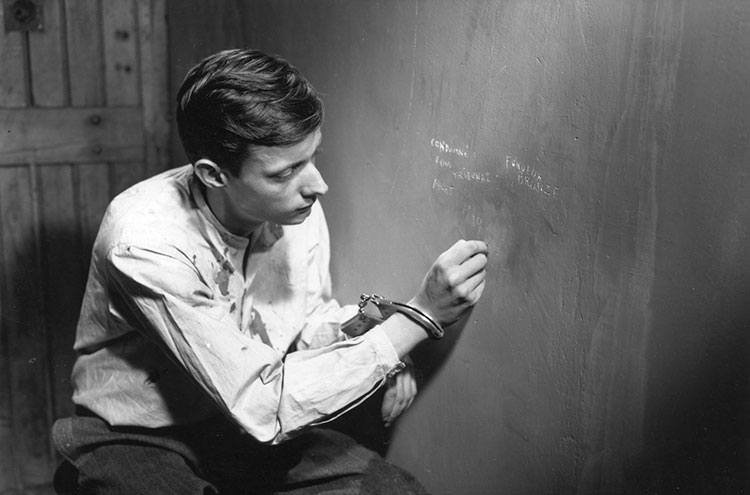

19. A Man Escaped (1956)

The 1950s were truly Robert Bresson’s decade. He was able to fund his films more easily during that decade then he ever would again and created films considered among his very best. Perhaps his greatest moment at the time was A Man Escaped, a film much admired in his native France (and other places and still highly held).

As ever with Bresson, the plot is single minded and quite austere in the telling. The film centers on Fontaine (François Leterrier, one of Bresson’s non-professional models), a prisoner of war, held by the Nazis during World War II. Simply put, Fontaine is determined to escape to freedom. His efforts are not tolerated by his captors, who warn him that the eventual cost could be death.

The film focuses on Fontaine’s meticulously planned efforts at escape. There are no real subplots, no comedy relief, no hint of romance, nothing to distract from the matter at hand. As ever with Bresson, staying resolutely on the outside leads to a profound understanding of the interior.

There is a strangely ascetic and spiritual quality to Fontaine’s quest for freedom. Bresson’s characters often achieve a unique transcendence in the spiritual journeys they undertake.

The viewer can feel, without being told, that Fontaine will know himself and his own power far greater from this time than he ever would have otherwise.

It’s not a surprise that the French, many of whom had endured similar experiences a short time later, would love this film. However, it would help set the stage for another film of similar quality dealing with a far different journey. More of that later.

20. The Red Balloon (1956)

In the classic age of Hollywood (and British cinema) short subjects were often thought of as just filler to round out the features making up a typical movie going program. In Europe it was another matter.

Films were considered on the basis of skill and artistic quality regardless of length. Supreme proof of this is the reception of French film maker Albert Lamorisse’s The Red Balloon.

Lamorisse had scored a hit three years earlier with the stunning equine-themed short White Mane (to some, still his masterpiece), in thrillingly abstract black and white. The Red Balloon, made in color on the streets of Paris, is a film for which the word charming may have been invented.

A little boy (Pascal Lamorisse,the director’s son) finds the titular object and, like most children with a balloon, is quite enamored of it. However, the balloon has a mind of its own and it follows him everywhere and, this being a fable, causes way more havoc than one might expect a balloon to be able to generate.

The balloon makes enemies both for itself and its young master. However, fable conditions striking again, all the balloons of Paris come to the rescue. This wordless film has the perfection which can only be achieved in the shorter form. There is not a wasted or superfluous moment.

It also is a major plus that this film beautifully captures the endearingly run-down Belleville neighborhood of Paris (since demolished). Almost as unbelievable as the goings on in the film is the fact that it went on to win both the Palm D’Or at Cannes and an Oscar for its script!

This promised a great career for Lamorisse but luck was not with him. He made a few feature films, mostly well received in Europe but not well known in other parts of the world before his death in an aircraft crash in 1970.

21. The Seventh Seal (1957)

Sweden’s Ingmar Bergman had been a screenwriter in his native land since 1944 and a director since 1946, to much acclaim from the start. He had also scored something of an international hit with the delightful 1955 comedy of manners Smiles of a Summer Night (and comedy was rather atypical of the somber Bergman). However, his career might well have begun with The Seventh Seal.

The plot, taken from a play Bergman had written some time earlier, concerns a disillusioned knight (Max von Sydow) and his unbelieving squire (Gunnar Bjornstrand) returning wearily from the crusades after many years.

While resting on the Swedish coastline one morning, the knight is approached by a figure cloaked from head to toe in black, revealing only a chalk white face. The forbidding stranger announces that he is none other than Death (Bengt Ekerot) and he has come for the knight.

The man is not afraid but does have things he feels he must do (such as reaching his wife and home) and successfully challenges Death to a game of chess to be played out over a period, with the knight’s life as prize. As he and Death fence with each other, the knight and squire travel the countryside towards home.

Along the way they find a cross-section of disparate characters representing various aspects of human suffering and faith. Chief among those met are a husband and wife team of travelling players, holy fool Jof (Nils Poppe), who sees religious visions, and his solidly loyal and loving wife Mia (Bibi Andersson), who, along with their infant son, provide a more joyously positive view of life.

To say that this film had a lofty reputation for many years would be a great understatement. Though many critics and discerning viewers virtually genuflected at the mention of this film, Bergman felt it uneven and a more sanguine modern view tends to support that view.

The performances are excellent (von Sydow, Bjornstrand, and Andersson became Bergman staples and built mighty reputations due to their associations with the director). The cinematography is also quite stunning, making the film look like medieval religious paintings come to life and the film is rife with images which became staples of film education ever after.

The script and direction also provide many strong moments. However, looking at the film now, it’s obvious that the budget wasn’t too high and the film is rather plainly made as a result.

Also, the spiritual themes seem a bit overstated now (and many over the years have found the film ripe for satire). However, the fact that it took so many years for these doses of reality to hit many illustrates the greatness of its best parts.

22. The Cranes are Flying (1957)

Soviet cinema often seems to exist in a sphere of its own as so much of it concentrates on propaganda and concerns of the state, often with little regard for individuals. There have been notable exceptions and one of the most stylish and emotionally touching is The Cranes are Flying.

The theme of the film is the devastating emotional and personal effect of World War II on the morale and emotional life of Soviet citizens. The big difference between this film and many Soviet productions is that the larger theme is captured through the experiences of a representative character.

Veronika (Tatyana Samojlova, perhaps the one Russian actress to be a challenge to the divas Hollywood and a niece of the great acting teacher Konstantin Stanislavsky) is a young girl in love with Boris (Aleksey Batalov), the son of a doctor. Boris dies early in the war but his death goes officially unreported and Veronika won’t give up hope.

After her parents die in a bombing raid, Boris’ family asks her to live with them, only for her to fall victim to Boris’ unscrupulous cousin Mark (Aleksandr Shvorin), who rapes her and shames her into marriage.

The film then follows Veronika’s travails as she copes with both personal unhappiness and the larger trauma of a nation engaged in a life or death conflict. The director is Mikhail Kalatozov, who was a superb visual stylist and who seemed set for a great career, only created three more films before his abrupt death in 1973.

The others, including the stunning I Am Cuba (1964) were all fine work but none of them had quite the emotional weight of this film. Sadly, the leading lady’s career would also be blighted by politics (Hollywood knocked but Moscow said no and she was later forbidden to act), though she made a comeback before her death in 2014.

Though their careers on the whole may have been truncated, the director and star had this one shining moment on the international scene (and this was the first Soviet film to win the Palm D’Or).

23. Wild Strawberries (1957)

One hit can put a career on the map but a follow-up second can be the real making of a career. Ingmar Bergman, as previously stated, was no novice when The Seventh Seal broke big and he already had another major work in the offing while he might have been basking in the glow from the earlier film. The subsequent film, Wild Strawberries, was much more in keeping with what would become known as Bergman’s style than its predecessor.

The plot concerns an elderly and distinguish professor (Victor Sjostrom) who is travelling to Stockholm from his home in the country in order to accept a major honor. However, his sleep has been plagued by disturbing dreams which seem to portend his death.

During the journey, eventful but far from portentous, the old man recalls various key episodes in his life, in no small part thanks to a young hitchhiker (Bibi Andersson), who bears the same name and a striking resemblance to a distant cousin the man unsuccessfully loved in his youth (needless to say, Andersson is the cousin as well).

The result is an incisive and skillful account of the spiritual and emotional aspects of a life, something which would preoccupy Bergman for his entire career (one big difference being that the subject here is a male character).

The professor’s surreal dream and the skillful use of flashbacks, and how they are achieved, thanks in no small part to the cinematography of Gunnar Fisher, mark this as one of the great films.

A key ingridient of the greatness is the work of the cast. Andersson and Gunner Bjornstrand, who plays the professor’s son, were already becoming fixtures in the Bergman universe. Added to this is the magnificent Ingrid Thulin as the son’s stoically angry wife. However, the centerpiece is Sjostrom, in his only Bergman film.

In addition to acting, Sjostrom had been one of the bright lights of the first “golden age” of Swedish cinema during the silent era (Bergman alone created the second “golden age”).

After scoring with such memorable films as The Outlaw and his Wife (1919) and Korkarlen (1920), noted for their naturalism, he went to Hollywood as Victor Seastrom and created masterpieces such as The Scarlet Letter (1926) and his greatest film, The Wind (1928), but the public didn’t bite and, between that and the coming of sound, his directorial career faltered.

Wild Strawberries was his last film of any kind and a superb note on which to end. Whether Bergman meant it or not, the film was also a symbolic passing of the torch from one generational great to another.

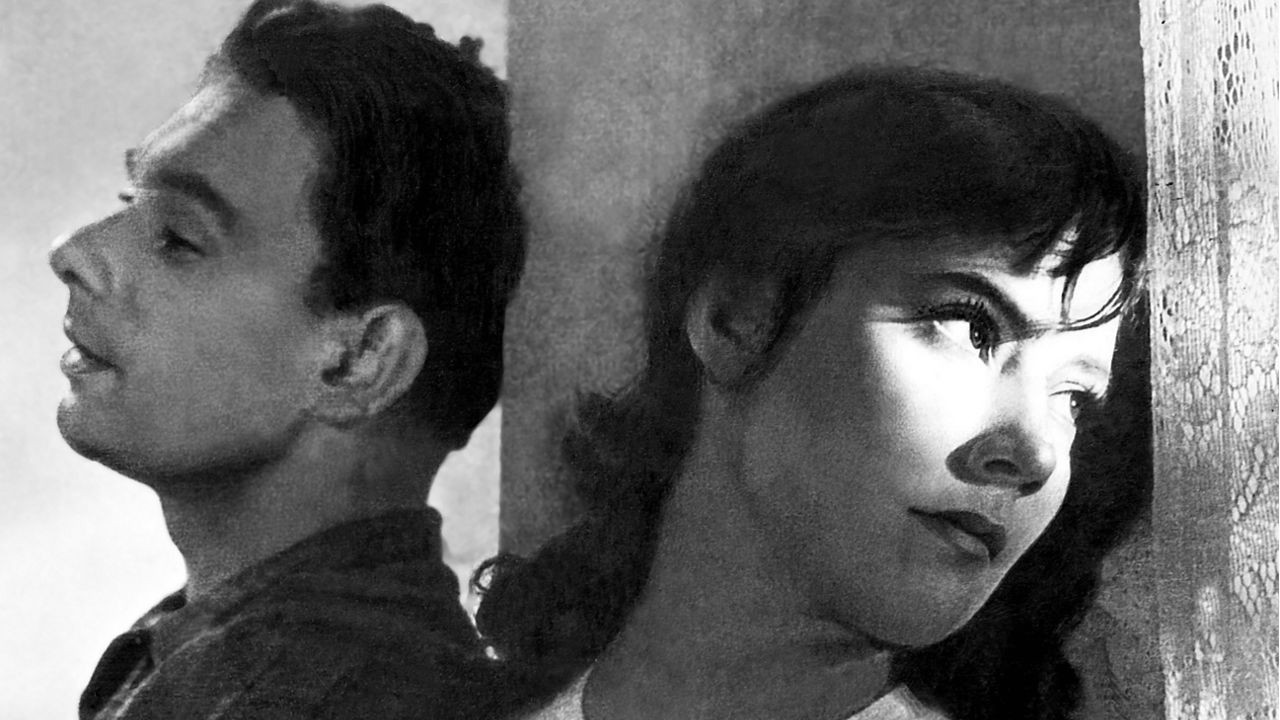

24. Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

Poland’s Andre Wadja surely deserves an award of some kind for longevity among notable directors, especially European ones (and did get one in the form of a lifetime special Oscar).

The films which really put him on the map were the three films which made up his “wartime trilogy”, A Generation (1954), Kanal (1956), and Ashes and Diamonds, the masterpiece of the set to the minds of several.

The plot, adapted from a novel well known in Poland, takes place on the day World War II ends. However, the end of the war is no cause for unbridled joy, at least in a quite battered Poland. The Nazis had performed quite a harsh number on the land and their defeat only serves to give rise to a new conqueror, the socialistic U.S.S.R.

In this confused atmosphere, it is small wonder that chaos is erupting. Two dedicated freedom fighters, (Zbigniew Cybulski and Adam Powlikowski) are assigned to kill the new communist commandant of their small, unnamed town. They had unsuccessfully tried before and now are in great danger.

During one tense night much will transpire but the results won’t be happy. This was surely a brave film to make given that the plot was so critical of those then in power. Wadja was always hard hitting and uncompromising and this well shot film is no exception.

The special ingredient, though, was Cybulski. He is often called “the Polish James Dean” due to the urgent immediacy and cuttingly rebellious presence he shared with his Hollywood counterpart. Sadly, thanks to a train accident a few years after Ashes and Diamonds, Cybulski would also share an early demise much like the fate of Dean.