8. La Grande Illusion (1937)

Jean Renoir had his work cut out for him being the son of one of France’s, and the world’s, greatest painters. He responded by becoming one of France’s, and the world’s, greatest film makers. Many of his films are masterpieces but, to a large number of historians and viewers, his greatest moment is La Grande Illusion (The Great Illusion).

The plot centers on three French soldiers, of differing ranks and civilian backgrounds, who are being held prisoners of war by the Germans during World War I. It’s also a deeper examination of what unites and separates people and why larger differences can lead to war, even though individuals can often find common ground. To this day, this is seen as one of the finest anti-war films, yet, to Renoir’s dismay, two years after its release the biggest war of them all broke out.

9. Olympia (1938)

Speak of the name of German director Leni Reifenstahl and watch the majority of knowledgeable film students react…and not in a good way. While she gets points as being one of the most prominent female directors in film’s history, and one of the very few in the classic era, she was the Nazi’s Third Reich’s favorite film maker (which she later, unconvincingly, claimed was against her will).

She had a tremendous visual sense and often used human beings as part of a larger pictorial pattern. She is best remembered for her infamous paean to Hitler and the Nazis, Triumph of the Will (1934), but her purest, most artistic achievement is Olympia.

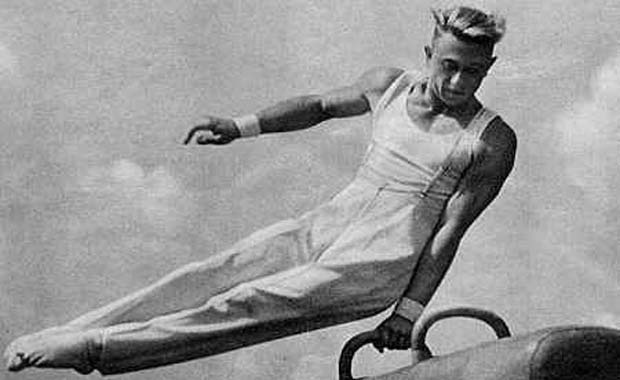

This film was a state ordered recording of the 1936 Munich Olympics. Far more than a documentary, this picture exalts the athlete as she frames the various Olympians in highly stylized and deeply affecting ways. Today such an event would just be shown matter of factly on television but those broadcasts could never match the mythic quality of this film.

10. The Children of Paradise (1945)

The romantic, detailed, deeply and richly emotional The Children of Paradise is the apotheosis of the pre-Novelle Vauge French cinema. This is somewhat unusual in that it might be termed a sui genesis film. The directing-writing team of Marcel Carne and Jacques Prevert had made some notable films before, as had some of the actors, but nothing on this level and none of the artists involved would rise to this level again.

The story, set in a colorful, crime-leaning section of 19th century Paris, involves the intersection of a number of disparate characters, four men in particular, with a most beautiful, enigmatic and self-willed woman at the center of the story. Exquisitely crafted, this is one of the great treasures of world cinema.

11. Paisan (1946)

Living in strife-torn World War II era Italy was surely no picnic and it is a testament to the human spirit that anyone would want to or could even find a way to create films in such an environment, especially making films which meaningfully comment on the highly dramatic times.

Making these films in the conventional manner wasn’t possible due to the lack of funds and materials such films in that style would involve, not to mention that these films wouldn’t accurately reflect the situation. Thus, the young Italian film makers of the day used whatever scraps of film stock they could salvage, filming in real locations with natural lighting for the most part, and mainly using non-professional actors in the cast.

One of the most prominent of these film makers was the intellectual Roberto Rossellini and one of his premiere achievements, and one of the best remembered films of what became known as the “Neo-Realist” movement, is Paisan.

The pictures is an omnibus consisting of seven episodes related only by the fact that they convey the history of the last days of the war in Italy through the eyes of the people at ground level and show that ,even at its end, war brings nothing but misery and bitterness. This film and the movement it represents would influence young film makers until this very day.

12. Spring in a Small Town (1948)

Largely due to the fact China was so isolated from western culture for so many years and that, for decades, western based film histories were Hollywood and Euro-centric, Chinese cinema was rather little known in the west for a lengthy time. This was quite short-sighted since, with the country’s large population, a successful Chinese film would end up as one of the most viewed films in cinematic history.

A key discovery of Chinese, and world, film history, is this much acclaimed film (in the modern day, at least). Set just after World War II, the film concerns a family who has been left physically intact but devastated by the war. The father can only dream of what once was and he and the wife share a relationship now devoid of love but deep in caring and responsibility for one another and their daughter.

However, a family friend/old flame from very long ago comes into the picture and challenges the wife’s sense of priorities. This was the final film of director Fei Mu, who had been a major force in Chinese films of the pre-Mao era. However he and this decidedly apolitical, and deeply sensitive, film were look upon without favor in the new age and his career was ended while this film had to wait for a new day to be appreciated.

13. The Red Shoes (1948)

The British film making team known as The Archers (director Michael Powell and writer Emeric Pressburger) were unique to say the least (and, in their own time, would not say who contributed what to their films). Every film they created was utterly unto itself in both originality and in relation to other films in the makers’ cannon.

Through certain themes ran throughout their work, they never repeated themselves. The high point of their careers (and, though an odd set of circumstances, their ultimate undoing) was the ballet themed film The Red Shoes, a huge worldwide hit (though less so in the U.K, strangely enough).

This is a very simple tale of a beautiful and brilliant young ballerina (actual ballerina Moira Shearer, giving a surprisingly professional performance) tragically being forced to chose between the love of a young composer (Marius Goring) and love of her craft, exemplified by her ultra-demanding ballet impresario (a superb Anton Walbrook).

The glory of the film lies in its amalgam of choreography, editing, use of color in sets, costumes, and scenery, and in the compelling way such a plain tale is turned into the fanciest of valentines to the world of dance (and virtually EVERY dancer since the time of this one’s release knows it well).

14. Los Olvidados (1950)

Luis Bunuel was, perhaps, the greatest surrealist film maker in the medium’s history (though there are other worthys, to be sure). However, his career was nearly destroyed at the start when the Spanish government joined with the Catholic Church to take extreme umbrage at 1930’s L’Age d’Or to the extent that Bunuel was banned from film making…for life!

He left the country and went to Mexico and managed to find work in the Mexican film industry (though not as a director) for almost twenty years until he was able to start directing in what was then considered a backwards, unnoticed, minor film market (all the better not to be seen).

Though some of his Mexican films wouldn’t reach the heights of the films of his eventual return to Europe (which the earlier films made possible), there were still some truly great ones in the mix.

Perhaps the best of them all is this film, a pitiless study of juvenile delinquency set in the slums of Mexico City. While such a similar film made in Europe or, especially, Hollywood, at the time would have probably had sentimental and/or preachy elements, this film spares no one and nothing. The society that creates these juvenile monsters is bad, but so are they and the director-writer’s surreal elements only increase the level of discomfort, right up to a jaw-droppingly bleak finale.

15. Summer with Monika (1953)

Swedish writer-director Ingmar Bergman is truly one of the seminal figures in film history, thanks mainly to his deep thoughtful and philosophical films which probe the human condition, often centering on humans coping with moments of believable despair.

Many of his greatest films might be a bit obscure or difficult for newer, younger viewers, so a good starting point with Bergman for that viewer might well be a lesser known film which would be much more identifiable.

Summer with Monika tells a simple tale. Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson, at the beginning of a successful career, often paired with Bergman) meet while working at the same dull place. Harry is dependable but rather lax and unexciting while Monika is full of life to the point of being wild. She persuades Harry to steal his father’s boat and the two set off for a summer together on the Swedish coast. Their sexually frank journey ends in a manner that won’t surprise more mature viewers but may well give younger ones pause for reflection.