14. The Sorcerers (Michael Reeves)

Weirdly, there are two out-and-out horror films that also belong to this sub-genre, both from the same director. Witchfinder General (aka The Conqueror Worm) is well-known – Ian Ogilvy’s dashing soldier taking on the forces of corruption in the form of twisted magistrate, Matthew Hopkins.

But even more interesting is its predecessor, one of the last vehicles for Boris Karloff, who plays an elderly scientist and inventor of a machine that allows the user to control someone else’s actions and experience the resultant sensations.

He and his wife subject a young man-about-town (poor Ian Ogilvy again) to the device, and from then on have him riding fast motorcycles round country lanes and killing the odd girlfriend.

Again, it’s a clever take on the older population secretly profiting from the activities of a younger generation they purport to despise. It’s also an ingenious allegory of cinema itself, slyly alluding to the pleasure the audience enjoys in acts of violence or passion undertaken at a safe distance by other characters (think of The Sorcerers as a poor man’s Peeping Tom).

And as such, it will be recognised in years to come as the ’60s answer to Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, only a lot less pompous and a great deal less ugly.

15. Sleeping Sickness (Ulrich Kohler)

This German film played to acclaim at festivals, but has since vanished from view and is not available on disc with English subtitles. Which is a crying shame, because it is one of the finest portraits of African colonials made by a Westerner, a casually subversive but highly accessible art movie, which has a feel for magic realism that matches the best work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Like the latter’s Tropical Malady, the narrative takes the form of a diptych, the first half following the life and work of a European doctor in Cameroon, who has become involved with one of the local women.

In the second half, a black colleague from France is asked to investigate the doctor, Kohler thus offering a twist on Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, in which the doctor becomes a mysterious Kurtz-like figure and Africa becomes a scene of moral confusion to a black man rather than a white man.

It’s a film that’s not the slightest bit interested in political correctness, but is very much interested in truth, and hopefully will emerge not only as one of the best German films of its era (superior to Petzold, for example) but a crucial text in First World-Third World relations. Watch out for the hippo.

16. Chung Kuo China (Michelangelo Antonioni)

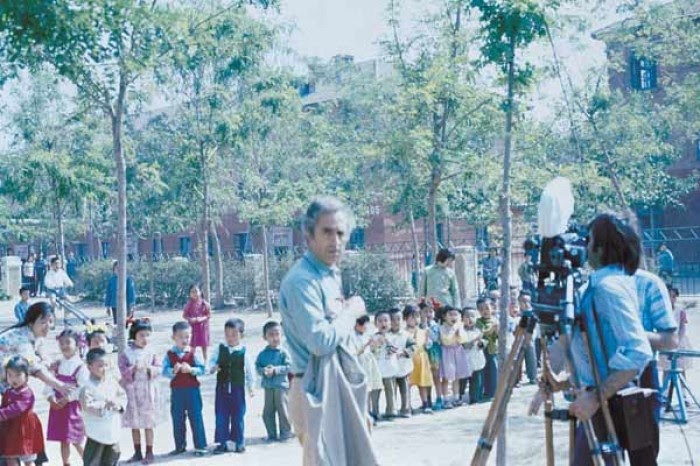

As China’s economic and political progress continues, future film scholars may look back for evidence of the seeds of that progress, and they would find an intriguing case study in this documentary series Antonioni made for Italian television in the early ’70s.

The director was invited over to film Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in action, but the resultant footage met with Mao’s disapproval and the film was dogged with criticism from the Chinese regime wherever it played. Which seems odd when you consider how low key and unconfrontational it is.

Indeed its strength as a documentary is that it resolutely adopts the attitude of a tourist, an alien, just trying to capture what they find interesting, instead of that of an omniscient narrator. Which is why, at one point, Antonioni jumps out of his escort’s van to film an impromptu street market taking place in a country lane, a little bit of domestic capitalism going on under the disapproving authorities’ noses, a seed…

Chung Kuo China should also act as a corrective to those that find Antonioni a cold director only interested in architecture and empty spaces; here, his focus is on people, faces, gatherings, not buildings, a clue that his work was always engaged with human emotion and inner feelings, and warmer and more sympathetic than his reputation often suggests.

17. Psy-Warriors (Alan Clarke)

Psy-Warriors is a filmed TV play, written by David Leland, which portrays in harrowing detail the systematic torture undergone by three captured soldiers in an underground bunker. As directed by Alan Clarke, it couldn’t be more stark, more brutal.

The rooms in which the action takes place are white and featureless, and at first little background is given on the identities of either interrogator or victim, the more to concentrate the viewer’s attention on the battle of words and bodies taking place.

It’s the kind of worthy videotaped drama that is often lightly patronised as “masterpiece theatre”, but to come across it in 2016 is a bracing experience. Because its discussion of Middle Eastern conflict, the politics of terrorism and counter terrorism, and the dehumanising effect of torture is more concentrated and apposite than in any comparable feature in today’s cinema.

Furthermore, Clarke’s foregrounding of script, something that might be criticised as the antithesis of good filmmaking, only serves to demonstrate how committed Clarke is to the issues at hand, stripping away, Bresson-like, any elements that distract from the core momentum.

It’s alleged that Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers was once shown at the Pentagon to instruct staff about guerilla tactics; it wouldn’t be at all surprising if Psy-Warriors takes its place as a comparable text on psychological warfare.

18. Queimada (Gillo Pontecorvo)

Talking of Pontecorvo, he actually made two masterpieces, but the second is far less well-known. That may be because, in English-speaking territories, it is still only available in truncated form, and the restored version unfortunately has lead actor Marlon Brando dubbed into Italian. But if some kind Blu-Ray label could work their magic and edit in Brando’s rather good British accent, this film might yet find the fame it deserves.

The antihero of the story is Walker, an agent working on behalf of the Empire, stoking up a revolution among black slaves in a Portuguese colony in the Caribbean.

Hailed by Edward Said as “the best film ever made about neo-colonialism”, it actually benefits from being presented as a ripping yarn, complete with bombastic score from Ennio Morricone, because it draws us, as a Western audience, into admiring Walker’s wit and skill at determining events, only to bring us up short when we realise it is precisely those qualities that have secured the Empire and prevent the island inhabitants from reaching true freedom. A kind of Marxist spaghetti western, it’s earthy, vital and disturbing all at the same time.

19. From What Is Before (Lav Diaz)

At six hours long – and that’s without an interval – this magnum opus is a forbidding prospect to even the most adventurous cinephile. Which may be why, even after the unprecedented success of Diaz’s Norte, The End Of History, it was released hardly anywhere, and one of the greatest films of the last decade got missed.

A portrait of a remote Filipino village during the onset of the Marcos years, its gradual revelations of duplicity and scaremongering among the locals in order to set the foundation for an incoming regime are complemented by the slow reveal of figures emerging from landscapes held in long shot and the audience’s growing understanding of the rural structures being torn apart.

Seldom has a film shown with such quiet fury and concentrated intelligence how political power disturbs and manipulates populations even at the most basic level for its own gain, and leaves shattered lives in its wake.

20. The Sun (Alexander Sokurov)

And finally, imagine if, years from now, critics attempted to choose one film to sum up the whole of the 20th century; they may bypass the obvious choices of today, like The Godfather or Citizen Kane, and instead go for Alexander Sokurov’s The Sun.

A modest portrait of the last days of World War Two, seen from the point of view of the Japanese Emperor Hirohito holed up in a bunker in his Imperial Palace, it depicts both the militarism and the crazed cult of obedience found in so many political regimes of the century, but also the loneliness and fragile ineffectualness of the man at its centre, who, in his inability to fully comprehend the forces unleashed around him, comes to represent all of those who suffered the consequences of these regimes, whether as leaders or followers.

The film ends with one of the most beautiful shots in recent memory, of the dawn coming up over a shattered Tokyo, an epitaph for what has been destroyed, but also a ray of hope for the future.

Author Bio: Mike is a freelance film writer, currently living in London, who has written for the BFI Screenonline database, Moviemail and horror movie site, Zombie Hamster. He also subtitles TV and films for the hearing-impaired and prepares audio description for the blind.