre events in the film.

The transformation of free-running youth to the role of corralled livestock happens almost quietly at times. At the climax, viewers are caged along with a victim in a long scene which feels like it might be a vision from hell.

The disturbing interiors follow a powerful production design adorned with faux-primitive set dressing in what could otherwise be a normal dining room.

All of this is accompanied by a soundtrack which is more akin to sound design, like echoes in the realm of Hades.

On the big screen, the audience in literally trapped in an opera of insanity, torture and survival-level existence.

For fans of the genre, the film should be counted among the best horror films of all time. Get scared in a big way in the theater.

13. Spirited Away (2001)

Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli has produced some of the greatest animation ever made, all of which are best enjoyed on large screens. But Spirited Away has a richness of tones and textures which do something special to an audience – visually as well as in the way it plays out in the story.

The film follows a little girl on a family outing in modern-day Japan. Suddenly, the world before us morphs from ordinary reality to something wholly metaphysical.

Slipping through the ethereal seams of dimensions into a world of magic, witches and supernatural beings, hazy borders give way to a more metaphorical universe.

This happens in transitions of color palette, paint textures and ever-transforming characters, from humans to beasts and from good to evil.

Deceivingly disguised as a children’s film, there may be no better example of animation materializing such a richly deep place to explore, or that uses fantasy tropes so effectively in visual storytelling.

Ultimately, the tale of the child’s discovery of the esoteric reflects back upon the “real world,” where we average humans are equally as apt to impact our reality to grotesque effect.

This is a densely packed world, full of little details that speak of this strange land in quiet ways. One could watch this movie many times and see new nods to the state of the tale, and the confusion between its universe and our own.