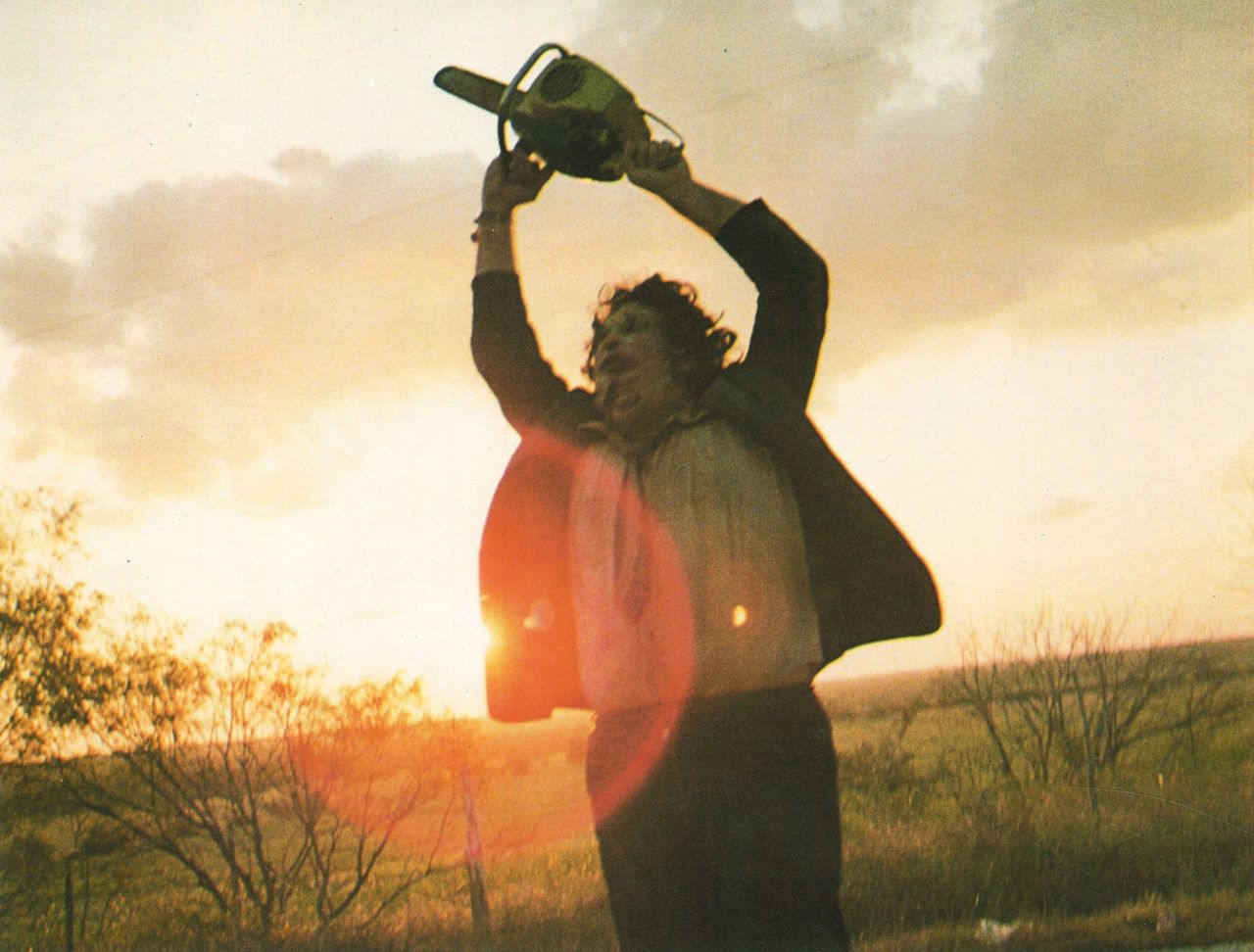

18. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) – Tobe Hooper

Alfred Hitchcock may have brought the slasher film to popularity with Psycho (1960) and Michael Powell raised the cult status of slasher films with Peeping Tom (1960) but the truly disturbing and inhuman slasher villain featuring a villain so unspeakably odd was brought into the limelight with Tobe Hooper’s low-budget and highly effective Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Employing a tactic followed by many horror film directors to come, Hooper’s film claimed to be rooted in fact, making the creepy events of the film all the more chilling. Despite this claim being bogus, the film still holds relevance decades later as a perfect example of horror film pacing and style.

Much like Deliverance (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre explores those who don’t seem to want to be observed, where outsiders aren’t welcome and odd traditions abound.

The film’s small group of teenage protagonists visiting an old family cabin only to be gotten by their curiosity, falling victims to a twisted family of cannibalistic killers, among them the horror icon Leatherface (played by the kindhearted and softspoken Gunnar Hansen).

Featuring grave robbings, ugly sculptures of bones and skin, butchery, cannibalism and a creep factor unrivaled in many horror films since, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre manages to get away with the slasher label while hardly a drop of scarlet is seen gushing from wounds suffered from meat hook, cleavers, mallets, and of course, chainsaws.

An exploration in youth culture and Southern family values, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is one of the best, and most effective horror films ever made.

19. Death Wish (1974) – Michael Winner

While action thrillers were producing icons like Dirty Harry Callahan and Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, out of actors like Clint Eastwood and Gene Hackman, Charles Bronson crept back into the spotlight with Death Wish. An urban renegade tale of a man who loses everything he loves and declares revenge on society.

Much like the conservative action-thrillers of the time such as Joe (1970) and Dirty Harry (1971), Death Wish’s gritty urban setting captured a derelict and wasted New York City landscape that was quite familiar for its time. Junkies, criminals and hoodlums run wild in the streets in both daytime and nighttime, robbing, mugging and killing citizens without remorse.

After his wife and daughter are raped, resulting in the wife’s death, architect Paul Kersey (Bronson) retreats in his sorrow until he is given a contract in Arizona, where he learns to shoot and finds a new lease on life: preying on the scum of the city.

Based a novel by Brian Garfield which condemned vigilante justice, the film instead focused on an embracing of vigilantism, creating a stir among the public over its depiction of violence against minorities by an upper scale white man.

Although the film became an over-the-top action dud with four more installations (all starring Bronson), the original was a controversial and debated film questioning the ills of urban government, policing, social decay, and liberty. Ten years later, the film’s relevance became a focal point once again when a real life act of vigilante justice occurred in similar fashion to the film.

20. Jaws (1975) – Steven Spielberg

The little B-movie that could. By the mid-1970s, the New Hollywood era was at its peak, where the artistically and auteur-driven films being produced were making excellent social commentary and gaining international buzz for its deviation from an industry thought to have gone stale.

However, one film helped shoot the era into an irreproducible time through its economic use of style and fortunate production disasters, making a star of its director and beginning to send the New Hollywood era into a blockbuster-producing machine, an era that New Hollwyood would never regain its footing from. That film was Jaws.

Despite the blockbuster already being in existence with Love Story (1970) and The Godfather films (1972/1974), Jaws sent lineups around the block literally and sent shockwaves among the cinephilic world with its low-key but terrifying story.

Set in a small New York island resort town, the citizens are haunted by a giant shark that preys on beachgoers. Shutting down the beach would mean economic collapse for the town, and despite the new sheriff’s please, the mayor puts his citizenry at risk by leaving the waters open.

A fitting comment on the status of New Hollywood cinema from 1975 onward, Jaws was a masterwork in Hitchcockian suspense and economic use of editing by the extraordinary Verna Fields.

The production’s budgetary concerns and plagued special effects are a success story on its own, proving that less is more as the malfunctioning shark of the film hardly ever worked, leading Steven Spielberg to show less and less of the predatory fish leading up to a tense and gritty final showdown between human and shark.

The success of Jaws led to higher demand in productions focused on effects and blockbuster potential, paving the way for Star Wars two years later. Needless to say, New Hollywood would never be the same again.

21. Nashville (1975) – Robert Altman

Always one for Americana, Robert Altman pulled out all the stops with his take on the musical and social film. Much like the Brothers Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin’s Gimme Shelter (1970), Nashville revisits the music festival setting in the titular city.

Home of the famed Grand Ole Opry concert, Nashville, Tennessee attracts record executives, fans, radio personalities, politicians, and locals alike, uniting them for a week of music and festivities. Altman manages to create a stellar network narrative with multiple perspectives throughout his landmark film, culminating in a final political rally that ends in unpredictability, signalling the end of an era.

Filled with quirky characters, Nashville also contains an excellent soundtrack of blues, country, gospel, and rock tunes written by the stars themselves. The film also manages to break the fourth wall in casting celebrities as themselves within the narrative (in this case Elliott Gould), a trait Altman would employ more blatantly 17 years later with The Player (1992).

Altman’s story direction bringing multiple characters to one location and playing around with the dialogue of his stars, encouraging ad-libbing and improvisation, giving the film a true festive feel. One of the best post-Vietnam social commentary films, Nashville issues an uncertainty towards the direction America would eventually take, and issues a warning that nobody is ever truly safe.

22. Dog Day Afternoon (1975) – Sidney Lumet

No stranger to film by 1975, renowned director Sidney Lumet issued forth a salvo of social anxiety and urban contempt with Dog Day Afternoon. Among one of the angriest films ever made, Dog Day Afternoon tackles certain issues like homosexuality, debt, social injustice, and media representation with such an aggressiveness it has stood the test of time.

Set on a hot Brooklyn day, a bank is held up by three young men, whose motives are made clearer as the film progresses. While an excellent exploration of cinematic time and cathartic acting, Dog Day Afternoon was one of a kind in its style and aggression, fuelling Lumet’s drive for other social satires like Network the following year.

The film’s plot contains many twists right from the get go with one of the robbers ducking out as soon as the guns are pulled; the ultimate twist is made known when it is discovered that one of the main reasons for the bank robbery is for Sonny (played by Al Pacino) to have enough money to pay for a sex change operation for his wife Leon (Chris Sarandon), what follows is a sentimental journey into character exploration that is as heartfelt as it is furious.

23. Taxi Driver (1976) – Martin Scorsese

Yet another social anxiety film, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver is among cinema’s wildest and most well-made films. Borrowing traits from the French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, and Cinéma Vérité, and film noir, Taxi Driver exercised Scorsese’s stylistic traits even further than he managed to do with Mean Streets in 1973.

Focusing on post-Vietnam and post-Watergate confusion, anger, and aggression towards New York City’s dwindling social status and crime-ridden streets seen from the eyes of insomniac Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle (in a landmark performance by Robert De Niro), the film tackles many issues surrounding violent crime, prostitution, conservatism, and political allegiance.

As Travis drives his cab through the nighttime streets of Manhattan, he meets an array of colorful and disturbed characters. Unable to quell the sting of anger and fear, Bickle begins arming himself and ultimately sets his sights on the wrongdoers of society.

The film’s depiction of a scared young man in the big city is effective and evocative of social fears from its time. Featuring music by Hitchcock collaborator Bernard Herrmann and skewed cinematography by Michael Chapman which is equally schizophrenic and distorts the perceptions of reality and what Travis is undergoing internally as well as those who surround him.

24. Sorcerer (1977) – William Friedkin

One of New Hollywood’s most underrated titles, William Friedkin’s Sorcerer is a perfect example of the inevitable blockbuster favoritism which eventually enveloped the era. Released the same year as George Lucas’ Star Wars, Sorcerer did not receive as much press as it could have and has also been labelled as a catalyst for the decline of New Hollywood.

Despite this unfair assumption, Sorcerer is one of the last true New Hollywood films of its kind, where artistic drive was first and foremost in every production only to be overshadowed by bigger budgets and spectacle making way for the effects-laden and spectacular blockbusters that would follow in the next decade.

Essentially a remake on Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953), Sorcerer fits a lot of commentary into its narrative. Faced with the destruction of a refinery in South America, an American corporation attempts to retrieve and transport crates of live nitroglycerin to safety.

The transportation of this ultra-sensitive material is declared a suicide mission, yet the compensation for the job is beneficial to anyone who undertakes the task. The job is passed down to four rough-and-tumble individuals: a Mexican hitman, a Palestinian terrorist, a French extortionist, and an Irish-American gangster whose skills and reflexes are right for the job.

The vibrant cast of characters, slow yet suspenseful narrative, as well as superb cinematography really makes one wonder why this film was so panned by the public and critics as the notions of big business taking over projects with destructive outcomes has been a subject of cinematic discussion for decades to come after Sorcerer was released.

Much like the negative reception of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), Sorcerer has since found its calling nearly 40 years after its release as an important and masterful work of cinema.

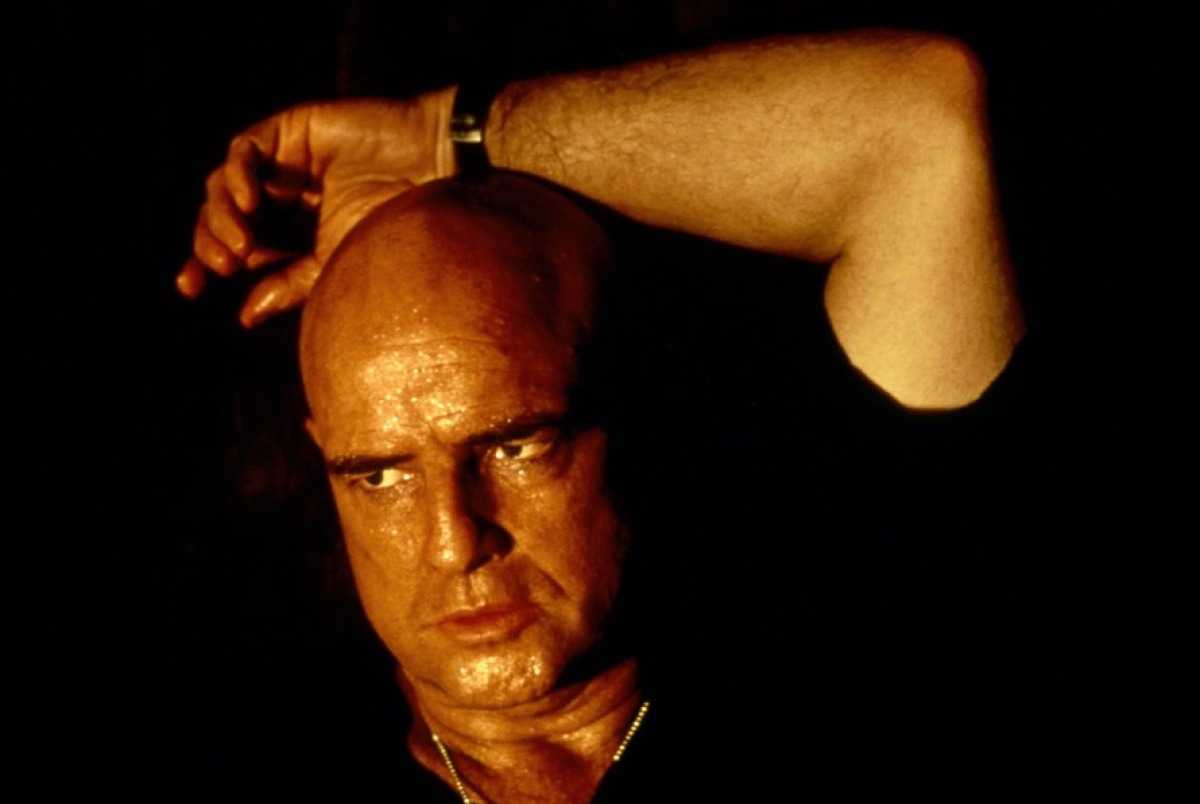

25. Apocalypse Now (1979) – Francis Ford Coppola

One of the last bastions between art and the blockbuster in New Hollywood was Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Echoing post-Vietnam sentiment by setting the narrative in Vietnam itself like The Deer Hunter (1978) while making an anti-war statement like Coming Home (1978), Apocalypse Now relied on heavy artistic expression in its depiction of the horrors of war and the psychological traumas one could experience while being a stranger in another land.

Hired with the task of assassinating a rogue colonel in the Cambodian jungle, Lt. Willard (Martin Sheen) undergoes a crisis of conscience and morality in a long boat journey through warzones, beach heads, and military outposts in order to fulfill his mission. What he finds down the river is an unspeakable inner darkness and terror visited upon the mind and the body for anyone who survives to meet the mysterious Col. Kurtz (Marlon Brando).

Plagued from the start, Apocalypse Now is representative of the struggles of many a filmmaker only blown to an absurd proportion. Over-budget, over-scheduled, uncooperative weather and financial interests, the list goes on, Apocalypse Now proved that the tenacity of directors could overcome the boundaries encountered in ambitious productions.

Along with intense festival success abroad (winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes), it has become an outspoken masterpiece of cinematic genius, with iconic images, chilling performances, and innovative editing techniques in both sound and image from editor-superstar Walter Murch.

Apocalypse Now helped signal the end of an era, which was solidified in 1980 with the failure of Heaven’s Gate and the auteurist hit Raging Bull, as well as a sequel to Star Wars. The era, despite its good run, disappeared in the haze of blockbusterdom.