25. Le Beau Serge (1958)

Unless one is speaking of a specific technical innovation, it is dangerous to call anything the “first” in the cinematic world, especially if the “first” is an artistic concern. One of the most memorable of film movements is France’s Nouvelle Vauge (or New Wave), a style which moved away from the ornate but rigidly stylish style of classic French cinema.

New Wave films were often shot with handheld camera, indulged in such innovations as the “jump cut” in place of formal editing, and displayed an interest in grittier and more proletariat concerns than that of traditional French cinema.

This became the French style of the late 50s and 60s and many historians state that the film which finally brought all the elements together and set things on their way was Le Beau Serge, the debut of the redoubtable Claude Chabrol, a true survivor in his own right with a lengthy career.

The film, as with many new wave pictures, is more concerned with character and interaction than plot. Francois (Jean-Claude Brialy), who has made a success after leaving his small provincial town, has returned for health reasons. He crosses paths with Serge (Gerard Blain), once a golden boy, now somewhat tarnished.

Francois had once idolized the dynamic, popular, attractive Serge. However, Serge was having his best days then and since that time has done little with his life and is trapped in a marriage entered into thanks to an unplanned pregnancy (which ended in a stillbirth). Francois hopes to somehow help Serge (though both have involvement with the same woman, complicating matters).

The first of anything big is rarely the best and, if Le Beau Serge is the first New Wave film, it also isn’t the best. It isn’t dynamic and innovative in the ways of the most memorable films of the movement, but it must have been a breath of fresh air in the oppressive atmosphere of the time.

It is, however, a well made study of two interesting characters and there is a new feeling present in the picture. It is also true that sometimes first films look primitive and crude. Though this film doesn’t reach the heights of other New Wave films, it isn’t a disgrace by any means. It is, in many ways, a true harbinger of better to come.

26. Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

It didn’t take the New Wave long at all to really find its footing and one of the first excitingly memorable films from that movement came from another critic turned director, like Charbrol. This director was Louis Malle and, though a somewhat early death curtailed his career in 1995, what he left behind on film was fine indeed and marked him as one of the best film makers to come from the New Wave.

His debut, Elevator to the Gallows, tells a tale somewhat familiar to film noir fans. An illicit couple (Jeanne Moreau and Maurice Ronet) have decided to kill the woman’s wealthy husband for a number of reasons. The man has worked out a masterful plot and the killing comes off without a hitch.

Too bad an electrical blackout has trapped him in an elevator, cutting off his planned escape. The woman frantically tries to think of a way to salvage the situation while other forces combine to tighten the noose around the pair even more firmly.

The story was a good one but the beauty was in the telling for Malle didn’t fall back on noir tropes but, instead, embraced the new and naturalistic feel of the period (one striking element is that the partners in crime are never shown on screen together).

A major plus was the casting of the actress who may well be considered the figurehead of the New Wave, Moreau. This was far from her first film and she was already a star with France’s legendary Comedie-Francaise, but she had virtually been waiting for the New Wave to make her a star.

Sensual, but not strikingly beautiful, adept, but more instinctual than mainstream film actresses of her day, she was a modern in a sea of more traditional actresses.

It’s impossible to imagine the New Wave (or the history of France film) without her. Another much commented on and most perfect touch is the spare but highly effective jazz score by American artist Miles Davis (and the French have always adored US jazz). This, the exciting editing, the dynamic composition and the other performances make this one of the great debuts in film history.

27. Mon Oncle (1958)

Decidedly not of the New Wave, but acclaimed to such a degree as to inspire national pride, Jacques Tati directed only six films (one a TV production). His films each contained only about five to ten lines of dialogue (mostly incidental), making him arguably (with the notable exception of countryman Pierre Etaix a bit later in time) the last great silent comedy film maker.

Though his first two films, the charming Jour de Fete (1949) and the much loved Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953) were hits, somehow the stars truly moved into the right position (after a long period of trouble for Tati, including a car accident) with his first color production, Mon Oncle (My Uncle).

It should be noted that Tati was always more of a formalist comedy film maker than the type of director who allows for any type of improvisational comedy to come through. He controlled all aspects of his films (the reason, mainly, it took so many years to put them together).

Except for Jour de Fete, his films all centered on his signature character, M. Hulot. The tall, slender Hulot is a most formal, civilized and genteel character but also gangly, gawky, antiquated and somewhat out of touch with the larger world. His eternal conflict was in getting through life in a world which seemed to speak a similar but slightly different language from Hulot himself.

Tati would always frame the character’s comic adventures in a world which somewhat looks like the world as it is generally known but which is exaggerated to a greatly stylized degree. There was virtually no location shooting, just shots created on carefully designed sets (which worked well for this film but lead to major disaster for Tati later).

In this chapter of Hulot’s saga, he is living in a charmingly rundown old apartment building when his prosperous brother and sister-in-law decide that he must join the mainstream world and the right wife, one of their choosing, is what is called for to make it happen.

Only their precious young son really “gets” his uncle.The ultra-modern design of the brother’s home and office become jokes in and of themselves, along with running gags such as Tati’s endearing use of a pack of rather cute stray dogs.

This is all to the good as Tati was a rather cold and aloof figure (as is often pointed out by critics and historians) and his comedy is much more of a twee, amusing nature than laugh out loud funny. Still, this perfectly worked out artifact of a more conservative and standardized era is a lovely treat.

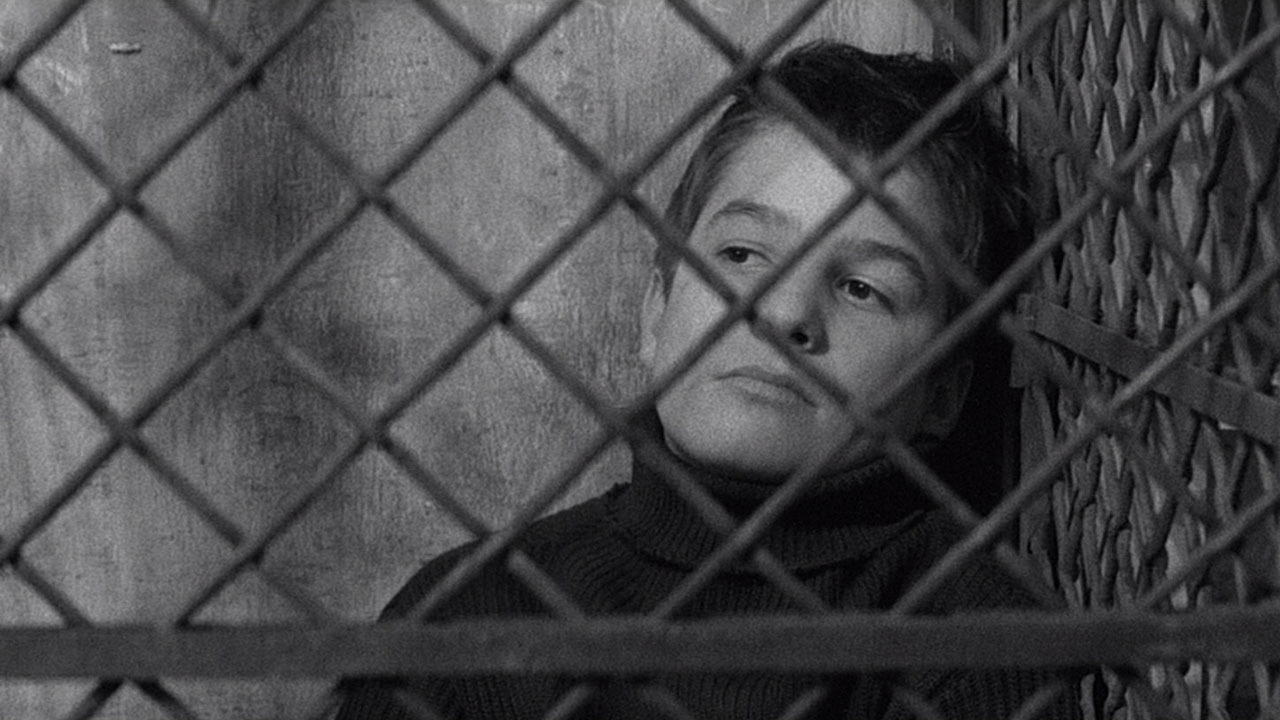

28. The 400 Blows (1959)

One thing which marked the New Wave was the facts of how literate and well-versed in film history (and many New Wave techniques were updated versions of innovations from the early days of cinema). More than a few New Wave film makers started as critics for the wildly influential Cahiers du Cinema.

One of the best Cahiers writers and subsequent directors was Francois Truffaut. Rising from a troubled childhood and youth, Truffaut had found salvation in film and wanted to help create a new, personal form of cinema, replacing the more industrial, factory made cinema the young film makers in that group despised.

After a few short subjects (also personal), Truffaut truly put his money where his mouth was with The 400 Blows. (The title is an expression which loosely means “to raise hell”.)

The names were changed, but the film essentially tells the story of the young director as he struggled with an unhappy home life (born out of wedlock and living with a confused mother and a man decidedly not his father) and heading towards reform school (as did Truffaut). The surprise was the such a potentially melodramatic subject yielded a film of such buoyancy, liveliness and naturalness.

The director seemed to be saying that he (and the main character) survived due to a life force which wouldn’t allow him to lay down and die and it all translates on film. The main character is named Antoine Doniel and played by a very young actor named Jean-Pierre Leaud.

Truffaut would return to the character five additional times before his premature death, always played by Leaud, whom the director used in other films as well (and who ended up with a major career of his own).

It was a totally unique collaboration and phenomenon in cinema history (only the recent US film Boyhood could match it). Though Truffaut would make many great films in a glorious career, The 400 Blows would remain among his best and most beloved.

29. Pickpocket (1959)

Robert Bresson closed out what may well be his finest decade (though the following two would be good as well) with a film many critics and historians consider not only his masterpiece but one of the greatest of all French (and world) films.

Inspired by (but not based on) the Dostoyevsky classic Crime and Punishment, Pickpocket examines the title character, a young man who has turned to crime, namely picking pockets for reasons the viewer must ferret out from intentionally oblique clues and observance of the character and his behavior and rather spare narration.

Michel (Martin LaSalle, one of Bresson’s non-professional “models”) is a conundrum: he is young, attractive, intelligent, poised but also insecure and tormented by things in his life which remain shadowy (especially his mother’s death, which seems to be a story unto itself). He could easily do better than a life of crime but he still pursues that path, though he has a conscience which won’t let him fully accept his lifestyle. Added into this is a difficult love for a young lady.

As ever, Bresson gets remarkably far inside by staying resolutely outside. Oddly, the deliberately uninflected, unemotional line readings and unexpressive facial expressions of the main character seem just right for a human being so alienated and removed from human experience.

Amazingly, the film comes to what very many consider not only the most emotionally powerful ending of any Bresson film but in any film period (and US director-writer Paul Schrader had no qualms about “borrowing’ it for his 1980 film American Gigalo, which, on the whole, couldn’t be much more different from this film).

One notable characteristic of this film is that it only runs 79 minutes. Bresson was never one to belabor things but, outside of The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), this is his shortest film and all the better for it.

Not a moment is wasted or extraneous and the film seems to run exactly as long as needed, no more, no less. Bresson films were never, and will never be, for everyone. However, if one can give themselves to this film maker’s work, the rewards are substantial.

30. Room at the Top (1959)

Just the fact of being one of the victors in a large scale war does not necessarily mean there will be much happiness thereafter. The British went through a lot of horror and hardship during World War II only to find things less than sunny thereafter. After a long period of deprivation and recovery, the British slowly began to realize that, well, their society had changed.

Brittan had, for centuries, been among the most rigidly class conscious of nations and the citizens generally knew their places, mostly decided by birth. The class to which one was born was the one to which they were expected to stay. After the war, those in the lower classes who fought and suffered as much, if not more, than any began to think that they had a right to more.

Also, these young people also were exposed to things outside of their own class during those years, There was also a bit a disenchantment when a Brittan which didn’t completely live up to billing. Thus what was known as the “angry young man” and “kitchen sink” schools of drama were created.

These movements, which took in literature and theater as well as film, wanted to show it all as it really was and wanted to focus on the less polite and affluent United Kingdom which had long been the subject of the nation’s films.

A key film in this development is Room at the Top, taken, significantly from a much acclaimed/discussed novel by British writer John Braine.

The novel tells the story of Joe Lampton (played on film by Laurence Harvey), a lower class young man who spent much of World War II as a prisoner of war, barely escaping with his life. He is just starting a new job at a factory in the bleak north of England as the story opens and he wants to move ahead to bigger and better. He sees a chance when he encounters the callow daughter (Heather Sears) of the rigidly classist owner (Donald Wolfit).

The girl has an attraction to him he plans to exploit ruthlessly. However, a complication arises when, while appearing in an amateur play, he commences an illicit relationship with Alice (Simone Signoret), the terribly unhappy French wife of a nasty local businessman.

The mature, worldly, womanly Alice is everything the naïve Susan is not the she desperately needs/loves Joe, though her love for such an ambitious climber is questionable. The characters are all set on a collision course which will have some tragic ramifications and will leave no one unscathed.

Directed by Jack Clayton, Room was a most unexpected hit, even in the U.K. It has a rather conventionally formal style yet the feeling is of a new era, though the story was not unfamiliar, even then. The execution, however, is flawless.

The direction, writing, and acting all register just the right notes. Harvey was never that great of an actor (even in his magum opus, 1962’s The Manchurian Candidate) but, being quite a hustler in his early years, he clearly understood Lampton and gave the one truly good performance of his career.

Trumping him, though, is Signoret, despite a paucity of screen time. Off screen, she nearly lost her longtime husband, Yves Montand, to Marilyn Monroe that year and sad desperation of a woman way too good to be subjected to such things must have informed her performance to the degree that her every scene comes off as a big one.

Though the film would be showered with Oscar noms (an anomaly for a non-Hollywood film in those years), the somewhat surprising Oscar (against heavy competition) which Signoret won was its major award (the script also won).

The film also set an odd Academy record when Hermione Badderly was nominated for best supporting actress…for a performance which runs a total of two and a half minutes (the shortest ever)! (And, no, it isn’t one big scene.)

Clayton, making his debut, was put on the map by this film and the 1960s would be quite good for him (The Innocents, 1962, The Pumpkin Eater,1964) but his own pickiness caused him to turn down several scripts which became big hits artistically and dramatically and lead to him being labeled “difficult”.

Sadlly, the main players also would have a few good years in the next decade before seeing their careers decline for various reasons. Still, they had one shinning moment and it set a new standard in this country’s film industry.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film,cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.