7. O Brother, Where Art Thou (2000)

The way Roger Deakins can transform the visual narrative style is outstanding here once again. This modern satire evaluates the precarious Ulysses, Pete and Delmar with a sense of sensible appreciation for the values of folktale and what a voyage means in the full spiritual and down-to-earth sense.

This triumvirate of personas represent a fractured intention of dismemberment of traditional chores. The idea of escape and alienation are visually captured in long shots, over-the-shoulder followings, and nontraditional uses of high and low angle takes, to extract a well-founded study of men and the condition of escape with a great deal of replicated humor and sarcasm.

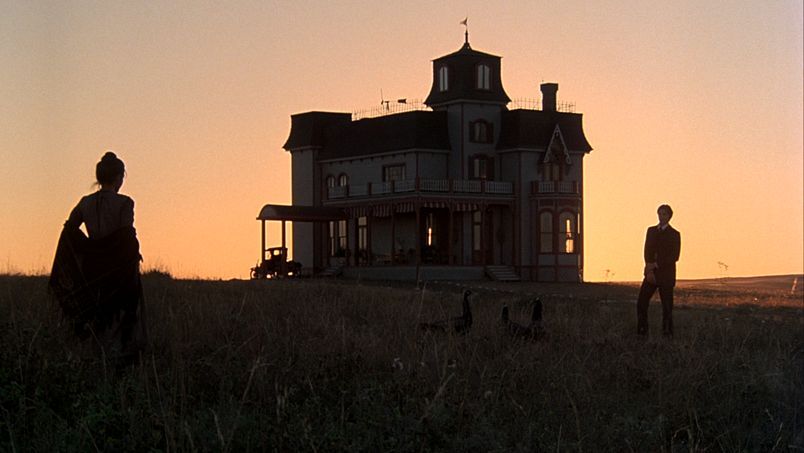

6. Days of Heaven (1978)

Terrence Malick again makes enigmatic use of visual narrative to convey a story that, in theory, doesn’t seem to be willing to tell much. This story of Bill and Abby in Texas could have gone in a totally different direction if not for the poetry that is found in these frames. Néstor Almendros and Haskell Wexler utilize ambience and form to dictate the rhythm of content.

Edward Hopper’s painting, The House, inspired how structures can also tell a story and be a protagonist of it. Beautiful two-shots and accommodation of light in sub-exposed subjects were used to tell a story of love and trickery that proves to be represented in the counterweighted balance of the symmetry in every picture, opting to tell an explorative spectacle to viewers about the subject of love, tradition, menace and structure.

5. Barry Lyndon (1975)

John Alcott and his vision are the only instruments that Kubrick needed to create a story so rich like this one, in spite of stylized long shots. This is a film that transforms the sense of location and setting like no other, being able to allocate establishing shots with an unnerving depth for sensation that no other director seems to utilize to a full extent, opting to have the establishing shot as a resource for transitions only.

The images are composed in a beautiful symmetrical tone, varying with a rule-of-thirds composition to picture the subject isolated by consuming surroundings. Conversations and encounters have an angle to the take, whereas the beautiful stills and balance of the picture are interwoven to a detailed sense of atmosphere and ambience that are ever-present and encapsulating to the experience.

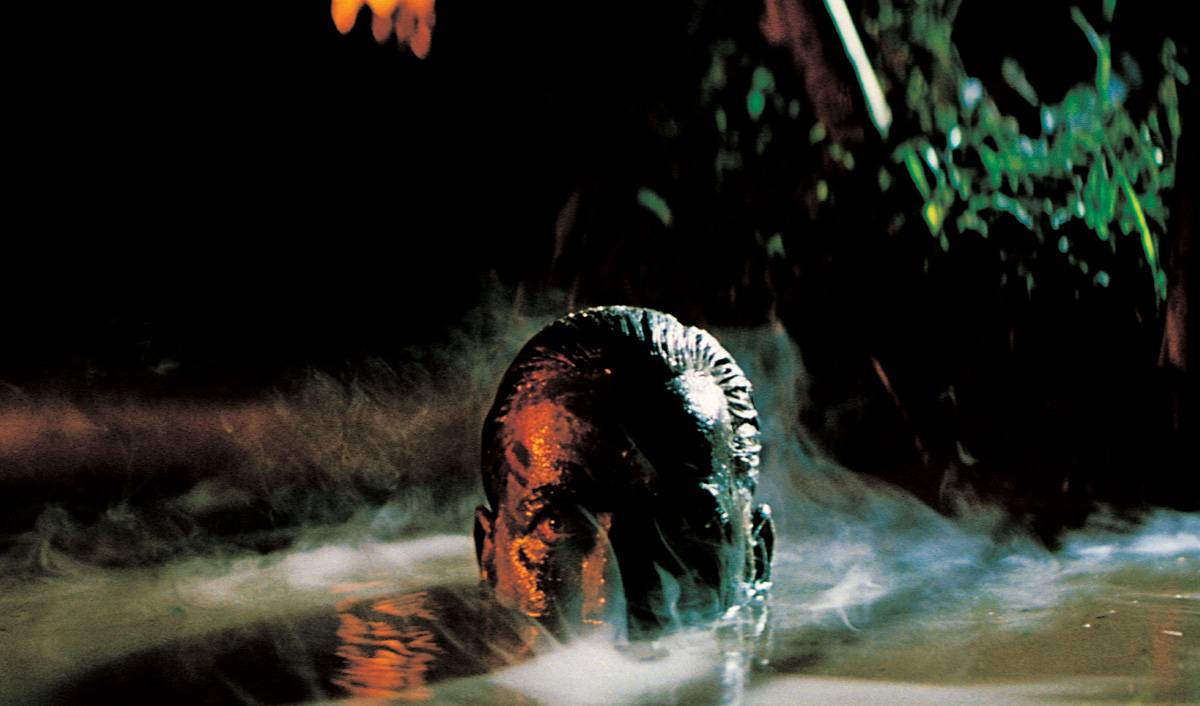

4. Apocalypse Now (1979)

Walter Murch is as much of an author here as is Francis Ford Coppola and Vittorio Storaro. The picture is met with editing, direction and a visual style that sum up the distress that is felt through the transformative experience of war.

There is a compromised sense of composition here that allows Martin Sheen to withstand the gaze of the camera and allow the spectator to see in every establishing shot that is reformulated to set the mood, rather than only the place of things. Also, the soft high-angle shots that are deployed work to allow Sheen and other characters to be swallowed up by specific dire conditions, which ultimately prove to be the large arc of trouble and containment that war manages to be.

3. Citizen Kane (1941)

Orson Welles constructs with Greg Toland THE story of the ages. How low and high angle takes dominate the criteria of technique here, should be the motto of communication of film: if you choose a technique and repeat it throughout, it is a style, and if it is yours, make it like no one else.

The course of dialogues and actions are the clear protagonist here, but the visual aid is never left behind, being employed to empower the flow of events and how Charles Foster Kane is so maligned by the conditions he confronts throughout his storyline with incredible use of extreme close-ups for key details (“Rosebud”) and tempo-dictating medium-shots for important bytes of information, in what is a reverberating experience of investment and depth of a story.

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

This is a film that no matter which criteria is analyzed, should be present. Either by narrative, dialogues, atmosphere, lightning or other structure or technical criteria, this movie crosses all boundaries to be a masterpiece of composing something that reverberates in every level of our biology.

This film can’t work on the obvious, being deployed in an subjective manner with important transitions of picture and mesmerizing composition. The viewer must not be distracted by the sole intention of communication, leaving Michael Bay-esque flares and patching of flashbacks and other narrative savings to be protagonists elsewhere.

Kubrick opts for a minimalistic approach to things that aids his communication, employing the beautiful canvas of the enigmatic, adjusting center-weighted imagery with a balance that transcends the frame and moves into transition of the moving picture, balancing evolution and the primitive aspects of film with the awe of discovery and involvement with creation.

1. The Tree of Life (2011)

Without a doubt, Emmanuel Lubezki’s finest work tops this list. This film works by showcasing the intimate journey of a family through time, with interlaced stills of the genesis of the universe, conversing with the drastic turns that are rehearsed in the story of a family.

Grandiose and symmetrical long shots are used in the mold of Kubrick – perhaps the master of establishing shots – to set the tone and vibrancy of what creation is, be it men or Godlike. The camera swiftly flows and travels with a humane arrangement, fixating on the visual silences of the film, giving so much rest and information that the viewer is challenged to continuously exercise and extract important rhetoric figures of what is constantly being communicated.

Author Bio: Guido Samame is an avid film critic, writer, indie music fan, producer and assistant to the professor at the Universidad de Lima in screenwriting. Currently residing in Lima, Peru; Guido can be found walking or driving around the sun thinking about some story to some nice tunes you have probably never heard of. You can follow Guido on Facebook, Snapchat or Instagram as @Guido Samame or @guidosamame.