9. Gimme Shelter (1970) – Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin

A decade of popular music festivals saw the release of a few major documentaries chronicling rock music and hippie culture in the 1960s.

D.A. Pennebaker made Monterey Pop in 1968, Michael Wadleigh (along with Martin Scorsese) produced the epic Woodstock in 1970, but the brothers Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin took their documentation of the controversial Altamont Free Concert and turned it into one of the most shocking documentaries ever made, producing what many call a swan song for American youth culture. That film was Gimme Shelter.

With their trademark direct style of documentary filmmaking, Gimme Shelter chronicles the Rolling Stones’ 1969 tour that culminated in the Altamont show which left four dead with one directly linked to the Rolling Stones themselves, the controversial security provided by the Hell’s Angels, and the uppity and aggressive hippie crowd.

The masterful film captured a dark side of American youth and pop culture that sent shockwaves through what was perceived as a glorious era for independence and artistic liberty.

The film’s unfolding of a clash between counter-cultures escalating into madness is captured unflinchingly by the Maysles’ camera, culminating with the shocking death of Meredith Hunter who was stabbed after pulling a gun out while the Stones were playing.

Suspects involved are the concertgoers, the Hell’s Angels providing security, and the bands themselves, most notably the Rolling Stones, who despite their pleas for peace among the crowd, became a hyped publicity machine after the concert’s tragic events.

Amping the tensions of Vietnam fear, the Manson family, the death of peace and love, Gimme Shelter plays out like an angry and aggressive horror film where no one is safe and the decline of American culture unfolds before our very eyes.

10. M*A*S*H (1970)

In the midst of America’s involvement in Vietnam, Robert Altman’s satirical comedy about Korean War surgeons became yet another outspoken piece of cinema critiquing America’s involvement overseas.

Following three insubordinate military doctors, M*A*S*H transposes the carefree hippiedom of the 1960s onto the 1950s Korean battlefront. Rather than focus on combat, the camera instead turns its eye to those saving lives.

Not willing to succumb to the political and methodical ways of their superiors, the three surgeons instead enjoy drinking, sleeping around, and partying, much to the chagrin of their superiors. While disrupting the militaristic order of things, the three also show lots of heart and acknowledgement for their fellow man, helping soldiers with problems and even save the life of an American Congressman’s son.

The first in a series of Altman films that twisted the forms of genres, Altman managed to create a lasting impression with M*A*S*H. His take on the war film genre while infusing the story with dark comedy and anti-Vietnam sentiment provided a set up for the popular television series that went into production two years later.

11. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) – Melvin Van Peebles

Before blaxploitation was given a name, two films were made in 1971 that helped kickstart the trend of African-American oppression in America being solved through solidarity and communal support.

Gordon Parks’ Shaft presented an action-oriented plot where the Italian Mob are main antagonists, but it was through Melvin Van Peebles’ bizarre Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song that aggressively spoke out in outrage over the mistreatment of Blacks in America.

After a Black man is killed in a Los Angeles ghetto, the Black community wants justice, and a pair of white LAPD detectives request a local brothel owner to provide a suspect temporarily to please them.

After Sweet Sweetback is chosen, the well-endowed protagonist takes matters into his own hands when he beats the detective senselessly while they attack a Black Panther Party member. Now on the run, Sweetback decides to hightail it to Mexico where he can lay low and eventually “collect his dues” from white society.

Shot on an extremely low budget, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song is not a full-fledged example of New Hollywood Cinema, but rather a reactionary piece of filmmaking made during the era.

Its gritty and corner-cutting style became iconic for the genre that would be synonymous with blaxploitation cinema: The sly and cocky protagonists, devious portrayals of the law, soul-funk soundtracks, and swift but justice-laden violence became the norm and fueled a whole new industry as well as gave the African-American population a cultural and cinematic voice.

12. Deliverance (1972) – John Boorman

In the early 70s a directorial trade-off was made. Hollywood sent Sam Peckinpah to England to make the controversial yet understated Straw Dogs (1971) while England sent John Boorman to the U.S. to direct Deliverance.

Both films dealt with a differentiation is standard action movie style, called the themes of machismo into question, and violently uplifted their protagonists into realizing they are natural born killers. In an era where action cinema consisted of aggressive and racist authority figures (for example Dirty Harry, 1971; and The French Connection, 1971), Deliverance and Straw Dogs managed to turn the action film genre on its head with this scathing indictment of masculinity and action cinema’s overt violence.

Although Straw Dogs has its own stylistic weight, John Boorman’s Deliverance took action cinema to a whole new level. Set mostly outdoors, the film mirrors the sentiments of being pursued and hunted down by an enemy that doesn’t take kindly to outsiders, much like America in Vietnam, and the shocking realization that the bumbling businessmen with different opinions on moral values are capable of murder brings for intense psychological study.

Along with the satirization of the masculine image and its all-bark-no-bite transparency, Deliverance is a fine meditation on the psychology of violence.

13. Mean Streets (1973) – Martin Scorsese

After a couple of low-key films, the world was finally introduced to the style of Martin Scorsese. Much like the obsessive David Holzman from David Holzman’s Diary, Scorsese brought a cinema vérité style unique to himself by immersing autobiographical stories mixed in with over-the-top personalities and pop culture study that started out with Mean Streets.

Following Charlie, a lower-level hood from Manhattan trying to balance his devotion to his Mafia “Family” with his moral and religious ideas amid a life of rough-and-tumble antics with his street friends, Mean Streets tells a story of youthful nihilism and gritty street life that helped pave the way for American crime cinema with an artistic flair.

With a knack for representing his native New York City with the utmost detail, the location shooting and fast-paced writing gives the film an authenticity akin to the Italian neorealists from the 40s and 50s. While serving as a vehicle for Harvey Keitel, who plays Charlie, the one who steals the show is Robert De Niro, who makes one of the most iconic film debuts in cinema history as the wild and unpredictable Johnny Boy.

Along with a soundtrack full of 60s and 70s rock music, Mean Streets set Scorsese up as a stylistic auteur who would go on to influence many independent directors who could trace their inspiration to this very film.

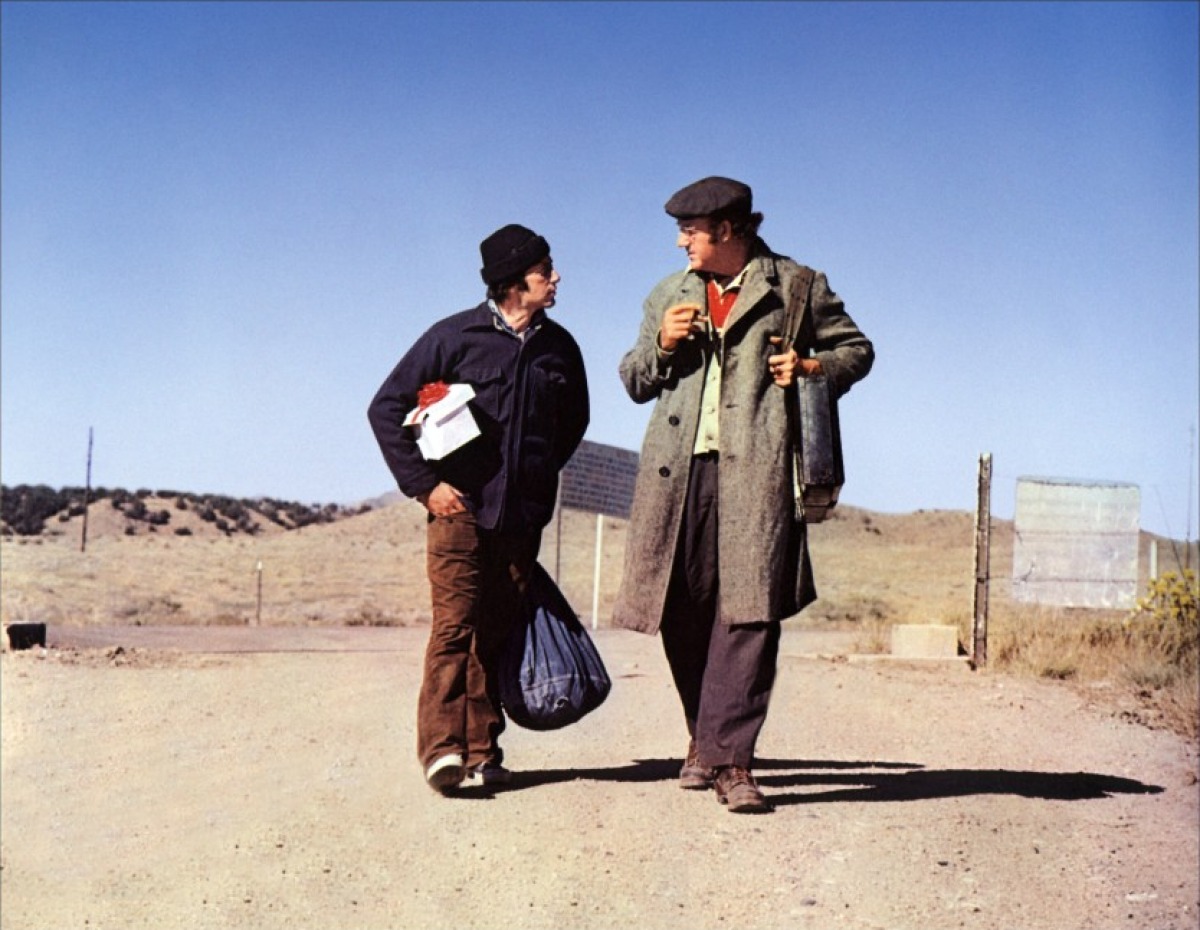

14. Scarecrow (1973) – Jerry Schatzberg

Among the mainstream success of films like The French Connection (1971) and The Godfather (1972), actors Gene Hackman and Al Pacino were already well-established names in New Hollywood. Despite this, both actors speak very highly of their roles in Schatzberg’s low-key tale of hope and friendship against overwhelming odds in Scarecrow.

A road film unlike any other, Scarecrow creates a great contrast of characters through Hackman’s Max and Pacino’s Lionel. Almost like an absurdist Wizard of Oz, two drifters befriend each other and decide to start a car wash business together once they have cleared things up in their personal lives first.

Told like a comedy but with a keen sense of recklessness and despair, Scarecrow tugs at the heart and presents an image of 1970s hopefulness in trying times for various people attempting to make a fortune. With a fantastic script, Scarecrow delivers on the emotional troubles many experienced at the time and did not present a solution, but rather an examination of those undergoing such troubles.

15. The Exorcist (1973) – William Friedkin

After taking New Hollywood by storm with The French Connection (1971), William Friedkin’s next masterpiece took on the supernatural, a far cry away from the hyper-realistic and savage French Connection. The Exorcist’s disturbing nature and bleak unraveling horrified the nation and established itself as one of the greatest horror films ever made.

The film makes comments on the roles of the Church in society as well as the psychological mindsets of those both under and outside the Church’s influence. Set in Washington, DC, The Exorcist also is rife with governmental subtext as well as socio-political comments made on feminism and the role of women in the working world at a time where things were indeed changing.

After a lengthy prologue in Iraq, a Catholic priest with ties to a volatile demonic spirit is eventually called to America in order to exorcize the demon from a little girl.

The girl’s mother, an actress and single-mother experiences a psychological traumatic breakdown at the sight of her only daughter undergoing such a violent transformation while an American priest, struggling with his own faith in the wake of his mother’s death, finds a new calling once he witnesses the evil embodying the little girl.

These four characters expertly represent the eras and mindsets happening at the time, referencing change, fear, and triumph over evil in sheer metaphorical terms. More than just an average horror film, The Exorcist’s denouement is expertly timed and effective in its delivery.

16. Hearts and Minds (1974) – Peter Davis

A year after President Richard Nixon ceased American involvement in Vietnam, Peter Davis made a documentary so startling that it called his allegiance to America into question, divided his audience, and influenced further documentarians with his style and approach.

Being the first “televised war,” Vietnam had its fair share of detractors, and a film like Hearts and Minds definitely aided the anti-war front with its biting critique of America in Vietnam.

Taking footage from attacked Vietnamese citizens juxtaposed with interviews of diplomatic higher-ups, veteran soldiers, and the public, Hearts and Minds does not rely on narration. Much like the direct cinema of the Brothers Maysles (see Gimme Shelter), Davis manages to let the viewer ask their own questions and decide whether the undertakings in Vietnam were justified or mishandled.

Although at the time the film was deemed propagandistic and heavy-handed, the criticism of governmental involvement overseas amid conflict still rings true to this very day as strained international relations shoot to the headlines of our news outlets daily.

17. Lenny (1974) – Bob Fosse

An art film that chronicled an outspoken artist ahead of his time, Lenny is a masterpiece of cinematic form and editing. Telling the story of famed yet controversial stand-up comedian Lenny Bruce, Fosse’s film, shot entirely in black-and-white, hearkens back to a time where moral purity was called into question.

An outspoken representative of the working-class individual, Lenny Bruce fought the system and would often find himself behind bars for obscenity. His crime: Making people laugh.

Played excellently by Dustin Hoffman, Lenny juggles its formal qualities between documentary style and Hollywood drama. Mixed with a series of quick edits or amazingly long takes, Lenny exercises its style brilliantly, all the while commenting on the system’s misunderstanding of its own population.

Although Fosse was more known for his musical theater and musical films, Lenny is first and foremost about Fosse’s main thematic love, show business and its effects on the many who experience it, whether it be the audience, the spectator, or the performers themselves.

The film is brilliant at challenging American policies concerning the right to free speech, blending 1950s and 60s sentiments amid the 1974 mentality furthered by the Watergate scandal and the eventual impeachment of President Richard Nixon, mirrored in Lenny Bruce’s personal war with the law.