A second batch of lesser-known films from all around the world adds a little bit more variety. One of the entries is so obscure it doesn’t even have an official international/English title, while some others are unfairly marginalized. From Hungarian film-opera to Thai romantic western-melodrama, you’ll certainly find something to your liking.

1. Diamonds of the Night (Jan Němec, 1964) / Czechoslovakia

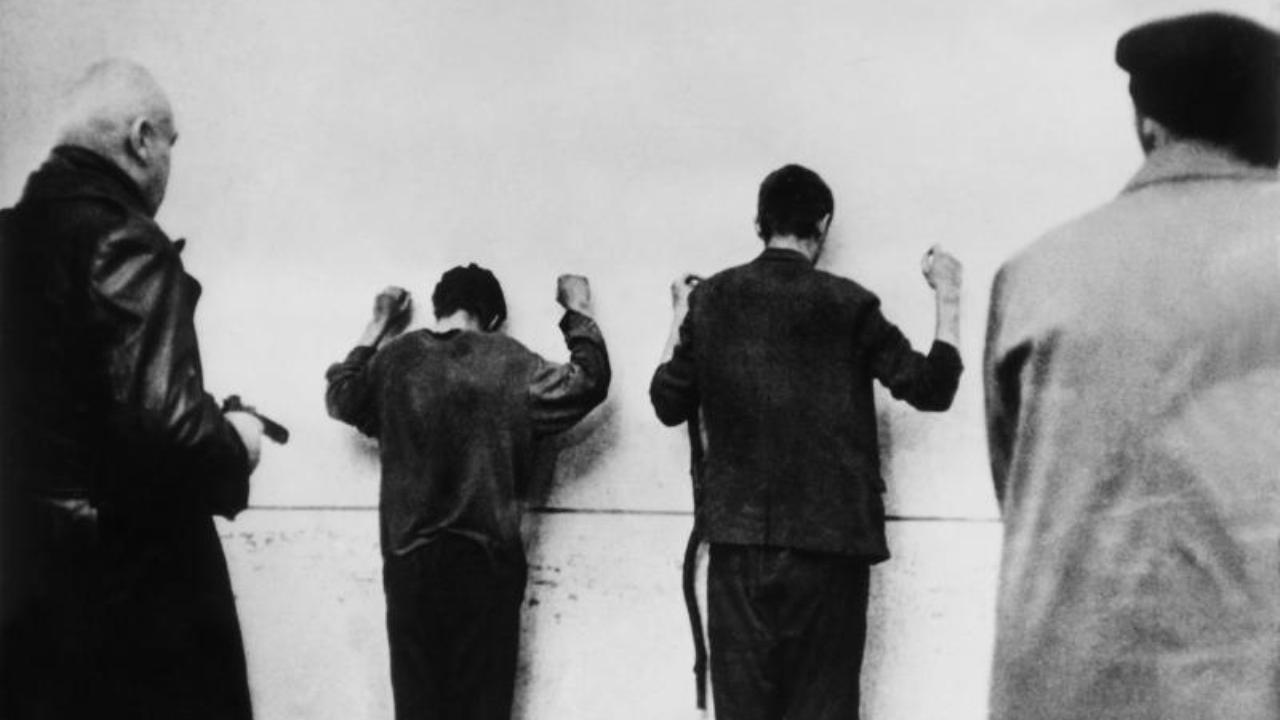

A feature debut for one of the most prominent figures of the Czechoslovak New Wave, Diamonds of the Night (Démanty noci) is the adaptation of Arnošt Lustig’s autobiographical novel Darkness Casts No Shadow (Tma nemá stín). This experimental drama revolves around two Jewish youngsters who manage to escape the train heading for a concentration camp, only to be left at the mercy of the hostile Sudety mountains.

By breaking the rules of conventional storytelling, reducing the dialogues to a bare minimum and relying upon his protagonists’ turbulent thoughts, Němec masterfully portrays fear and despair, the physical exhaustion and the state of the boys’ tortured psyche. The closeness of DP Jaroslav Kučera’s hand-held camera leads to the subjectivization of their nightmarish experience.

Unfulfilled dreams, disorienting hallucinations and fragmented memories of hard, yet free life in the city (of Prague?) are more lucid and oppressive than the relentless reality with the odor of bare survival. It is hard to distinguish where or when the obtrusive fantasy ends, but it is the very enigma that renders the film impressive.

Frequently odd juxtapositions, accompanied by the overemphasized sounds, make the unnerving atmosphere even more bleak and brutal. Němec’s brilliant direction and Miroslav Hájek’s unusual editing are complemented by the top-notch B&W cinematography and excellent performances of Ladislav Jánsky and Antonín Kumbera.

2. Nocturne 29 (Pere Portabella, 1968) / Spain

Another prominent figure, but this time of Spanish cultural scene and political history is Catalonian filmmaker Pere Portabella whose oeuvre is deeply influenced by the cooperation with Luis Buñuel. His directorial debut Don’t Count with Your Fingers (No compteu amb els dits) serves as the basis for an anti-bourgeois “drama” Nocturne 29 (Nocturno 29) whose title refers to the dark years of Franco’s regime.

The film’s narrative structure which mimics, deforms and destroys the TV-ad format is built upon the succession of “semi-autonomous scenes” occasionally interconnected by the attractive, nameless heroine (played by Lucia Bosé). A non-sequitur conversation with her middle-aged husband and “super-realistic fragments that expose the irrelevance of daily life” (in the words of the director himself) suggest the story of adultery which remains sketchy.

The unhealthy state of society under dictatorship is colored absurd and puzzling by Portabella who skillfully avoids censorship and keeps his audience at a safe distance. However, even the most preposterous sequences are imbued with meaning in the context of suppressed liberties.

Beautiful in their grainy, high-contrast B&W gloominess (and weirdness), all of the vignettes are marked by a subtle provocation, but they also require a great deal of patience.

3. The Plea (Tengiz Abuladze, 1968) / Georgia (Soviet Union)

Epic verses of Georgian poet and writer Vazha Pshavela (1861-1915) are transformed into a freely structured visual poem, powerful and mystifying in its grim grandeur. Composed of mesmerizing, awe-inspiring images of sharp faces, craggy mountains, stone structures and national costumes, it recalls the works of Bergman, Tarkovsky and Parajanov.

The themes of pride, honor, beliefs, revenge, mourning, living and dying, The God and the Devil (who appears as a goatherd) are interwoven into the impenetrable whole deeply rooted in Georgian tradition. The Plea (Vedreba) makes you feel lost in the forest of arcane symbols and cultural references, yet it invites you to think or, rather, dive into the pristine subconscious.

Distorted through the prism of incorrigible human nature – both beautiful and revolting – the film’s reality of non-glorified past seems like a sullen dream of opaque grays. Through many scenes of death related rituals, Abuladze establishes a kind of a funeral, slightly surreal atmosphere which keeps a firm grip on the viewer.

With its atypical rhyming narrative, swooping score and memorable visuals, The Plea is a rare black pearl of Eurasian cinema.

4. Malpertuis (Harry Kümel, 1971) / Belgium | France | West Germany

“It’s pretty, but it’s a bit difficult to understand… Somehow it makes me think of all kinds of things, but I’m not sure exactly what.”

These words we hear at the very beginning of Malpertuis (aka The Legend of Doom House) perfectly epitomize its whimsical nature. Based on the novel of the same name by “Belgian Poe” Jean Ray, this genre defying film is a gothic-mythological fantasy, a period psycho-romantic-melodrama and a horror mystery all at the same time. It is a nightmarish odyssey with a twist ending which corresponds with the quote by Lewis Carroll: “Life, what is it but a dream?”

Idiosyncratic, “carnivalesque”, erotic and creepy, Malpertuis is characterized by a fascinating, often very colorful set, costume and lighting design, whose dark, mystical, almost unearthly beauty is captured by the equally exquisite photography.

An interesting, international ensemble of actors brings to life a motley crew of bizarre characters who slyly hide their true faces, while you’re never sure where they will take you. A protagonist Jan who looks like a bleached blonde hero from an ancient Greek legend is played by Mathieu Carrière who is partnered with Susan Hampshire in a quintuple role and Orson Welles as a devilish “pater familias”, Cassavius.

In respect of their story, the less you know about it, the better – simply put, everyone has to experience it for themselves. And by virtue of Kümel’s precise helming, that experience is great.

5. Devičanska svirka (Đorđe Kadijević, 1973) / Yugoslavia

“The end is the beginning and the beginning is the end.”

Shown a few times on a Serbian state television, Devičanska svirka (A Maiden’s Music) is probably not available via legal means which is a shame, given that it’s one of the most precious and unique films from the region. This wonderful dark romance with the elements of horror and mystery is a small screen adaptation of Ivan Raos’s short story meticulously directed by Đorđe Kadijević – a respectable filmmaker, art critic and historian.

It follows a young man, Ivan, who interrupts his journey in order to take a rest near a lowland castle considered haunted by the locals. After the unfortunate event in which a boy gets accidentally killed he ends up in that feared place, owned by an attractive, enigmatic widow, Sibila. Upon his arrival, Ivan starts to hear a strange music and slowly realizes that he can not leave…

Grimly atmospheric and sonically ethereal, as well as quite chilling, A Maiden’s Music brims with gorgeous monochromatic imagery draped in thick shadows. It seems like a cinematic precursor-equivalent of some gothic metal song performed by, let’s say, Theatre of Tragedy.

In the portrayal of their characters, Olivera Katarina as divinely dominant Sibila and her partner Goran Sultanović as perplexed, enchanted Ivan are both admirable.

6. Bluebeard’s Castle (Miklós Szinetár, 1981) / UK | Hungary

Another TV adaptation is based on Béla Bartók’s sole opera whose libretto is inspired by a French fairy tale La Barbe bleue, Hungarian folk ballads and the poetry of symbolism. Bluebeard’s Castle (A kékszakállú herceg vára) can be seen as an intriguing parable on trust and communication or an allegorical fantasy with psychological subtext.

Soprano Sylvia Sass plays a naïve, stubborn and, above all, dangerously curious Judit whom Bluebeard (Kolos Kováts, bass) brings before his castle shrouded in darkness. He asks her if she really wants to stay and offers her the last chance to return to her father on the estate bathed in light. In spite of the rumors, she renounces her ways and enters the home of many secrets, seven of them hiding behind the locked doors.

The claustrophobic, windowless interiors of “tearful” walls and oppressive shadows reflect the enigma that surrounds the introvert, melancholic, seemingly hardhearted, yet tragic (anti)hero. His fear of loneliness is what makes him the way he is and in the end, it proves to be justified and gives a new meaning to the story whose psychosexual aspect is kept intact.

Iván Márk’s cinematography hits the mark in spite of the sets’ obvious artificiality, while London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Georg Solti, evokes the intensity of Bartók’s score. Also praiseworthy are “bel canto” performances of Sass and Kováts.