Part III of the cinematic weirdness shifts focus in favor of the Japanese films which occupy one quarter of the list. However, there is still enough variety to accommodate different tastes, from avant-garde through animation and all the way to postmodernism.

1. Silence Has No Wings (Kazuo Kuroki, 1966) – Japan

Weirdness of the fluttering kind

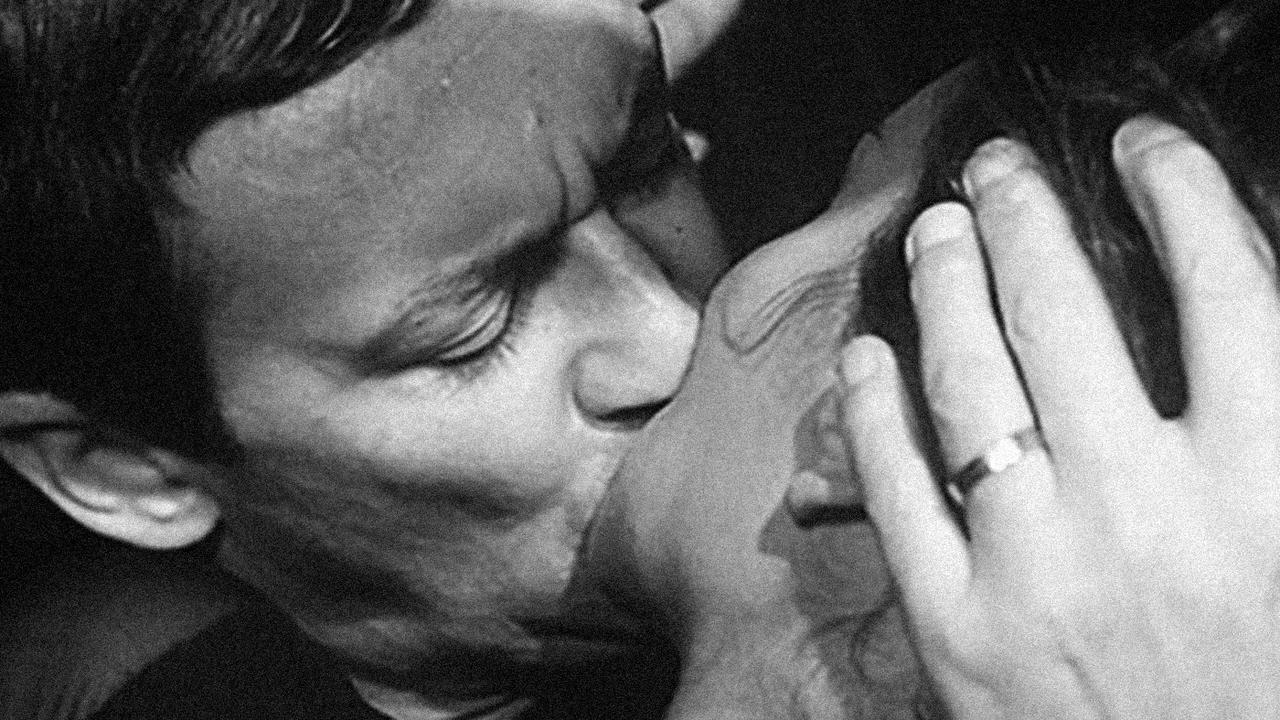

Carefully following the Great Mormon (Papilio memnon) metamorphosis on the way from Nagasaki to Hokaido, Kazuo Kuroki explores post-war traumas and the identity crisis of his own nation. The themes of filmmaking issues and societal revival, with political machinations in their background, are also being considered.

Silence Has No wings (Tobenai chinmoku) begins and ends with a capture of the aforementioned butterfly who’s symbolically represented by adorable Mariko Kaga. At first, she appears as an angel, in a white dress and shrouded in fog, whereas in the epilogue, she wears black, embodying death and/or mourning the victims of nuclear attacks.

Her presence is crucial to each and every segment of the fragmented story that focuses on several psychologically unstable protagonists who are striving to solve life’s many a puzzle.

Along with Kuroki’s precise direction and Kaga’s brilliant performance, praiseworthy are elegiac theme, cacophonous soundscapes (kudos to Teizō Matsumura) and DP Tatsuo Suzuki’s gorgeous B&W imagery – often shot from the caterpillar’s perspective.

2. Garden of Delights (Silvano Agosti, 1967) – Italy

Weirdness of the matrimonial-hell kind

In his feature-length debut, Silvano Agosti brings an edgy anticlerical attitude and exposes the negative consequences of bourgeois-Catholic upbringing, all while under the influence of Bergman and Nouvelle Vague. As the epigraphs for the ensuing chapters, he utilizes the details from Bosch’s famous triptych, hence the title.

The author puts himself and the audience in the place of (anti)hero Carlo whose first wedding night at the Italian Riviera hotel turns into a stifling nightmare – his wife Carla is pregnant and he didn’t want to get married in the first place. Carlo’s contempt towards the “holy matrimony” leads to an adultery which only intensifies his anxiety.

From the narrative grounded in a constant interweaving of oppressive reality with invasive dreams and recollections emerges a provoking, iconoclastic psychodrama with dense, ill-omened atmosphere. One of its most striking scenes is the vision of a wedding ceremony that looks like black mass overture – a clear mirror image of Carlo’s gamophobia.

Also memorable is the “insolent intermezzo” that juxtaposes a rock party and the altar servers procession. And it’s hard to forget Carla’s helpless and, at the same time, reproachful look in the final shot. Equally remarkable are Aldo Scavarada’s elegant and evoking cinematography and Enio Morricone’s discrete score.

3. Trails (João César Monteiro, 1978) – Portugal

Weirdness of the folkloric kind

At the beginning, a maiden meets a youngster and says: “Let me guide your dreams.” He silently agrees and they both take an uncertain path…

There’s a great possibility that it is Monteiro speaking through her words, while taking a viewer on an unpredictable journey. From the perspective of a mildly cynical poet who’s inspired by his nation’s oral traditions, he creates a rhymeless yet sublime poem which is bursting with symbolism.

Simultaneously, he delivers an ethnographic documentary on bizarre customs from the Portugese province Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro and a medieval legend of Branca-Flor on the run from her demonic father. Near the end, he even takes us to the XX century, to the estate of a ruthless oligarch, and all the storylines are linked by the quotes from The Eumenides.

In that manner, three mythologies are interlocked – Greek, Portuguese and Monteiro’s personal one. Reality and fantasy / life and death become one as the multilayered narrative glides gently backward and forward within that unity.

And with many masterly composed scenes of rustic beauty, Trails (Veredas) often recalls Parajanov’s admirable tableaux vivants.

4. Gwen, the Book of Sand (Jean-François Laguionie, 1985) – France

Weirdness of the phantasmagoric kind

In the desert, the Gods have left behind a luminous entity Makou, which has been releasing giant replicas of everyday objects for many nights. However, the nomads inhabiting that infinite space are completely oblivious to the real purpose of those “gifts”, so they utilize them in different ways.

Driven by curiosity, a fearless 13-yo girl Gwen and a mute boy Nokmoon leave their dwelling to get close to the mysterious light, but Nokmoon is taken away by Makou. Accompanied by his grandmother Roseline, Gwen goes on a quest to save her friend.

Watching Gwen, the Book of Sand (Gwen, le livre de sable) is comparable to reading parts of One Hundred Years of Solitude, while enjoying Dalí’s art and trying to catch a glimpse of The Savage Planet. Laguionie’s animated film carries ambiguous meanings, probably rooted in religion and/or philosophy, and as such it is quite a treat for the fans of bizarre and surreal fantasies.

Gwen’s adventure is quiet, gentle, elegant and unhurried, supported by intoxicating melodies and mesmerizing imagery of predominantly warm colors. At its end, you’re left with a question: “Was it all just a pleasant, sand-covered reverie?”

5. Topos (Antouanetta Angelidi, 1985) – Greece

Weirdness of the feminine kind

For her phantasmagorical (anti)drama Topos (literally translated as The Place), Angelidi uses chiaroscuro as effectively as the masters of the Renaissance. Inspired by the works of de Chirico as well, she creates the astonishing kaleidoscope of saturated colors and almost abstract sets where the peculiar action takes place.

The life of a dead heroine (Anna?) is depicted as a game played by cryptic rules in the illusory space, which might be a surrealistic version of her household, and outside the flow of time as we know it. Resurfaced fragments of her deeply buried recollections are transformed through the prism of dream logic and built into a twisted narrative structure. Anna’s spirit possesses her mourners, so their words become the projection of her own stream of consciousness.

To understand the hermetic story, you would have to hear “the voice of Death” which is mentioned by one of the “vessels” of Anna’s soul. The movies’s archetypal characters are mostly women – emotionally empty, they are elegant marionettes in a mechanical ballet of perplexing juxtapositions.

6. Book of Days (Meredith Monk, 1988) – France/USA

Weirdness of the anachronistic kind

Tackling the issues of time(lessness), as in her debut short Ellis Island, Meredith Monk leaves her comfort zone and creates a work of everlasting beauty and of high aesthetic value. Book of Days begins with modern construction workers breaking the massive wall and revealing a medieval European town behind it. As soon as the women in dark robes leave their houses, a winding cobble-road is brought to life…

In the course of unconventional story, mysterious querists interview several characters, asking them questions which they can not answer – What is a radiator? Are you an athlete? Is the Earth flat or round? Whether they were erudites or farmers, the people from the past were confused by the concepts which were not (scientifically) defined in their era. But, there are two exceptions – mute, ostensibly bonkers homeless-lady, wittily played by the author herself, and a little girl whose visions and drawings foreshadow the future.

The quasi-documentary segments are not sole “disruptors” of the Middle Ages. There is also a postmodern performance on the square and a dance of death which mimics the plague spreading, all framed with great precision and sprinkled with Monk’s intoxicating wide range vocals.