7. Son of the White Mare (Marcell Jankovics, 1981) / Hungary

Weirdness of the fairy-tale kind

Allegorical fantasy Son of the White Mare (Fehérlófia) is one of the most impressive evidences of Marcell Jankovics’ wizardry. Rooted in nomad tribes legends, it touches on the topics the Hungarian author is usually concerned with, such as a fairy-tale symbolism, comparative mythology, sacral art, ethno astronomy, religious and popular beliefs.

It follows the trials and tribulations of a young man, born of a white mare and adorned with superhuman strength, in a cyclical and universal story. Relying upon hyperbole and numerology, it contains recognizable motifs, such as unintentional release of evil force. Before rescuing the three princesses from their monstrous captors, a titular hero must face a mischievous dwarf with a magical beard, as well as a gryphon who has to eat twelve oxen and drink twelve barrels of wine, amongst the other obstacles.

Narrative elements and conventional structure are implemented in an unusual way, whereby the modern and the traditional constantly intertwine, tear or supplement each other. Via a healthy dose of humor and irony, and driven by dream logic, Jankovics speaks of trust, bravery and determination, while communicating an anti-war message and pointing out the negative aspects of computerization.

His precise direction is accompanied by top-notch voice-acting, outlandish mix of space rock and electronica and mind-blowing visuals. Fehérlófia is like a fluorescent tapestry, that comes to life with all of its vibrant colors, pulsating textures and elusive shapes.

8. The Forest Song. Mavka (Yuri Illienko, 1981) / Soviet Union

Weirdness of the mythological kind.

Arthouse fairy-tale The Forest Song. Mavka (Lesnaya pesnya. Mavka), a loose adaptation of Lesya Ukrainka’s play, could be comfortably classified as one of the most unusual Soviet flicks.

Following Parajanov, whom he worked with as a DP on Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Yuri Illienko turns to the past and spins his own version of a tragic-romantic tale of a titular forest nymph. Mavka falls for a young piper Lukash and appears before him, in spite of her “brothers and sisters” warnings. Their love is born in spring, ripens through summer and dries during autumn, and in winter, she desperately tries to breathe life into its rotten corpse.

Don’t let the breezy “hippy” prologue fool you – as the narrative progresses, The Forest Song becomes gloomier, which is reflected in the heroine’s looks, a mirror of her soul. Illienko’s dialogues are sparse, but he is brilliant at portraying what’s invisible to the eye, using the language of symbols – water, leaves, fire, fog, snow, rocks, wheat…

His exquisite visual compositions are drenched in mystery and melancholy, often in saturated colors as well, evoking the spirits of the ancient Slavs, through the symbiosis with ethereal score.

In a lyrical story, he presents all the humans as antagonists, accentuating their inability to achieve perfection, i.e. to understand the divine. The empathy is redirected towards supernatural entities, presented as mystical, esoteric and modern at the same time. Pure magic.

9. Karagoez catalogue 9.5 (Angela Ricci Lucchi & Yervant Gianikian, 1983) / Italy

Weirdness of the documentary kind.

Swimmers. Japanese woman. A masquerade. Penguins flock. Underwater fauna. Exotic dancers. Naughty girl. Laboratory experiment. Turkish shadow theatre… These could be the titles of micro-chapters that form the silent docu-fantasy Karagoez catalogue 9.5 (Karagoez catalogo 9,5, with the number representing the tape format).

It is a 45-minute long and completely silent anthology of archive footage from the early XX century, found, slowed down, edited, tinted and transformed into a fascinating film-mosaic by a painter Angela Ricci Lucchi and her partner, the architect Yervant Gianikian.

The directing duet explores facial expressions, figures and movements of their “protagonists”, takes us back to the time when the seventh art was in its infancy and allows us to peek into the most hidden corners of life in those days. Magical in their “outworn” beauty, seemingly unrelated images form a sort of an associative chain, that doesn’t break at the sudden end, but extends to infinity.

It is not quite clear whether there are some hidden meanings to it or if the helmers are interested in gestures and physiognomy only, but that doesn’t matter much, given that Ricci Lucchi and Gianakian leave a lot of space for contemplation.

10. The Pointsman (Jos Stelling, 1986) / Netherlands

Weirdness of the (pseudo) romantic kind

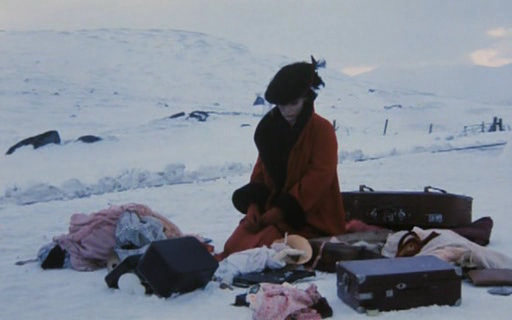

In the middle of nowhere, a well-groomed lady gets off the train and meets an unsophisticated pointsman, the only man to be found around. Her disgust and arrogance, as well as his unkindness and disinterest metamorphose into something akin to love.

A cryptic depiction of the two strangers and their odd relationship is characterized by twisted humor and almost complete absence of dialogues, compensated by strong physical presence of the starring Stéphane Excoffier and Jim van der Woude.

Nameless protagonists couldn’t be any more different, but for that very reason, they are a perfect couple in the world built upon a dream logic. Van der Woude reminds of a deadpan combination of Charlie Chaplin, Jerry Lewis and nonprofessional actor from some East European rural drama, while Excoffier looks like a classic film-noir femme fatale. Their romance seems impossible and yet, as it develops, sexual tension between the beauty and “the beast” intensifies, becoming more obvious and destructive.

The growth of their passion’s flame is stressed through the use of red color, which portends blood-spilling epilogue. Three more men appear, one of them being the pointsman’s rival, changing the dynamics of this minimalist and bittersweet dramedy in the process. And the sleepy scenery of Corrour railway station (in Scotland), where the shooting took place, plays the part of a remote and preposterous land.

11. Mirror of the Planet (Jytte Rex, 1992) / Denmark

Weirdness of the Aleph kind

Inspired by Borges’s short story The Aleph, experimental drama Mirror of the Planet (Planetens spejle) is a blurred portrait of a fictional astronomer Adam Morgenstern. Fragmented narrative about everything and nothing seems like a continuous stream of consciousness, dreams and hallucinations of the protagonist, who is trying to grasp the eternity and return to pristine darkness, only to become the (voluntary?) prisoner of one point of his (non)existence.

Jytte Rex identifies a futile quest for the secrets of the universe with the process of facing the fear of death, blurring the borders between the tangible world and the abstract realm. Via poetic monologues and philosophical dialogues, as well as meditative declamations of a mysterious Heraldess, she raises many questions, but leaves you – mesmerized – without the precise answers. On a steep road towards the ultimate truth, she is accompanied by a Danish literate Asger Schnack, as co-writer.

Rex’s painter sensibility is mirrored in every frame, while she and her characters strive to discover whether life goes on behind black holes, dubbed as “the presence of the God’s absence” by one of Adam’s colleagues. Architectural elements are treated as metaphors and the space they define becomes the meeting place for the rational and the spiritual, the meaningful and the nonsensical.

12. The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb (Dave Borthwick, 1993) / UK

Weirdness of the eeky kind

Tom Thumb, a bald boy with a fetus-like head, is a product of an accident caused by an insect in artificial insemination factory. Wretched as he is, he’s accepted and loved by his parents, but their “painful joy” is short-lived. The government’s agents take him away to Laboratorium, a science institute for experimenting on the “freaks of nature”, eliminating Mrs. Thumb.

Helped by a mechano-reptilian creature, Tom reaches a settlement built on a landfill and inhabited by miniature people. Their leader, an occultist Jack, assumes custody over the tot and tries to reunite him with his father, who finds solace in a local pub.

As the title implies and synopsis confirms, Dave Borthwick takes lots of liberties with adopting a famous folk fairy tale. Borrowing from the legends about Jack the Giant Killer and drawing inspiration from Kafka’s writing, Švankmajer’s animations and Lynch’s Eraserhead, he delivers a dark, cruel and dirty fantasy with heavy and sticky atmosphere.

Replacing the dialogues with growls, groans, mumbles and only a few understandable words, he narrates through a nightmarish imagery of a discomforting, mutant-filled world.

13. The Roe’s Room (Lech Majewski, 1997) / Poland

Weirdness of the autobiographical kind

Even within the constraints of a low-budget TV production, Majewski achieves miracles. Film-opera The Roe’s Room (Pokój Saren) focuses on his memories of adolescence, poeticised and split into four seasons, all marked with death’s presence.

Working not only as a director, but librettist and composer as well, he turns the scenes from everyday life into a stupendous ceremony. What initially seems like an ordinary drama, save for the unconventional approach, slowly transforms into an inspired work of magical realism.

A water flows from the tabletop; the walls crumble and bleed; a tree grows and flourishes in the middle of the apartment. Religious allusions and ambiguous symbols are interwoven into a tale of life’s cycles and transience.

Deep shadows of de Chirico reproductions, serving as decor, are the perfect counterpart to mystified semi-darkness of mother, father and son’s daily routines. Macrocosmic changes happen in the microcosm of their home. Deliberate camera movements make dreamlike and melancholic pictures from Majewski’s altered past to remain in your memory long after you’ve seen them.