16. Ugetsu Monogatari (1953)

After World War II, it came as a revelation to many in the West that Japan A. had a film industry and B.that the films made in that country could rank among the best anywhere. One of the most prominent of the generation to break through internationally was Kenji Mizoguchi.

A sad irony is that this fine director had actually been working at film for some thirty years when he gained recognition in the early 50s and had only a few more years of career and life left to him at that point (though posterity has been kind). Of his masterpieces, perhaps the supernaturally tinged war story Ugetsu Monogatari might be the most arresting to modern younger viewers.

During a war torn time in Japan’s long Feudal age, a potter and his neighbor, who wishes to become a samurai, go looking for wealth instead of focusing on their families’ safety. The two are lured into deceptive comfort and luxury by otherworldly beings at a tragic cost. The Japanese culture is a rare one in treating the supernatural with respect and that element, coupled with haunting imagery and a profound sense of the ethical, made this film stand out at the time and still today.

17. La Strada (1954)

Another of the great international film makers was Italy’s Frederico Fellini, who had the unique ability to mix fantastical imagery with believable everyday drama to deeply moving effect. Though he created far flashier and more commented upon films (not always the best comments, though), his enduring masterpiece may well be this deceptively simple story of the effects of both kindness and cruelty on human beings.

Brutish Zampano (distinguished Mexican-American actor Anthony Quinn) makes his living travelling from place to place with a rather tacky strong man act. Needing an assistant he, in effect, buys sweetly simple-minded Glesomina (Giulietta Masina, the director’s wife and perhaps the greatest tragic-comic actress in film history) from her destitute family. He treats her terribly (and may have caused her older sister’s death under similar circumstances) but she has a love for him anyway.

However, a catalyst in the form of a philosophical clown named Il Matto or “the fool” (Hollywood actor Richard Basehart in a superb performance) brings things to a tragic head due to his kindness towards Glesomina and taunting of Zampano. Fellini’s images and pacing are first rate and the principle cast members never gave better performances again in one of the most touching films of all time.

18. Diabolique (1954)

For those interested in labels, director-writer Henri-Georges Clouzot is often tabbed as the “Alfred Hitchcock of France”. This maker of dark thrillers, sadly limited by his delicate health, didn’t have the commercial slickness or extended cannon of his more famous counterpart, but his best films have a bite rarely found in Hitchcock’s work.

In the decades since his death in the early 70s, a number of his films have been reexamined and elevated and now look somewhat better than his biggest international hit and the film which is still his best remembered. However Diabolique (more properly Les Diaboliques) is a still a great introduction piece.

Taken from a novel written by the team which eventually created the source material for Hitchcock’s much lauded 1958 Vertigo, Diabolique tells the sinister tale of a murder plan gone very wrong indeed. The very fragile Brazilian headmistress (Vera Clozot, the director’s wife, who suffered from even more delicate health than her husband) of a run-down, second rate French boarding school would love to be done with the place and return home but is tied financially to her hated, intractable husband (Paul Meurisse).

The teacher/former mistress (the great French actress Simone Signoret) he has also mistreated helps her hatch a plot to kill him and make it look like he drowned in the school’s scummy pool during the off season. The murder, done in sweaty detail, seems to go as planned but the body vanishes from the pool and evidence suggests the victim may not be so dead after all….

This is the type of film which loses something after the first viewing but that first time can be a fun roller coaster of a cinematic ride and great for the younger viewer.

19. Seven Samurai (1954)

Japanese culture can quite often be very alien to those outside of that culture. Perhaps the best entry point into the world of Japanese cinema is the oeuvre of one of the world’s finest film makers, Akira Kurosawa, who is also considered the most western of great Japanese film makers as well (a fact which often did not sit well with those in his own country).

He is often favorably compared to the great Hollywood film director John Ford in terms of excellence across a variety of genres over several decades. He could create deeply incisive dramas, humane comedies and thrilling, and surprisingly deep, adventures films. His cannon is full of masterful works but perhaps the most famous (and somewhere near the his finest) is this mammoth (four swiftly moving hours!) film.

The story, as is often the case, is deceptively simple. A small rural village is being ruthlessly plundered on a regular basis by a horde of bandits. To put an end to this they enlist the aid of a number of warriors/samurais-for-hire, each of who have a story and issues of his own (the most prominent played by the great Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune, a Kurosawa regular).

The battle scenes are still among the best ever staged on film and the insights into character and settings are a sign of how a master film maker can turn even a genre piece into a deeply felt work of art. (Contrast this film with the Hollywood remake of 1960, The Magnificent Seven, this film’s original title. That is a good action film but only that and shows how much more this one has to offer.)

20. Lola Montes (1955)

Quite often younger generations love to think that they have made a rediscovery/reclamation of something which was unjustly condemned to the trash heap. One of the great cinematic refurbishments will always be Austrian born director Max Ophuls’ Lola Montes.

Ophuls had been a rising cinematic star before having to flee his homeland during the Nazi era, enduring a trying spell in Hollywood (which looks way better to modern eyes), and found success again upon returning to Europe. Alas, his luck ran out again with this, his biggest gamble and, as it so happened, his last film.

This pseudo-biography of the infamous 19th century courtesan (played here by prominent pin-up style actress Martine Carroll, forced upon the director by the producers) was his first film in color and widescreen and, with its deliberately non-chronological continuity, proved to be confusing to its original public (including the critics) and flopped badly.

Even worse, it was later chopped to pieces in the futile hope reissues would recoup its cost. Though way too late to help Ophuls in life, the film has been rescued, restored and proclaimed as one of the greatest films ever in its use of color and anamorphic composition, with its time structure now looking quite modern.

21. Bob Le Flambeur (1956)

Another figure fated to be rediscovered by a new generation was France’s Jean-Pierre Melville. Melville, who lived to an age neither very young nor old, was a bit of an ill fit in cinema history. A heroic figure in the French resistance during World War II, he gained a foothold in the years just after that conflict but just before the Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) period and he was far more mature than most of the novice film makers/young man who started that movement.

However, his rather existential crime thrillers/character studies now look to be among the essential films of that period, far more in the present than at the time. Taking a cue from the gritty Hollywood gangster films so beloved by the French film makers/students of that period, Bob Le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler) focuses on Bob (Roger Duchesne), a Bogart-esque man of the criminal world, well into middle age, tired, having seen it all, but possessing a code of honor which separates him from the majority of the low souls surrounding him.

The plot involves a big heist, an eager young apprentice for Bob, and a lovely young woman loved by both men but who can only rightfully belong to the younger man, requiring a noble sacrifice. Anyone ever seeing a Bogart film knows the plot but Melville’s informal, realistic technique married to a deeper emotional resonance makes it all seem new, reinvented.

Though Melville would have less than twenty more years to make films and would not be prolific, he would surely make his mark with this and similar fine efforts.

22. The Burmese Harp (1956)

Another prominent Japanese film maker to bring through to international renown during the post World War II period was Kon Ichikawa. Though he had been a director for a decade at the time of its release, his lovely anti-war film The Burmese Harp was his big breakthrough.

Astoundingly based on a Japanese children’s novel, the film tells the tale of a musician attached to a military unit in the capacity of being a harp player to calm the stressed soldiers.

The story opens at the war’s end and all are hoping to live peacefully and put all fighting aside. Sad to say, the spirit of war isn’t so easily quelled and the peaceful soul at the center of the film decides that sacrifice to a greater purpose is far more beneficial. This is a most spiritual and uplifting film, which might come as an unexpected surprise to some, given World War II rhetoric. Many years later Ichikawa remade this Academy Award nominated effort in color but this first version was the truer effort.

23. The Apu Trilogy (1955-59)

India is often considered to be a third world country and, due to this perception (appropriate or not), its film industry is frequently overlooked. The irony in this is the fact that the populous sub-continent is a most fertile source of film making with a vital film industry and a robust film going audience.

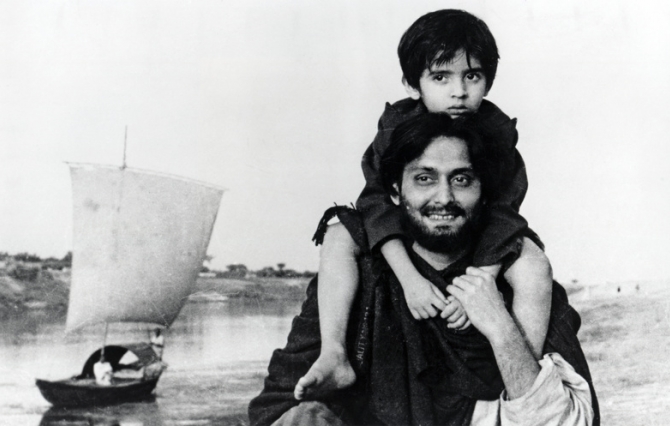

To further this irony, one of the world’s very finest film makers was a native Indian and worked in the Bengali cinema all of his stunning career. Satyajit Ray was interested in film from a young age and learned the business working with Jean Renoir, among others filming in his homeland, in an apprentice type of relationship.

While doing this, he raised his own budget to make Pather Panchali (1955), the first film in what would become as The Apu Trilogy. Based on what was already a classic Bengali novel, the film, and the two which would follow (Aparajito, 1957 and The World of Apu,1959) detail the life of its central character from boyhood in a small Indian village through his student days, happy marriage, and that marriage’s sad ending and aftermath.

With no money for sets, costumes or professional actors, Ray used the Neo-realist methods and found a great verisimilitude married to a profound understanding of theme and character (he had a miraculous touch with non-professional actors as well). Ray would win world renown for these films and go on to put himself and Indian cinema on the international map and many of his thirty plus films would be acclaimed as masterpieces, but to many none would be as memorable as his superb early triptych.