7. Brightness (Souleymane Cissé, 1987) – Mali/Burkina Faso/France/West Germany/Japan

Weirdness of the tribal kind

Metaphysical fairy tale Brightness (Yeelen) is considered the most attractive African film, even amongst the critics skeptical about Cissé’s storytelling skills. Based upon Mali oral legends, it takes us back to XIII century and brings a mystical narrative of maturation and spiritual journey of Niankoro, who’s compelled to face his own father, evil shaman Soma.

The process of the youngster’s initiation and the attempts of preventing it from happening are depicted side by side, whereby the final showdown is equated with the primeval struggle of creative and destructive forces. Insurmountable generation gap is presented as one of the main causes of violating the vital and cosmic balance.

Cissé accepts the ancient myths’ cyclic structure and composes a meditative ode to nature and people. He entrusts the roles to nonprofessionals, who should be credited for the characters’ authenticity and the film’s immediacy. The primitive beauty of the tribal culture portrait is credible and, for the Westerners, quite exotic and mysterious.

8. Oh, Moon! (Reha Erdem, 1988) – Turkey

Weirdness of the tame kind

Allegorical drama Oh, Moon! (A ay) is Reha Erdem’s feature debut as well as a fine showcase of his lavish talent. Poetic and mystified like some distorted fairy tale, it recounts an unusual story of growing up, facing the realities and accepting the burden of the past.

Yesim Tozan plays a parentless 12-yo Yekta, a girl of vivid imagination living in a spinster aunt’s home, alongside a paralyzed grandfather and a domesticated seagull. Not wanting to lose her childhood freedom to social norms, she persistently resists the grown-ups boarding school plot.

Erdem’s cinematic, cliché-defying language is not always understandable, yet his representation of Yekta’s dreamy world is fascinating. A hypnotic atmosphere is achieved via the shadow play in B&W imagery, Vivaldi’s vivacious compositions and the shooting locations advantages. He’s particularly fond of the spooky house interiors and the monastery ruins, where Yekta meets (or imagines?) enigmatic, one-eyed old man, the only person who understands her.

9. Bo Ba Bu (Ali Khamrayev, 1998) – Italy/Uzbekistan/France

Weirdness of the non-verbal kind

French actress Arielle Dombasle plays a mysterious woman, who appears “out of nowhere” in a Central Asian wasteland. Lost, exhausted and amnesiac, she is discovered by a middle-aged shepherd Bo, who takes her to his modest hut, which he shares with his brother (or son?) Bu. She is named Ba (of course!) and taken care of, but soon it becomes clear that their life together is doomed.

Under the hijab of a “mute” ménage à trois drama hides the pichoq sharpened to cut through the bigotry, backwardness, government corruption and complete isolation from foreign influence. Ali Khamraev criticizes the objectification of women as well, thereby adding a universal dimension to his film. A little jaunt to a “civilized” world reveals an evil greater than the desert mistreatment, so it’s no wonder Ba returns to the ostensible safety of her new home.

Spiced up with a bit of humor, this provoking story is told in gloomily exotic pictures of ramshackle objects, livestock and snakes, whereby all the talking is replaced with grunts and groans. A dominant color of sand and wilted plants accentuates the passive heroine’s frailness.

10. Away with Words (Christopher Doyle, 1999) – USA/Japan/Hong Kong/Singapore

Weirdness of the granny-rapping kind

Starring Tadanobu Asano as a young synesthete, who sees ‘31’ as a ‘broom’, Christopher Doyle’s directorial debut is reminiscent of a deep blue confusion in a crimson dusk or a strawberry-flavored candy on a jaundiced leaf. It feels like walking through the labyrinth of jumbled thoughts, inexplicably relaxing. It smells like milk sugared with the childhood memories. It grabs you and pushes you down the endless slide…

Anarchically directed, this comic and “autistic” art-drama could be dubbed as the picture book of dreams and mnemonic associations. As the title suggests, the words are of least importance, which is fine in a tale about the impossibility of communication.

Away with Words (aka San tiao ren / Kujaku) also chronicles the quest for a safe haven and the people amongst whom one might wake his/her real self. Maybe it’s all about something else, but who can tell in the unstoppable stream of saturated colors, with oneiric melodies flying above?

Narratively off-beat, this little flick seems like a nude of the eccentric, yet lovable protagonists’ state of mind. And it’s as wonderfully gaga as a DJ granny.

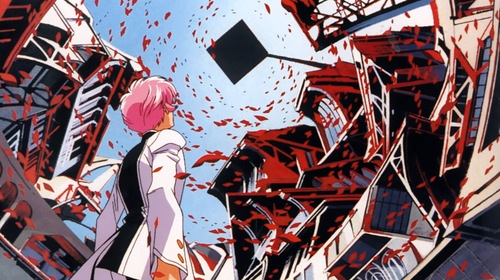

11. Revolutionary Girl Utena: The Movie (Kunihiko Ikuhara, 1999) – Japan

Weirdness of the anime kind

A room gets swallowed by the vortex of sheets. A girl transforms into a cabbage butterfly. A funny game is played between a cow, a mouse and the elephants. Lotte Reiniger’s silhouette works are referenced. The myriad of rose petals, accompanied by hair fluttering, fly in the wind. Each and every sequence thereof is beautifully animated, but none of them is as bizarre as the futuristic car wash metamorphosis which precedes the end.

Under the burden of pulsating metaphors, the enigmatic narrative melts like the sweetest of many-sided nightmares. Is it a coming-of-age or the loss of innocence allegory? A bold display of human obsessions and hidden desires? Or a psychosexual drama that takes place in some schizophrenic’s imagination? One thing seems certain – at the core lies a lesbian romance of heroine Utena and her “rose-bride” Anthy, who are both striving to get out of their own subconscious hell.

Ikuhara’s postmodern fairy tale, with archetypal characters and metaphysical dimensions, is surprising, challenging, seemingly nonsensical, brutally surreal and artfully directed. And it’s influenced by the Machintosh’s architecture, as well as Escher, de Chirico and cubist paintings.

12. Fragile As The World (Rita Azevedo Gomes, 2002) – Portugal

Weirdness of the gentle kind

Named after a verse from Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen’s poem, art drama Fragile As The World (Frágil Como o Mundo) is as romantic as Romeo and Juliet. With its high cinematic value it can be comfortably placed between Antouanetta Angelidi’s and Tarkovsky’s films.

A lyrical story of Vera and João, who can be together only in death, is built upon predominately B&W, chiaroscuro images of gentle and sublime beauty. Reduced dialogues are pushed into the background. Azevedo Gomes narrates in the rhythm of solemn silence, as if wishing to grant more time to the young lovers. Her feature is divided in two acts – the first one is rooted in “outré” reality, whereas the second is rendered as elegiac fairy tale.

And love is tame as two protagonists – born from the fear of pointlessness, it reminds us of losing oneself in a moment, as well as of everything they’ve forgotten in the fog-veiled forest. However, it’s powerful enough to wake the ghosts of the past and color the world which solely belongs to Vera and João, who are wonderfully portrayed by nonprofessionals Maria Gonçalves and Bruno Terra.

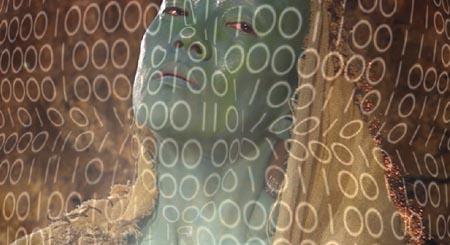

13. Vera (Francisco Athié, 2003) – Mexico/USA/France/Germany

Weirdness of the transcendental kind

On the spiritual level, mind-tripping Vera is akin to Jodorowsky’s Holy Mountain, Oshii’s Angel’s Egg or Hussain’s Ascension. An inspiring and enlightening is the adventure Athié takes you on.

The film recounts an old man Juan’s dreamlike journey, which might be his hallucination of what precedes life or, most likely, a meditation on passing over to the other side. Inspired by Mayan traditions and Christian beliefs, Athié merges these two disparate aspects into the esoteric One.

The protagonist’s guide is a green-skinned Goddess (butoh dancer Urari Kusanagi, convincingly divine and ethereal), who’s born from the cosmic skim and dances with a little skeleton at one point. Marco Antonio Arzate’s Juan is depicted as a patternal figure, an ordinary man faced with the inevitability of mortality. They mostly communicate in a body language, given that the dialogues are reduced to bare minimum.

Shot in Yucatán mountains and caves, Vera is visually impressive and not even the outdated special effects ruin the magic created by the fascinating locations. On the contrary, CGI is nothing more than a supplement, not the main attraction.