6. Night of the Shooting Stars (1982)

The history of the cinema has been oddly dotted with the surprisingly fruitful partnerships by pairs of brothers ranging from France’s Lumiere brothers at the dawn of film history to the modern wonder of the Coen brothers in Hollywood. Italy’s contribution to this phenomenon was the team of Paolo and Vittorio Traviani, who have had long and distinguished careers.

For most of their span they were best known on the European continent but they enjoyed a moment in the international sun during the late 70s going into the 80s. Though their breakthrough was 1977’s Padre Padrone, for many critics and viewers their finest hour was Night of the Shooting Stars.

The story, set during the closing days of World War II as experienced in the Italian countryside, is couched as a remembrance told to a child in the then present day. During the war’s waning days, the retreating Germans are determined to leave nothing in their wake for the advancing US troupes to be able to use. They inform the inhabitants of a little town that they will burn everything except the church and the villagers are to go there for safety.

A large number of them do just that but an equally large number decides to go out and welcome the incoming soldiers, whom they are sure will be the better bet. This story could easily have been done in a realistic manner and in part it is done in that style but it’s also full of fantasy touches and comic moments and indelible imagery. Remarkably, it all comes together seamlessly.

The film won the top prize at Cannes and the famed US critic Pauline Kael, no pushover, to say the least, gave the film one of her most unrestrained raves. Sadly, though the film was Italy’s submission for the Best Foreign Film Oscar, the Academy, in its wisdom, said no. Even sadder, despite a few more notable films, the Tavianis faded from international view. However, they had one great moment, if nothing else.

7. A Nos Amours (1983)

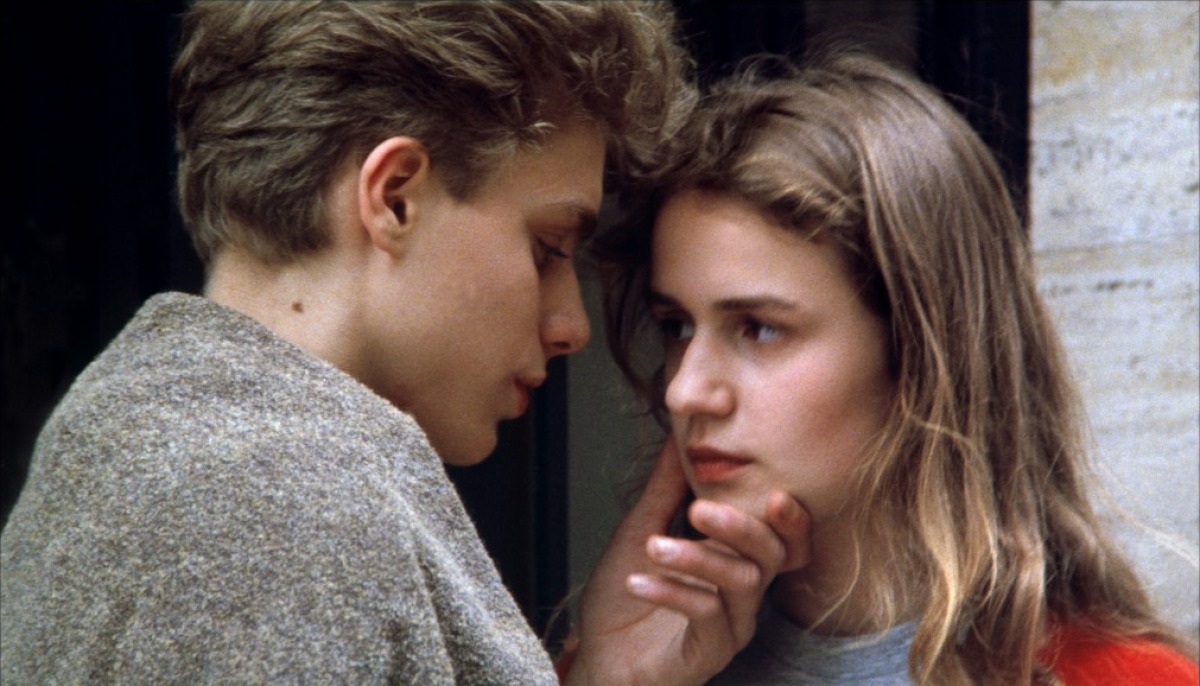

Another film maker who reached a fever pitch in the 1980s was France’s Maurice Pialat, who created four films, all critically acclaimed, during that decade. Though 1980’s Loulou has its partisans, the high point for many others was A Nos Amours (translated as To Our Loves).

Many have compared Pialat’s work to that of American independent giant John Cassevettes in that he always reached for a realistically pulsating narrative reflecting a recognizably lifelike quality in his work. This was well served in this tale of a 15 year girl, trapped in a miserable situation at home in a household of dysfunctional souls, who finds her release in unbridled sexuality. This leads to eventually to self-destructive abuse and a sad outcome.

The film is quite incisive and has a fine cast but the highlight is the discovery of the young actress playing the lead role. Sandrine Bonnaire would go on to become one of France’s top actresses, working with many renowned directors. This was her second film and it set the stage for the rest of the decade to be filled with excellent films and performances, making it perhaps her finest.

8. Vagabond (1985)

he next big step in Sandrine Bonnaire’s path to greatness was this film, in which her character is even more disconcerting than her troubled adolescent in A Nous Amours.

As Vagabond opens, that character is shown lying dead in a ditch where she has succumbed to exposure from the elements. The young woman is named Mona and the film flashes back to the start of the winter season as the obviously troubled character aimlessly wanders from one situation to another, belligerently refusing help from all who would or could aid her.

She tells one of the strangers she’s more sympathetic towards that she once had a good job in Paris but deserted it and any other responsibility and set out to find freedom. Only a brave actress would have had the courage not to play for sympathy. The value in the film is delineating a thorny character without softening and falsifying her.

The architect of this fine setting for the actress is one of the world’s most notable female directors, Agnes Varda. Starting out in the French New Wave period, Varda, while not unusually prolific, created a number of important films which honestly examined flawed and complex central female characters and she was able to adapt the freely passionate, experimental style of that period to the less showy vibe of a different film generation. (Oddly enough, she was married to the decidedly non-realistic film maker Jacques Demy, which was a true meeting of equals, though.) Vagabond stands as one of her great works.

9. A Room with a View (1985)

The long running team of director James Ivory and producer Ismail Merchant (long time life partners as well) provokes a rather complex reaction in many film fans. Their early films in the 1960s weremade in Merchants native India and many thought both men were Indian, though Ivory was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York.

Those films engendered a good art house reputation for the pair but in the 1970s they migrated to Ivory’s native land and started trying to find a broader audience with contemporary dramas, which met with little enthusiasm for the most part, and literary adaptations, often the subtle works of the great US author Henry James.

Many compared these films to the PBS staple Masterpiece Theater, and that was not a complement. In the 80s the team looked for different authors and hit pay dirt with their adaptations of the works of British author E.M Forster. Their first, and perhaps their most beloved film ever, was their adaptation of his classic novel A Room With A View. T

he film, set in the Victorian age, details how two slightly star-crossed young people (Helena Bonham-Carter and Julian Sands, both newcomers at the time) find the courage to push aside stuffy and restricting social conventions in order to find a vital love and lifestyle in opposition to the stuffy fabric of the social life of their day and place.

In contrast to the rather stilted previous adaptations the pair had previously produced, this film had an appealing story, fine production values for a modestly budgeted picture (with location work in both Italy and the English countryside), and a sterling cast with also included Maggie Smith, Denholm Elliott, Rupert Graves, Judi Dench, Simon Callow, and one of the first memorable performances by the great Daniel Day-Lewis.

The result was a hit with both critics and the public. Though Merchant-Ivory would still have their uneven moments thereafter, this film became a model for some of their career best work.

10. Jean de Florette/Manon of the Spring (1986)

One of France’s great artistic treasures of the 20th Century was writer and film maker Marcel Pagnol, who could, with equal deftness, tell both dramatic and comedic tales set in his native rural Provence, one of France’s loveliest sections. In Pagnol’s own time, his efforts were considered pleasantly provincial in an age aiming for sophistication.

In the latter part of the century, Provence started to find a greater interest from the public than it had known before and Pagnol’s work was taken up by a new generation. The expert film maker Claude Berri created what might well be the finest tribute to Pagnol with his adaptation of the two part novel The Water of the Hills.

The story, redolent of Balzac and Dickens, is set in the Provence of the early 20th Century and tells of how a cruel and wealthy farmer (Yves Montand) and his unscrupulous nephew (Daniel Auteill), realizing they could reap a fortune growing carnations if they had enough land, scheme to steal the farm next door, which has been inherited by a pitiful hunchback (Gerard Depardieu), who is the son of a woman the old farmer had loved and lost.

The two men have stumbled upon the hidden source of the land’s water and seal it up, setting the newcomer up for tragedy. The second part, taking place many years later, focuses on the hunchback’s lovely and vengeful daughter (Emmanuelle Beart), who likewise stumbled on the neighbor’s cruel plot as a young girl and has bided her time until fate allows her take her revenge.

Fate also gives the old farmer a jolting and ironic shock at the end (though logical enough not to be a complete surprise to the viewer). This two part epic is long, richly detailed, and deeply satisfying. It’s not cutting edge but, like Pagnol’s own work, it tells a compelling story which easily holds the viewer’s interest.

The cast was well chosen, featuring some of France’s greatest actors, giving career best performances (and it particularly stands as a monument to Montand’s famed career).

11. Babette’s Feast (1987)

In 1987 art house fans and critics were stunned by Babett’s Feast for two reasons. First, the film came out of virtually nowhere since its director, Gabriel Axel, had a long career in Denmark while never achieving international recognition.

Secondly, the quality of the film was so very good that it ended up winning many awards, including the Oscar, and became the year’s most cherished art house hit and is now a beloved classic. (Sadly, it didn’t majorly change Axel’s fortunes but did give him a great moment in the major leagues.)

The film is now also regarded as one of the finest examples of literary adaptation on film. Taken from a short story originally written for a popular magazine by Isaac Dinesen (actually Baroness Karen Blixen, whose own story was told in Out of Africa), the film does a fine job of capturing the author’s noted spiritual and emotional qualities and finds a cinematic equivalent to her subtle and incisive style.

In a small village in 19th century Denmark, two elderly sisters (Bodil Kjer and Birgitte Federspie), who have become the custodians of their late father’s extremely austere religious sect, take in Babette (a superb Stephane Audran), a political refugee from France who arrives with virtually nothing.

The sister’s have very little and can offer her only food and shelter in return for her work as cook for them and those they charitably feed with the plainest of foods. Babette, a trained chef, stoically prepares the lusterless meals but then fate smiles on her when an old lottery ticket rewards her with money.

Instead of returning to her former life, Babette uses her winnings to prepare a lavish meal, the likes of which no one in the town has ever before seen, let alone experienced. Fearing the temptations of the flesh and of gluttony, the sisters and their followers determine that they will not show any joy or delight in the meal. However, the sincere and generous gift Babette renders will have a surprising spiritual effect on the recipients.

Most serious and finely crafted modern cinema sidesteps anything like a happy ending for fear of seeming false. Babette’s Feast is one of the very few great films which ends on a note of plausible uplift, though the happiness is shown to be of the moment and did come at great sacrifice. It was and remains a most moving experience.

12. Cinema Paradiso (1988)

The Italian cinema somehow seems to have an honest proclivity for deeply felt and warmly rendered nostalgia which doesn’t come across as false or calculated, as it often does in the cinema of other countries. Following it the steps of Frederico Fellini, writer-director Giuseppe Tornatore tells a tale of the events which shaped his professional and personal life.

Cinema Paradiso, the first and biggest hit in the director’s mildly successful international career, follows a noted young Italian director as he journeys from his present-day home in Rome back to the little town of his origin for the first time in many years. He’s returned for the funeral of a most important and influential person from his past.

The surprise concerning this event is that the beloved person is not a relative, teacher, or spiritual leader in the accepted sense but, rather, the long time projectionist at the local movie theater. As a fatherless little boy, the main character, Salvatore (played by Salvatore Cascio, Marco Leonardi and Jacques Perrin at various ages), takes to hanging around the one movie theater in his small town, a place made even more magical by the war era events which are overshadowing life there.

The projectionist, Alfredo (the fine French actor Phillipe Noiret, in a career best turn), is the keeper of the dreams in this place and the boy and he take to each other to the extent that they end up thinking of themselves as father and son. This relationship will endures through many of the boy’s normal coming of age trials and tribulations and culminate in a gift in a film can the older man leaves to him.

Sentimental? Sure it is, but life is full of sentiment and honest sentiment is always welcome, as proven by the film’s warm reception. This film was originally nearly three hours long but when Miramax president Harvey Winestein released it in the US it was edited down to a bit over two, echoing the film’s censor-priest, who would remove all the scenes which offended him.

After the film’s success the original was released on video but nearly all who saw it agreed that Weinstein had, in fact, seen the fine average length film inside the rather lumbering big one.

13. Pelle the Conqueror (1986)

It’s quite ironic that the great Swedish actor Max von Sydow will be eternally remembered in film history as one of the key players in the cinema of Ingmar Bergman and gave many notable performances in Bergman films but, largely due to the Academy’s relative indifference to international cinema, he was never honored for any Bergman film.

In fact, his two nominations to date came late in his career and the first was for an intimate and touching little film which, ironically, announced the arrival of a new talent on the international scene, director Billie August (to the surprise of no one, August’s next project after this film was directing The Best Intentions, a script written by Bergman, then retired from directing). This was another of the father-son stories which European cinema seems to do so well and which are scarce in US film making.

The story, taken from a novel considered a classic in Sweden, is set in the 19th century. A less than gracious boat brings a load of Swedish immigrants to Denmark, among them widowed Lasse (von Sydow) and his young son Pelle (Pelle Hvenegaard).

The father and son have no education to speak of nor any special training but they are determined to make a better life for themselves than the one which they knew in Sweden. (Between this film and director Jan Troell’s 1972 and 73 epic The Immigrants and The New Land, also with von Sydow in the cast, 19th century Sweden is pictured in a very poor light.) The two find work as farm hands and are treated as no better than paid slaves.

The lengthy film becomes a testament to the endurance of the main characters and the sustaining love which they share. One odd point is that von Sydow virtually always played austere if not menacing characters in Bergman’s films but here is he quite kind and loving, yet still most convincing.

The film became one of the very few to win both at the Oscars and the grand prize at Cannes and it set August on what has become a mostvibrant career.