13. Les Diaboliques (1955)

Life, much less the film world, is rife with ironies. H.G Clouzot was and is known as “the French Hitchcock” largely on the basis of his biggest international hit, Les Diaboliques (The Friends or The Devils, depending on translation).

One irony is that the authentic Hitchcock just missed buying the rights to the French novel which became the basis for this film. The next irony is that he snapped up the writing team’s next effort, a novel which became his 1958 film Vertigo.

The third irony is that the pseudo-Hitchcock’s effort was a great hit while the real thing’s film was a relative flop at the time. The fourth irony is that time has sharply reversed that judgment and Vertigo is considered a great work of cinematic art while Les Diaboliques is now looked upon as a skillful confidence trick.

Both films concern haunting crimes in which passion and violence intersect and the events are overshadowed by the specter of resurrection. Les Diaboliques is set in a seedy boarding school in rural France.

It is ruled over by a sadistic headmaster (Paul Meurisse) who sadistically dominates his delicate South American wife (Vera Clouzot, the director’s equally delicate and ill-fated wife) and sturdier, but brutalized, mistress (the great French actress Simone Signoret), a teacher at the school.

It seems husband and wife would dearly loves to be shed of one another but neither can buy the other out. The desperate woman, who suffers from a pronounced heart condition, succumbs to an idea advanced by the mistress, now supposedly an ally: they will murder the husband and make it look like he drowns in the school’s decrepit pool (the story takes place in off season).

During a school holiday they lure the man to an isolated locale and commit the crime to sweaty and nerve wracking effect and dump the body…only to have it never surface without any trace to be found when the pool is drained. Even worse, evidence starts to mount that the victim may not be quite as dead as thought…

.Clouzot’s set pieces are brilliant (and no one seeing the film ever forgets the last half hour) and Mrs. Clouzot, who had a truncated career to say the least (she died less than five years after making the film), gives an unforgettable performance. (The expert Signoret is fine as well, but she feared the wife-husband duo would hijack the film from her and she was largely right.) The difference in this film and Vertigo is that both plots have a surprise twist (and Les Diaboliques twist looks a bit less twisted with the years).

While Clouzot holds it until the end, Hitchcock made the controversial choice to reveal the twist two-thirds of the way through his film and concentrated on the psychological underpinnings of the true relationships for the remainder of the film.

Frankly, though these choices caused one film to be thought of as more satisfying than the other at the time, it’s far easier to discern the more profound work now. However, this film opened the door to the reevaluation of Clouzot’s earlier and better works, an irony in and of itself.

14. The Ladykillers (1955)

All things must pass and in the cinematic world, based on commerce and fickle and changing public tastes as much as art, things tend to pass even more quickly than in other spheres.

A case in point is Ealing Studios. Started in the 1930s as “quota-quickie” studio (making films purely to satisfy the quota of British films mandated by law in order to import Hollywood films) the company limped along with a few popular comic stars until the war years and the superior new management of Michael Balcon (later a Sir and even later grandfather of the great actor Daniel Day-Lewis) began to raise their profile.

However the truly great years started after the war, especially with the introduction of a wave of wry, comically reserved, civilized (but far from uppity) comedies which celebrated average British life and its many aspects of regional color (or colour).

A typical Ealing film (and the name comes from a London neighborhood) features a communal group facing some great challenge which they struggle in a cheerfully stiff upper lip way to overcome (and, so typical, there are rarely any true villains in the films). Ealing did not like stars, though it favored character actors, and loved writers and directors.

Oddly, they produced no major directors (doing a bit better with writers) and inadvertently created one of the least likely stars of all time, the superb but theatrical, introverted, and highly subtle Alec Guinness (who admitted that he didn’t particularly like making the five films he worked on at the studio, one of the hubs of his film career).

The comic line started in earnest with 1947’s Hue and Cry and started to slow as TV came to England and began to leave no place for the small scale, non-starry films of the kind which Ealing specialized in making. They left the stage in a classy way when the BBC, Britian’s great radio network, bought the studio to house their budding television network.

Before the movies turned to TV shows, though, there was one last masterpiece, and a rather atypical Ealing effort, like most of Guinsess’ films there (and a rare color effort for the studio).

This film is The Ladykillers, directed by one of Ealing’s great discoveries, Alexander “Sandy” McKendrick (who had a striking career consisting of only six films!) from a spectacular script by William Rose (an Academy Award nominee).

The plot, set in a quaintly rundown section of London, significantly near a railroad track, centers on Mrs Wilburforce (77 year old Katie Johnson in the only great role of her career, and the last), a sweetly foggy but most proper relic of the Victorian era. She rents rooms in her charmingly crooked little house and who should come to rent but a real crook, one Professor Marcus (a rarely over-the-top Guinness, channeling another Ealing great, Alistair Sim).

The “professor”, who claims to need space to rehearse with his classical group (consisting of British comedy stalwarts Cecil Parker, Danny Green, Jack Warner, and Herbert Lom and a young Peter Sellers, long before their pairing in the Pink Panther films). Actually they are robbers and Mrs.Wilburforce’s house is in close proximity to their target.

The old dear stumbles upon their plot and she’s as doomed as doomed can be…or is she? (An odd point in McKendrick films is the triumph of innocents to a lethal degree in dangerous situations.) The public and critics loved it then and now and it provided a most happy finale to Miss Johnson’s career and life (including a British Academy Award) and for Ealing itself.

15. Ordet (1955)

Joining Robert Bresson in the pantheon of great “personal” film makers is Denmark’s Carl Theodore Dryer. Eternally known for the silent classic The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), this great spiritual/philosophical film maker was fairly prolific in the silent era but funding became harder to come by as the years went by (especially after the acclaimed but costly flops of Joan and 1932’s Vampyr) and, thus, he ended up averaging only about a film a decade for the last half of his career.

The entry for the 50s was Ordet (The Word) but it proved one of his best and a very rare money maker! Taken from a well known Danish play, the plot revolves around two feuding farm families, both governed by ultra-pious patriarchs, only pious in decidedly different ways.

The crux of the argument comes when the son of one family wishes to marry the daughter of the other. The girl’s father, a sectarian leader, objects to the boy’s religiously troubled family, consisting of a faithless oldest brother with a pious wife having a troubled pregnancy, and middle brother who has lost his mind due to his studies as a philosophy student and now believes himself to be Jesus Christ! He also freely condemns all others for the shallowness and falsity of their faith.

This thorny situation comes to a head with a tragic turn of events followed by what can only be termed a miracle (and one of the few convincing scenes of such a nature in film history).

Filmed in Dryer’s famed long, knowingly static shots with an emphasis on the faces of the participants, the film has a rare honestly truthful and deeply felt resonance which could only have come from someone who truly believes in the values his film is expressing. Dryer’s path was a lonely and rocky one but his legacy is truly transcendent (though he would only get to make one more film after this masterpiece.

16. Rififi (1955)

Some films are so seminal that they become virtual sub-genres unto themselves. One such film was John Huston’s 1950 crime thriller The Asphalt Jungle. This film examining the events leading up to and following an intricately planned heist, told largely from the criminal’s point of view, was so solid and influential that many of the films it inspired were also excellent and big hits.

One of the best was a French entry with surprising roots in Hollywood. Jules Dassin may sound like a European name but he was, in fact, from Brooklyn and had been establishing a very good career in Hollywood creating what are now recognized as superior film noirs (Brute Force 1947, The Naked City 1948) before running afoul of HCUA and ending up blacklisted.

He fled to Europe and directed Night and the City (1950) in England before the tentacles of the blacklist caught up him and caused him not to work in the film industry for some five years. He was able to get back into the film world when he sold the script he had adapted for a French crime novel which became the crime classic Rififi. He also managed to have himself cast in one of the lead roles, albeit using the stage name Perlo Vita.

At the last minute the sympathetic director already chosen, Jean-Pierre Melville (a future director of great crime films at that moment in time) stepped aside and gave Dassin his chance to fully come back to film making.

Like The Asphalt Jungle, the film concentrates on a number of criminal types, some with decent qualities, who are in desperate straits which money can help, causing them to participate in a daring caper.

The plot comes off but they have not reckoned on the consequences, especially since they cannot remotely trust one another. The difference Dassin brought to the table was a keen eye for the Gallic crime milieu and the stunning robbery sequence. This set piece runs for approximately half an hour with no dialogue, no music, and few sound effects.

As the viewer watches, the men tortuously carry out the crime and, though one can’t admire their crooked intent, their skillful and hard work is to be considered (surely real legitimate work couldn’t be so difficult).

The tense and unusual finale is also notable. This was not a big budget effort (which is perfect for the plot’s seedy context) and it was able to fly under the radar sneak its way into being a big hit with audiences and critics, even in the US.

Dassin would go back to work, though it wouldn’t be truly regular until after his big 1960 hit Never on Sunday. However, he would never truly return to work in Hollywood. (The basic formula of this film would also yield The Killing, the following year, the first notable film from Stanley Kubrick.)

17. And God Created Woman (1956)

Even the art house crowd needs some carnal pleasure and, though many would showcase adult sights and themes, no one provided this quotient more enthusiastically than Russian extracted, French film maker Roger Vadim.

Calling Vadim artistic may well be pushing it a bit, though he did design his films artistically and often chose distinguished continental players to fill out his casts. However, the raison d’être of his films was a succession of nubile blonde actresses. One thing even his most virulent detractors would give Vadim was his superb tastes in women.

Though there were many protégées he was famous for showcasing wives/partners Catherine Deneuve and Jane Fonda (yes, they could act, but who knew it until they broke from Vadim). However, the purest, most famous, most…well, Vadimist of them all was his first wife and protégée Bridgette Bardot.

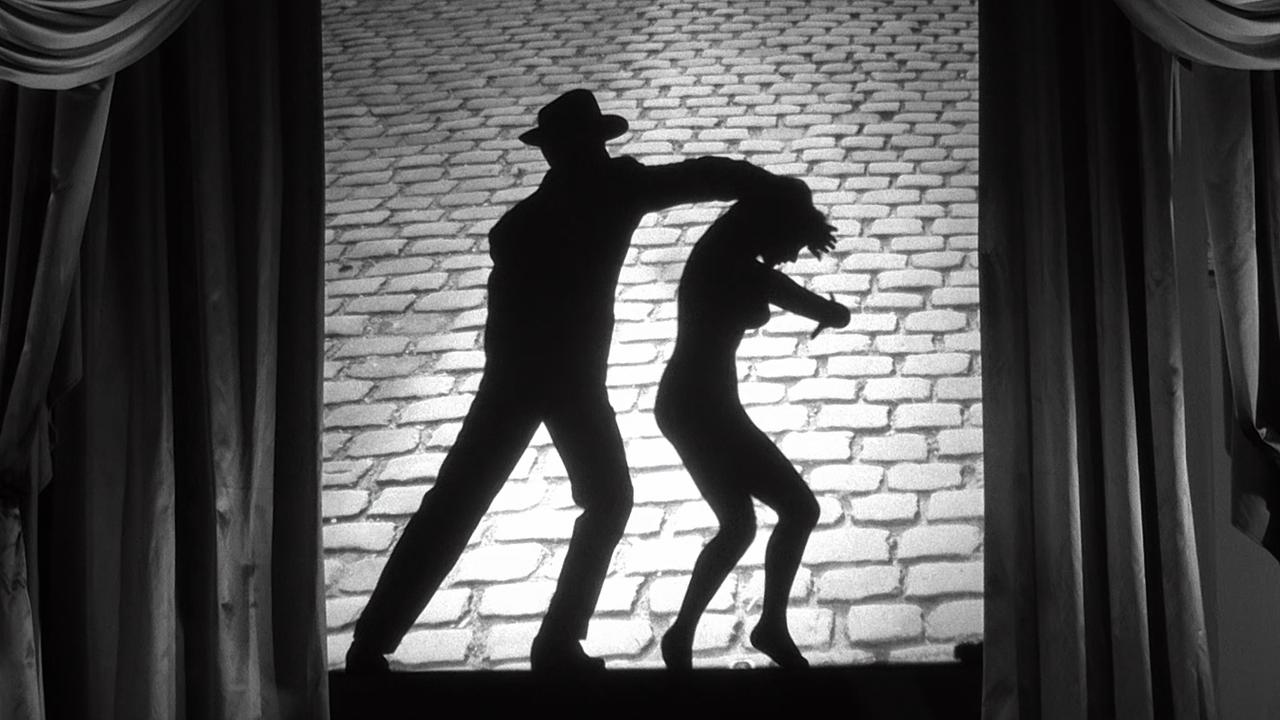

If ever the term “sex kitten” had any meaning then that appellation found its perfect recipient in Bardot. Lovely and sensual and very sexual in a very natural and pre-conscious way, Bardot was the original wild child both on and off screen and seemed to be perfectly oblivious to the effect she had on others. This premiere showcase for both her and Vadim is wonderfully composed in deluxe color and cinemascope in a way which makes sense of the 50s term ‘va-va-va-voom”.

The plot? Well, yes, there is one, something about an over-sexy and pre-knowing waif who marries into a family of men and proceeds to turn the household and surrounding town upside down.

Truthfully, it’s all an excuse for the star to Bardot it up in various states of undress showing off her sex appeal. The cast includes such fine actors as Curd Jurgens and Jean-Louis Trintignant (who had so much bigger and better before him). It didn’t matter, for Bardot wiped them all off the screen. However, she knew where her talent lay and turned to animal causes as she grew older and walked away from motion pictures rather than change (and, honestly, the world didn’t need an aging Bardot on screen).

As for Vadim, he never gave up his soft-core ways and did stir up it a bit from time to time but never again hit the bulls-eye quite the way he did here (and poor Fonda has been living with the legacy of their ultra-camp sci-fi romp Barbarella since 1967). This one is a guilty pleasure which is both a pleasure, though really the viewer, and makers, should feel guilty.

18. Bob Le Flambeur (1956)

Jean-Pierre Melville didn’t have to wait long for his good turn on Rififi to come back to him. He was a fascinating figure in film history. Melville was a dedicated member of the French Resistance during World War II and, after the war, edged into theater and film. He made a critical splash with the superb war based character drama Le Silence de la Mer in 1945 and then received a major boost when Jean Cocteau chose him to direct his screenplay for 1947’s Les Enfants Terribles.

However, his real métier would be found in crime based character dramas. One of his very best was his first, Bob Le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler). The title character (played by Roger Duchesne) is a gambler with a pronounced sense of honor…on his own terms. Bad luck at the gambling tables and other places caused him to drift into crime and he has a police record to prove it.

As the film opens, another bad streak is leading him into another ill considered crime venture. Complicating matters is his growing love for Anne (Isabelle Corey), a waif he has rescued from the streets and who appears to be mutually falling for Bob’s young partner in crime Paolo (Daniel Cauchy).

This one is truly a French film noir. Melville always created an austere atmosphere for his crime films and his many professional criminal protagonists, such as Bob, always have their own strict code of conduct, which sometimes they alone understand.

Obviously, he learned much from American film noir but he put his own spin on things and his genre films are among the best of their kind. He also pioneered the kind of editing and camera work soon to be enshrined by the French New Wave.

Sadly, there would only be nine more films in his filmography before his premature death in 1973. Though the critics were kind enough in his own time, his greatest regard would only come after death. In 2002 the acclaimed Irish director Neil Jordan remade the film as The Good Thief with Nick Nolte in the lead. It wasn’t a bad film but it showed how skillful were Melville and the original had always been.