7. Beauty and the Beast (Juraj Herz, 1978) / Czechoslovakia

Juraj Herz of The Cremator fame realizes horror potential in the famous fairy tale and turns it into a dark and visceral gothic fantasy-melodrama. From the very prologue and the naturalistic scene of preparations for the feast (which will have vegetarians screaming in terror), you can tell that you’re in for something quite different.

Initially, we see several carriages passing through the black forest shrouded in mist (and gossips), while being over-flown by crows. Later, it is revealed that they carry luxury goods, as a dowry of a wealthy merchant’s elder daughters. But, the procession never reaches its destination which leads to the merchant’s financial downfall, his visit to an ostensibly abandoned castle and the picking of a cursed rose.

The rest of the tale is well-known and yet this incarnation seems refreshing in its bleakness, as if it were an adaptation of the Grimms’ writings. Its original title Panna a netvor is literally translated as The Virgin and the Monster, indicating the theme of innocence vs cruelty and a romance with a little bit perverse undertones.

Zdena Studenková has all that it takes for the role of the virtuous beauty, Julie, whereby her nasty Romeo (played by actor, dancer and choreographer Vlastimil Herapes) appears to be a unique hybrid of a man and a raptor. Their love is born in dilapidated and nightmarish surroundings of living gargoyles, coffin-like beds, moss-covered statues and sulphurous ponds, with white Julie’s dresses as a counterbalance and the sounds of organ pipes floating through.

8. Konopielka (Witold Leszczynski, 1982) / Poland

This metaphorical, ironically inclined film which takes us to a remote dorp of Taplary is based on the novel of the same name by Edward Redliński who has frequently explored the conflict between provincial mentality and progressive ideas.

The superstition, the fear of the God and the narrow-mindedness are channeled through all of the Taplary inhabitants, but primarily through Kaziuk, a boorish, illiterate and grouchy pater familias. His family – an elderly father, a bachelor brother, an obedient wife and three children – lives by his own rules. But, everything changes after the arrival of a pretty school-mistress who brings the “coldness” to the “warmth” of his home and transforms his dreams from religious to erotic.

In addition to being skillfully directed and excellently written, Konopielka has an attractive high-contrast B&W cinematography and nearly every frame is nothing short of a masterpiece. A cozily bleak atmosphere, infused by both subtle and vulgar humor, owns a lot to the mélange of ambient noises and a couple of, in a way, opposed musical themes.

The authentic and immersive environment (kudos to set and costume designers) is complemented by the unaffected acting of the whole ensemble.

9. The Angel (Patrick Bokanowski, 1982) / France

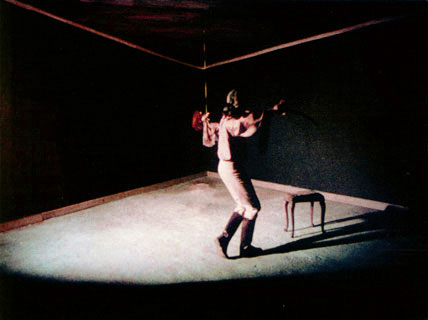

Imagine climbing an Escher-like staircase of a bizarre building in the middle of surreal nowhere. On the first floor, you come across a fencer who thrusts, over and over again, at the doll hanging from the ceiling of an empty room. Further up, you see a maid who brings a jug of milk to a handless man, while a youngster plays with the shiny pearls in the hallway.

Then, you peek into a middle-aged gentlemen’s bathroom, prior to visiting a library, whose fez-wearing employees are all identical. You don’t realize they’ve been preparing to release a naked woman from her two-dimensional prison. She’s a model for a medieval artist trapped in the world of his own engravings. When you finally reach the top, an enigmatic entity leads you – bathed in bright light – to a higher realm.

Patrick Bokanowski’s sole feature film is what you might call a “high brow” phantasmagoria –abstract, interpretative, expressionistic and slightly creepy. Its sophisticated, referential visuals and an experimental score composed by the author’s wife Michèle make it seems like an embodiment of a supernatural being’s chaotic thoughts.

The questions pose themselves: Is there a meaning hiding in the twisted reality of this trip? What is the true nature of cinema? Are we all freaks in the eyes of an Angel?

10. The Touch (Amanzhol Aituarov, 1989) / Kazakhstan (Soviet Union)

Aituarov’s stupendous debut The Touch (Prikosnoveniye) brings a fairy tale-like story of the star-crossed lovers’ past life. First, we “meet” the couple through their poetic dialogue which is heard during the prologue, as the camera “caresses” the objects in the dimly lit room of the present.

Shortly afterwards, we are taken back to the times of yore – a blind shaman-girl is saved from being raped by a runaway slave who joins her quest for “the land behind the blue mountains”. She refuses to admit she’s in need of a protector and he – living like a lone wolf for far too long – has never felt the warmth of another human. Together, they face a lot of obstacles in the wilderness and the town in ruins, eventually falling for each other.

An odd amalgam of poignant drama, uncommon road-movie and low-key fantasy provides an interesting viewing experience – it’s almost like Jodorowsky and Parajanov joined forces and went to direct a forgotten Kazakh legend. There’s an aura of mysticism surrounding the narrative and it probably stems from the cultural specificities.

The dreamlike proceedings are beautifully captured in the grainy photography dominated by earthly colors, whereby the ambient-folk-electronic score lends them a surreal vibe.

11. The Juniper Tree (Nietzchka Keene, 1990) / Iceland

One of the grimmest amongst the Brothers Grimm lesser known fairy tales is reimagined as an esoteric and meditative arthouse drama/fantasy in the vein of Bresson and Bergman. Finished in 1986, but not released until 1990, it is Nietzchka Keene’s and Björk’s feature film debut.

The original story deals with a wicked stepmother who decapitates her stepson and blames her daughter for the act, then turns the boy into a pudding and serves him to his father. Keene’s version (which cites several verses from T.S. Eliot’s “conversion poem” Ash Wednesday as well) makes quite a bit of changes, including witchcraft and the returning spirit of the dead.

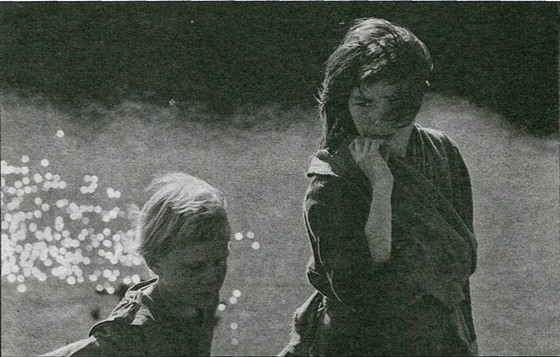

Preadolescent Margit (19-yo Björk, brilliantly unaffected) and her older sister Katla (Bryndis Petra Bragadóttir) flee their village after their mother (Guðrún Gísladóttir) is turned to ashes on the stake. Katla puts a spell on a young widower farmer, Jóhann (Valdimar Örn Flygenring), but his son Jónas (Geirlaug Sunna Þormar) stands in the way of her happiness…

With merely five characters (four of whom are alive), there is a “chamber ensemble” feel to The Juniper Tree. Deliberately paced, wonderfully photographed and sonically brooding, this moody, hypnotic little piece of seventh art is recognizably Scandinavian.

12. Twilight (György Fehér, 1990) / Hungary

The first of only two big-screen features of György Fehér is a depressive, aesthetically refined crime-mystery Twilight (Szürkület) – an adaptation of the screenplay for It Happened in Broad Daylight which was rewritten as a novel titled The Pledge: Requiem for the Detective Novel.

According to the initiated, this story is pretty faithful to the original one by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, even though it’s secondary to a dense, haunting, funeral-like atmosphere. A police investigation of an eight-year-old girl’s murder serves as a central motif of the meditative long takes interconnected by a melancholic musical theme which resembles a lullaby for the dead.

Powerful in its dreariness, Twilight seems like a cinematic equivalent of darkwave drones or a gray, foggy and rainy autumnal day – it is a harrowing combination of minimalist narrative, prolonged periods of silence and gritty B&W photography. (DP Miklós Gurbán will collaborate with Tarr on Werckmeister Harmonies ten years later.)

As the camera slowly glides over characters’ tired faces, barren trees, muddy pathways, decrepit facades and stuffy rooms, a viewer finds him/herself in a position of a dreamer who’s stuck in a claustrophobic nightmare.

13. Fire-Eater (Pirjo Honkasalo, 1998) / Finland | Sweden

A story of a fire-eater’s ups and downs (mostly downs) is something you definitely don’t see every day, but it surely makes for a powerful and visually poignant drama. Directed by a woman, written by her partner, who also happens to be a woman, and starring mostly women of different ages, Fire-Eater (Tulennielijä) could be easily labeled as female-centric… and yet, the ladies here are far from being romanticized.

At their infancy, twin sisters Irene and Helena are abandoned by their libertine mother and left with an incorrigible communist grandmother, who calls them Vladimir and Ilyich after her idol. Their earliest childhood is “undermined” by Stalin worship, which is actually sweet compared to what follows. And the orphanage is not the worst part of their experience…

Told from the perspective of Helena whose middle-aged life is one of decay and endless wandering, the narrative is focused on the past events of competently captured sorrow, misery and (clinical) depression, as well as of strong sisterly love and small moments of joy.

Both the present of grainy B&W imagery and the past permeated with vibrant colors are equally soul-crushing, yet beautifully portrayed. Helena doesn’t speak much, probably because she believes that “mouth is a selfish and dirty hole” and that’s where the looks, gestures and compelling choir-heavy score come to replace the words.