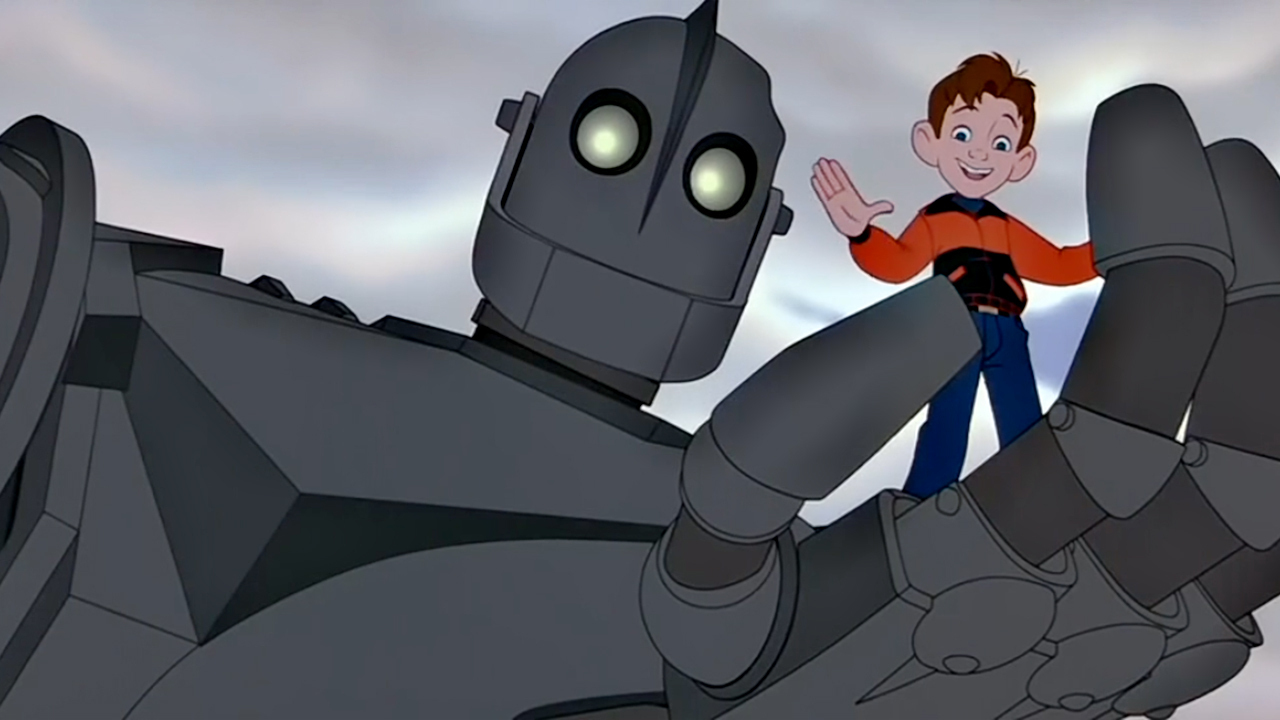

14. Iron Giant (1999)

This entry from animation great Brad Bird proves that size doesn’t matter when it comes to having a big heart. It’s a simple sci-fi story: giant robot with amnesia falls from outer space into small-town America; young boy finds and befriends it.

An homage to both the Disney features that came before it, and the classic era of the B-Movie (the film is actually set in the communist-obsessed, H-bomb fearing 1950’s), Iron Giant uses an organic juxtaposition between long views and down-to-earth intimacy to explore the coming-of-age choices the souls of both the tweener protagonist and damaged extraterrestrial machine.

Being equally sentient and empathic, the film explores motifs in contrast: large and small, hard and soft, light and dark, caring and destructive.

This is seamed beautifully between the visual language and dramatic storytelling which unfolds in the course of the film.

Naturally, it also has all the humor and charm of classic Disney, with hilarious fast-cut montages, exaggerated facial gestures and all the rest.

Utterly charming, it’s telling of contrasts loses much on the small screen. Such fluctuations don’t have the same impact and the experience becomes nothing much more than just a really good animated feature. Which is fine, but misses the full potential of the work.

15. The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

What we have here is an example of filmic poetry, about a real-life poet, expressed poetically.

Soviet-Era director Sergei Parajanov crafted this biography of Sayat-Nova, an 18th century poet from his native Armenia, using a wholly unique form of cinematic language.

There’s very little dialogue here. Most of the sounds are non-diegetic, using song, music and sound effects complimenting mood rather than driving story.

In fact, despite the sequence of events being carded in chapters reminiscent of the silent film era, there isn’t a hardcore narrative for the viewer to hold on to.

Instead, the montage is dictated by surging color transitions, design relations and iconoclastic constructions which has rightly become the subject of endless professorial reflection.

But grasping all the “meaning” doesn’t matter here. Parajanov has created a ballet of imagery that explains itself in ineffable visceral communication infused with a power to penetrate past the rational mind.

Streams of blood or flowing bright textiles become a dramaturgy of colors, the audience as a canvas.

The big screen allows immersion into this culture of hues and tones, leaving room for the background details and their unbreakable codes. On small screens, the muted effect breeds more confusion than exhilaration.

16. The Cremaster Cycle (1994-2002)

More a multi-media art exhibit that a single film, the core of artist Matthew Barney’s magnum opus are five feature films which make up the foundation of the work.

The full oeuvre includes sculptures, drawings and more, but the films are the primary transmitters of the oblique visual language of the overall piece.

Simply titled The Cremaster Cycle I-V, the films vary in length and obtuseness. The main cinematic language goes to great lengths to express life, birth and death, structural change, reformation and all of the natural and manufactured construction and deconstruction which rules the cycles of the universe.

I know that sounds heady, and really, there’s much more to it than all that. Largely non-narrative, icons are freely remade into their opposites – like say, the art deco majesty of the Chrysler Building becoming a place that crushes steel into featureless blocks of metal.

The iterations of these themes ebb and flow throughout the series, sometimes literally making up into down, causing the audience to leave with a very confused sense of the definitions of our reality.

This is probably the most esoteric film(s) on this list and together the films amount to 398 minutes. That’s over six and a half hours. So be warned: many critics consider this work genius while many others see it as self-indulgent junk. And the only way to watch it is on a screen.

The director refuses to release the films to any form of home viewing, except for 20 DVD’s which sold as art pieces to the tune of $100,000 for each set. If you can find screenings at your nearest art museum and love to be challenged cinematically, you are urged to attend.

17. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Every one of cinematic master Andre Tarkovsky’s seven feature films should be seen any way they can and most especially in a movie theater.

Always, this director thinks in very big, contemplative scenes thick with long takes and selective in editing. Andrei Rublev hits a stride in Tarkovsky’s signature style early in his career (this was his 2nd feature).

Here perhaps the effort was more subconscious, as it seems to permeate more levels of perception than his other works.

At once, this biographical tale of the eponymous 15th century Russian iconoclast painter serves as a meditation on the meaning of freedom, a critique of oppressive cultures (like the Soviet Union, where Tarkovsky made his films), and an expression of the director’s own inner conflict understanding his muse and motivations.

Andrei Rublev’s mise-en-scène is carefully crafted to give audience long ganders into the powerful illusions we have about liberty and tyranny.

He gives audience the time and space needed to feel these basic conflicts we all face: a scary ride on an air balloon that keeps gravity’s pull in view; a backwoods bacchanal ritual ends up reversing Christian morality when the pagans tie an intruder to a cross; a bell-maker commissioned for a new church lords around an army of craftsmen while a lack of confidence eats away at him.

These are big scenes meant to reflect intimate struggles against the raw power of nature and human grandiosity. On a big screen, the imposing blocking becomes larger than life, drawing the viewer into the larger forces which make us who we really are.

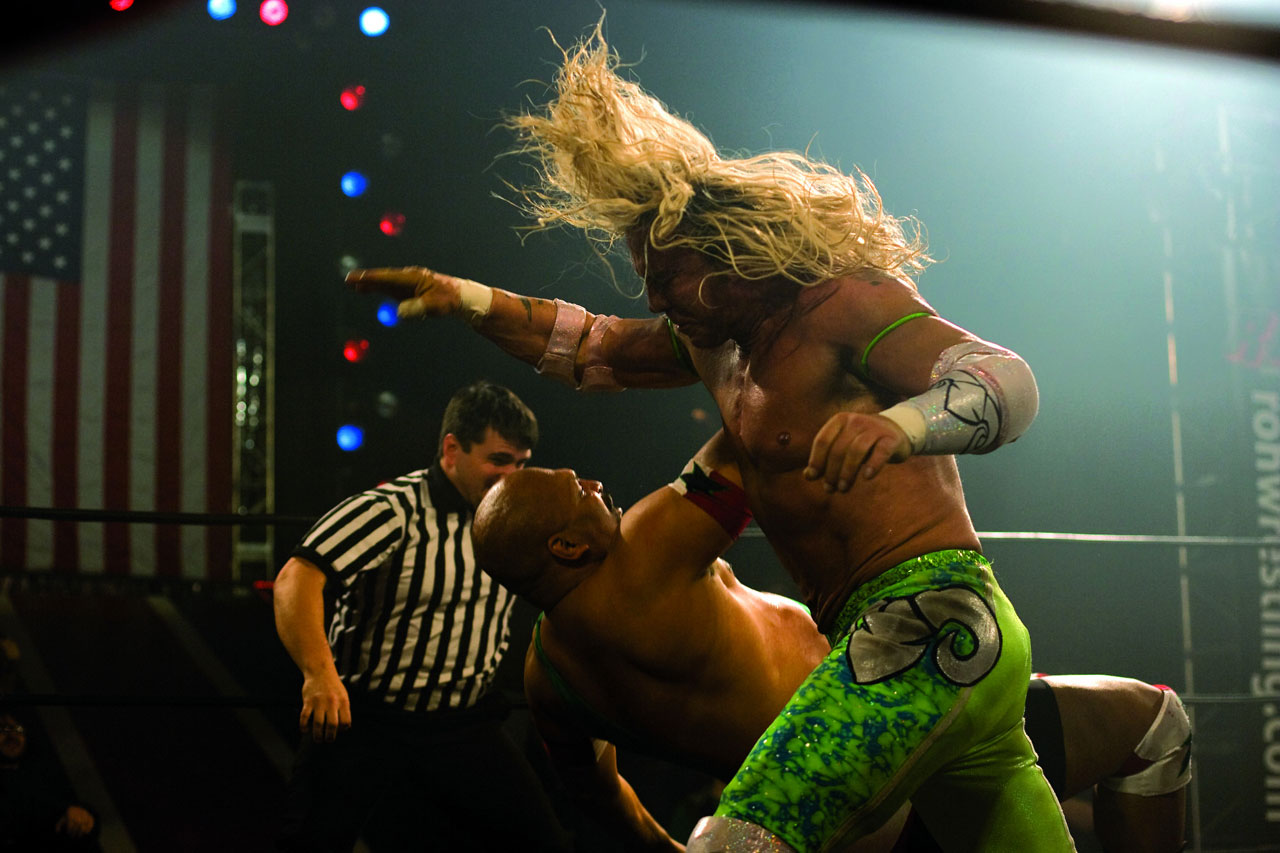

18. The Wrestler (2008)

Darren Aronofsky delivers a cinematic language of internal tension with a subdued montage straining against an overly animated protagonist who is wearing himself down to nothing.

The film follows the title athlete, an aging and ailing figure stuck in small-time celebrity, trying to atone for poor life choices with a comeback – both professional and personal.

With his loved ones short on forgiveness, living in a body beaten almost to death, time becomes the wrestler’s greatest opponent. Just as he is finding maturity, mortality threatens to rob him of redemption.

The director uses very understated camera and editing to achieve these feelings in filmic language. In an art form notoriously over-reliant on angle/reverse angle shots, Aronofsky visually puts the audience in the wrestler’s position – constantly wrestling against everything in his life.

The ripples of violence, sexual misadventure and substance abuse find an uneasy yet subtle swaying of the film’s frames, often blocked into corners, leaving the unsettling sensation of inevitability.

This film is not for the seasick, but it does strengthen the spirit by knocking it around like a hapless fighter. The theatre experience often finds the audience feeling as if everything outside of the screen is getting dizzy rather than the shots themselves.

19. The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

An almost-forgotten gem of 60’s Polish Cinema, director Wojciech Has wove perhaps the greatest story-within-a-story film ever made.

Adapted from an early 19th century novel, the tale starts off simply: two opposing soldiers in the Napoleonic wars discover a hidden manuscript in an abandoned inn.

Both are compelled to hear the story within, sending the characters and audience into a series of mystical yarns in surreal settings. But it’s not just one story – it’s many tales intertwined between other tales being told within yet more tales. The dizzying plot twists with gypsies, piles of skulls, and cabalistic gurus are hard to catch in just one viewing.

But the cinematic form employed is mesmerizing in its own right, settling the audience in a constant state of transformative nebulousness against a backdrop of dark magic and deep fears.

One feels eventually as though they are trapped in the belly of some unknowable beast, divorced from expectation and salvation. Part horror movie, part magical adventure, part meditation on the shifting foundations of reality, the story coils back inside of itself to a firm finality viewers may have forgotten was possible.

The constant feeling of being lost in a world beyond comprehension is at once terrifying and entrancing.

Caught in a large screening room, the dark effect becomes one of those rare times where the viewer really forgets where they are, and leaving the theater becomes as much of a shock as any other transition the film itself presents.

20. Playtime (1967)

Jacques Tati’s magnum opus of the Monsieur Hulot series, Playtime truly is, as Francois Truffaut remarked, “a movie from another planet.”

Using a series of casually associated vignettes playing loosely at being a narrative – which nevertheless is certainly linear – Tati hilariously takes us into modern humanity’s endless struggle to reconcile a more organic way of life with an imposing manufactured structure which makes meaningful personal contact so hard to come by.

Watching Tati’s alter ego Hulot navigating through office buildings, busy streets, modern television viewing and excessive materialistic pursuits, viewers end up laughing at the world they themselves are living in it.

The absurdity of sterile labyrinthine constructions, meaningless bureaucracies and the deliverance of discovering that honest travelers can still unearth the “real” world below, is framed against a stunningly designed set.

The “Tativille” of high-rise building mockups staged on a vacant lot outside of Paris allowed Tati to position this all-too-familiar modern city into perfect blocking to push a relentless visual language that any urban dweller can relate to.

From the very first frame, this theme is communicated to us: a soft, puffy cloud emerging from behind the hard angle of a glass-and-steel building.

Tati plays with our expectations as reflections become ghosts and the “solidly built” modern world literally crumbles before the audience.

As with his spiritual predecessors Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, the actor/director combines comedic body language and larger-than-life scenarios to bring his message home, while delivering the elevated sense of humor which the comedic mirror produces.

Every scene in the film is filled with activity. Several funny things often happen at the same time in the same static frame. These are lost on the small screen.

Also cut down to size are the grandiose scenarios, which serve to befuddle the feckless Hulot as he tries to get everyday errands done.

While Criterion made a beautiful Blu-Ray of the film, it just does not work on a television set. Restored 65mm prints have been lovingly curated by Tati’s daughter and are absolutely not to be missed should luck bring one into an audience’s proximity.

Author Bio: Argentinean-born New Yorker Miguel Cima is an NYU Film School alumni and a veteran of the entertainment biz (Warner Bros, Dreamworks, MTV, etc.). An accomplished writer, filmmaker, and comic book creator, Miguel’s movie, Dig Comics, won Best Documentary at the San Diego Comic Con. A culture junkie, foodie and world traveler, he is happily unmarried to a rockin’ heavy metal vocalist gal and slavishly serves his true masters – two dogs and a cat.