8. The Man Without a Past (2002)

Finland’s Aki Kaurismaki has been gathering a following, cult in some places, mainstream in others, since the 1980s. He had seen a lot of growth in the 90s but he came into his own even more in the new century. Perhaps his finest hour to date is The Man Without A Past.

As with most Kaurismaki films, the picture is a deadpan black comedy with quite serious underpinnings. A nameless man (Markku Peltola) arrives by train in Helsinki. In a park he is beaten senseless, literally, by criminals and has no memory of anything, including his identity. No one is in any hurry to help him so he takes to life on the streets and starts to re-build his life from scratch. The film has its moments of dark humor but the theme is serious.

If one was deprived of the patterns and influences which have governed their life, what new life would the individual create and would it be a copy of the lost old life? The result certainly impressed many and the director scored the Grand Prix at Cannes and an Oscar nomination for Foreign Film. Oddly enough, the film maker has slowed considerably since, though he is far from elderly. He has made only two other films to date, but is still much acclaimed and admired.

9. Talk to Her (2002)

After the triumph of 1999’s All About My Mother, many wondered if Pedro Almodovar had turned a corner into deeper and more profound works or if that film was a fluke. Happily, the answer was the former and the director had indeed found a way to blend his trademark outrageousness with more profound underpinnings. The beauty of it all is that no one in the film world can take such wild, mostly sexual, situations, which sound too extreme to be likely, and bring them to such meaningful life.

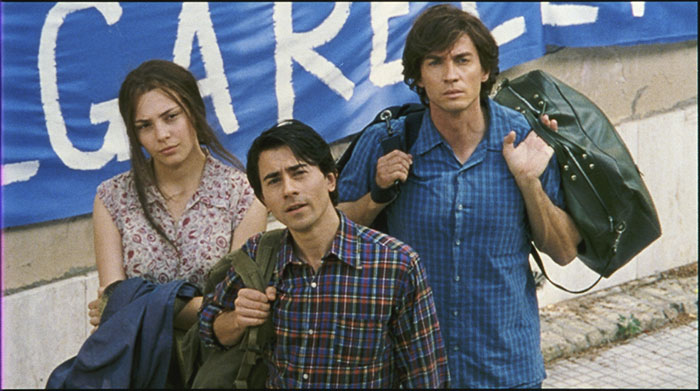

The director’s immediate follow-up to his 1999 film, Talk to Her, is a perfect example of this phenomenon. Benigno (Javier Camara), a journalist and Marco (Dario Grandinetti), a male nurse, meet by chance and strike up a friendship. By a wild coincidence, they have something most unusual in common. Benigno is in love with Lydia (Rosario Flores), a female matador and Marco loves Alicia (Leonor Watling), a young dance student.

The common thread is that both women are comatose and patients in the clinic where Marco works! A big difference is that Benigno actually had a relationship with Lydia before the accident which put her in a coma while Marco never knew Alicia when she was awake! As usual with Almodovar, the course of the story is a crazy and unexpected one but somehow the mood shifts into a dramatic and most touching mode.

As is often the case with the writer-director the story will end in both tragedy and unexpected triumph for various respective characters. Critics and fans alike raved over this one but the Spanish Film Academy rather churlishly (jealously?) refused to submit the film as Spain’s official entry for the Foreign Picture Academy Award. However, the writer’s branch ended up voting Almodovar his second Oscar. Happily, his work has been of a similar quality ever since.

10. Best of Youth (2003)

In the US in recent years television has begun to be looked on as a viable medium in which serious dramatic artist can tell stories which might have a hard time finding funding or a place in the cinematic marketplace due to length and/or subject matter. However, this trend has been going on in Europe for decades, especially for limited longer form stories of a more intimate and personal nature. One of the best of these is the Italian production Best of Youth.

The title is taken from a poem written by the great neo-classical film maker Pier Paolo Passolini (about whom the director of this film made a documentary). This is fitting since this seven hour film is a family saga in the style of a number of well regarded Italian films, notably Passolini’s classic Rocco and His Brothers. (It was originally shown in four parts on TV before playing in two three hour plus installments in theaters.) The story line covers the years between 1966 and the start of the 21st Century.

The family is a typical middle class family named Carati. The principal focus is on the two family sons, troubled Matteo (Alessio Boni), who rejects a medical career without having a plan B, and Nicola (Lugi Lo Cascio), who becomes a psychiatrist. In point of fact, mental issues will haunt the lives of the brothers and family, which are crystallized by their long relationship with Giorgia (Jasmine Trinca), a deeply troubled young woman who will suffer terribly due to her emotional issues.

The film plays out with great subtlety and detail and shows how family histories can sometimes take unexpected turns and the various members have to find a way to make peace with traumatic events. Past that, the film is a rich evocation of this vital period in Italian (and 20th Century) history.

Many consider this one of the great television productions of all time regardless of country. (In many quarters, it is also thought of as a theatrical production.) The director is Marco Tullio Giordana and the film won the Un Certain Regard award at Cannes. To date, he has yet to create another film as prominent and acclaimed (though his 2005 film Once You’re Born You Can No Longer Hide was entered in competition at Cannes also). However, he presented the cinematic world a masterpiece with this one.

11. Saraband (2003)

All things must pass. Ingmar Bergman had been a staple of the Swedish film world since the 1940s and an imposing presence on the world cinematic scene since the 50s. He stated his intention to close his distinguished directorial career with 1981’s much lauded Fanny and Alexander but he never really seemed to leave the motion picture world entirely.

While still directing for TV and his beloved stage, he also contributed screenplays for other directors. However, even the great are finite and, as the new century opened, Bergman must have sensed his own end was near. He decided to direct one more film, and one that summed up both his career and life. One of his most acclaimed and personal productions of the 1970s was the Swedish television mini-series Scenes From A Marriage (which was shown in an edited version in cinemas outside of Sweden).

Bergman was married often in his life but one of his most profound relationships was with one of his lead actresses, Liv Ullman. They cohabitated for years (many of them on a small and very private island which drove the humanitarian Miss Ullman a bit crazy due to useless isolation) and produced a daughter, Lin Ulmann, but never married.

Nevertheless, the series was built largely on the demise of their non-marriage but not, oddly enough, their relationship. The supreme proof of this is the existence of this film, which picks up the relationship of the main characters of Scenes an unspecified number of years after the end of the events in the original production.

Marianne (Miss Ullman) is feeling lonely, among many other feelings (and she always had many feelings). She decides to seek out her first husband, Johan (long time Bergman surrogate Erland Josephson). Both tried marriage a second time after they parted. Her subsequent husband disappeared and presumably died in a glider accident. He ended up divorced again after having a son by his second wife (and an abortion had started the original pair’s marriage down its bleak ending path).

Johan is happy to see her, especially since his son Hendrik (Borje Ahlstedt), an unbalanced n’er do well, is giving him a very hard time. The two, in the end, can give one another only so much comfort but they also understand that they know one another better than any other person knows either of them.

This is not unlike the relationship of the director and actress. Not everyone with their history could or would have gotten together for one last film to illuminate that relationship. Yet, it was really quite appropriate that two of the most introspective and revealing artists in cinematic history would have done just that. It might not have been as grand a finale as Fanny and Alexander was intended to be but it was quite fitting finale for one of the most personal film makers in history.

12. The Triplets of Belleville (2003)

Once animation was the kingdom of Disney and that studio’s films and those limited efforts of whatever other animated studios which came out from the 30s until late in the 20th Century. These films were mostly family fare and the beloved ones became “family classics”.

However, starting with the very adult work of American Ralph Bakshi and the magical works of Hayao Miazaki in Japan, animated gradually was perceived as an art form which could express and illustrate themes and concepts which wouldn’t quite work in a live action film.

One delightful and offbeat contribution from Europe was this unique French film, the debut of director and writer Sylvain Chomet. The director had created the notable short film The Old Lady and the Pigeons and had worked as a comic book artist. Perhaps this background explains why this film looks as a very stylized comic anime.

The story involves a plucky senior citizen, Madame Souza, who sets out to rescue the beloved orphaned grandson, Champion, whom she raised and who has been kidnapped by gangsters, who wish to throw the Tour-De-France, in which the young man is competing. Madame Souza and Champion’s rotund dog Bruno traces the criminals to the town of Belleville but find the job too big for them at that point. Enter the Triplets of Belleville, sisters who had been big singing stars in the 30s and who still have a trick or two up their sleeves.

The film is wonderfully surreal and richly drawn (actually a bit like a Betty Boop cartoon on steriods). Rated PG-13, this was not really a children’s film but it remains a delight for more open minded families. Animation takes a while to create, thus Chomet’s career has been a bit limited since, though his next feature, 2010’s The Illusionist, giving life to an unfilmed Jacques Tati screenplay, was much acclaimed. His future projects will be much anticipated.

13. Life is a Miracle (2004)

The superb Serbian director Emir Kusturica continued to create amazing films with this effort, coming on the heels of his triumphs Underground (1995) and Black Cat, White Cat (1998). Life is a Miracle, a title both ironic and sincere, tells a romantic story of the boy meets girl variety but tells it against the most unfunny backdrop of the Bosnian-Serbian conflict and heaps some tragic situations on its main character.

Railway engineer Luka (Slavko Stimac), who is Serbian, takes a job running a new railway station in a remote section of Bosnia. He is rather ridiculously optimistic about such things as his mentally unstable wife,Jadranka (Vesna Trivalic) and the fact that war is coming quickly to even his isolated part of the world.

Cruel events separate him from wife and grown son Milos (Vuk Kostic) and in most films bringing them back would become the focal point. However, circumstances throw Luka with a lovely Muslim Bosnian prisoner named Sabaha (Natasa Solak), with whom he finds unexpected love. Their path is far from obstacle free (and way more dramatic than a romantic comedy would ever have it).

The section of the world which produced the director has not had a happy history…well, since ever, but the 20th and 21st Centuries have been quite troublesome, to say the least. To be able to make honest films about that history without them coming across as grim, much less being able to find a comic side to it all is remarkable. Kusturica always concentrates on plucky survivors who surmount hyper surreal situations. Life is a Miracle is a fine addition to this line.

14. The Sea Inside (2004)

The newly reinvigorated Spain continued to be a source of fresh, excellent films with the arrival of the 21st Century. One surprise is that so many of its best artists found international careers, including success in Hollywood.

Actor Javier Bardem was able to move seamlessly from Europe to the US in his work and director Alejandro Amenebar hit pay dirt with the fine, subtle horror film The Others in 2001. This set the stage for the two men to join together to create what is one of the finest films on either man’s resume.

The Sea Inside is the story of Ramon Sampedro (Bardem), who was left a quadriplegic after a driving accident and then fought a 28 year long legal battle to be allowed to die with dignity. His battle was punctuated by two women, Julia (Belen Rueda), a lawyer with physical challenges of her own and who wishes to aid him in his struggle, and Rosa (Lola Duenas) a simple local women who befriends him and tries to convince him that life, even in the condition in which he exists, is worth preserving.

This could easily have been one of those inspiring dramas about overcoming physical challenges but, instead, it’s a thoughtful meditation on what constitutes quality of life and what right the individual may have over his own existence.

Though Bardem was not nominated for this performance (and he is no stranger to the Academy, being an Oscar winner) it is still one of his best. This may well be Amenabar’s best work to date and the Academy saw fit to reward it with the Best Foreign film Oscar. This success has allowed both artists to keep enjoying fruitful international careers.

15. Downfall (2004)

After reunification, Germany seemed to finally be largely healing from the traumas of its divided post-World War II existence (and the western side had accomplished what has long been dubbed an economic miracle in the years just after the war). One bit of evidence to support this is the existence of this film.

A number of productions over the years have told the story of the highly dramatic events of the ten days in German dictator Adolf Hitler’s bunker before the impending fall of Berlin to the Allied forces caused him to take his own life (and causing several of the faithful around him to do likewise).

The major point about this film is that it was a German production as opposed to all others, which were made by foreign companies, and it starred a distinguished German actor as Hitler (other Hitlers had included Alec Guinness and Anthony Hopkins). That the Hitler of this film was the great Bruno Ganz, the kindly screen presence with the tender eyes, best remembered for playing an angel in Wings of Desire (1987), pointed up what else made this film different.

Yes, director Oliver Hirschbiegel (who has not done much since) and writer Bernd Eichinger used many fine historical texts to create this film, as had the others, but they had something the others did not. In her later years, Traudl Junge, who, as a young woman had been Hitler’s secretary in the last years of the war, broke her long silence and not only wrote her memoirs but appeared on screen as the subject of the excellent 2002 biography Blind Spot (which is excerpted as a prolog in this film).

Her portrait of Hitler was of a man who was quite kind to her, but evil in so very many profound ways. She admitted she was taken in, though she should have known better. Her story helps to frame this richly detailed film which shows those ten days from a number of perspectives.

The linchpin is Ganz, though. His Hitler is surely a monster but a human one who did the things he did due to issues of his own. The very fact of the subject and the treatment meant that the reception would be divided, though even those who objected to the humanization admitted that the film was a superior and well research production and it was rewarded with an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Film.