In the years just after the Second World War, cinema seemed to flourish in response to the new world order so fitfully being born. (Studying film history, it often seems that the worst of times stimulates the best in film makers.) It appeared that every nation of Europe and Asia affected by that conflict gave birth to some new movement in film.

These movements such as Italy’s Neo-Realism, France’s New Wave, Britian’s “Kitchen Sink” school, and the Czech Spring sought to break free of old and mostly artificial traditions and present a truer, more honest portrait of contemporary life using new and notaly less inhibited techniques. These changes started to show up in the 1950s, often stemming from long established directors yearning to break free or young film makers who had been film journalists or scholars.

While the new forms took root in that decade and would continue into the 1970s (pretty much dying off in that decade) it was truly the 1960s which saw the full flowering of these efforts. For those film lovers who remember that decade or those film students who came later, there was no time quite like that period.

These directors would often turn out one or more masterful films per year and it was exciting to be able to await the latest pictures by Bergman, Fellini, Trauffaut, Goddard and others or to find interesting films from new places. The following list wishes to stetch out that decade in Europe. It can not do justice fully to that time and some films stand for the body of work their creators produced during those years.

1. Rocco and His Brothers (1960)

The great Italian director Luchiano Visconti was a most interesting figure in cinema history. A titled aristocrat, he rejected that trappings of his wealth and privilege (and it’s mores, as, among other things, he was openly gay) for artistic pursuits with films which examined the dynamics of various Italian social classes. He would begin his career employing the gritty documentary style of Neo-Realism in studys of the working class and end up making films dissecting his native class in a style many likened to opera.

The one film which seemed to join the two halves of his career was Rocco and His Brothers, the film which inaugurated his finest decade. The narrative concerns a poor family from the country which makes its way to the city of Milan, hoping for a better life. Sad to say, Milan will prove to be too much for the already troubled family thanks to the griminess of middle brother Rocco’s boxing career, the brutality and greed of older brother Simone and the catalyst of Nadia, a woman both brothers desire and who is no better than a prostitute.

Many have found the plot a bit over-dramatic and the acting is somewhat uneven (the handsome Alain Delon, whom Visconti favored, gets by on looks while Katina Paxinou as the mother is allowed to go way over the top). However, the director has a superb feel for the setting of lower class Milan and the occupants of that sector in the Neo-Realist tradition, mixing it well with the dramatic style of a newer age in film.

2. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960)

British films often suffered from being very proper and adherent to stage acting, directing and writing for many years. During and just after the World War II years grittier fare started to appear (often in what is now called Brit Noir) but the real change took place in the late 1950s and 60s when a number of plays and novels were produced by mostly younger writers looking at the lives of working class British citizens who often felt anger and dissatisfaction due to limited funds, living condtions, and education joined with a lack of opportunity.

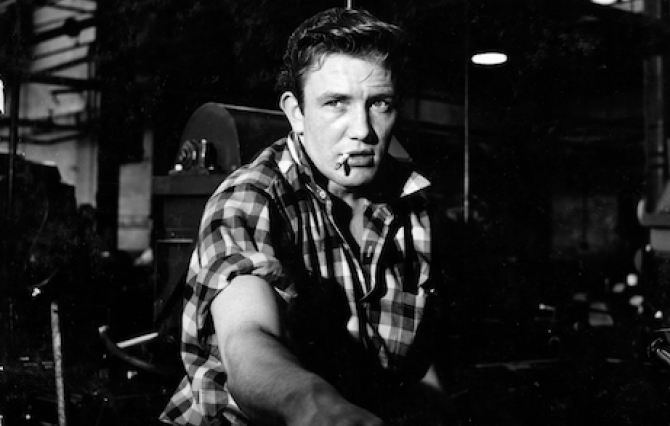

A key work of this cycle was the novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and the film which director Karel Reicz made from it. The film features stage actor Albert Finney in his first lead role. He plays surly factory worker Arthur who grits his teeth through his grinding dailey routine while wating for the titular time frame to come. When Saturday night comes its all cheap, noisey clubs, drinking, fights, and loose women (and Arthur is involved with a quite randy older married woman, expertly played by Rachel Roberts).

Arthur, deep down, knows this is no way to live and finds a promising relationship with a thoughtful young woman (Shirley Anne Field), though his environment and more than one mess he’s made will give him a tough time. All of this was a long way from the polite society British films often portrayed and, to the minds of many, all the better for it. As with all of the new film movements of that era, a greater level of reality was sinking in and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is a fine example of the British variety.

3. Peeping Tom (1960)

One of the glories of the traditonal British cinema was the team known as The Archers, Michael Powell (director-writer) and Emeric Pressburger (producer-writer). Though their unique films were big favorites many noted that there was a wild and unruly quality to them. After the pair went their separate ways in the Fifties, the British public soon enough found out which partner supplied that wildness quotient.

Often when film are controversial or shocking, later generations will find the shocking material quaint if not silly. Powell’s solo effort, Peeping Tom, is an exception to that status. In fact, with the common use of home recording devices in modern times, it may be more disturbing than ever. The film concerns a young focus puller (Carl Bohem) who has a most disquiteting hobby: he tracks and murders young women with a device which allows the women to see the reflections of their own murders as he records them on film.

That doesn’t sound so quaint, now does it? This theme is a lot for the modern era and it was much too much for 1960 (this film came out a short while before Psycho). Powell saw his whole career pretty much down go down the drain (though posterity affirmed him late in his long life). The picture is still extremely strong and distressing, all the more so for being skillfully made. Career-wise it was a folly but a most glorious one.

4. La Notte (1961)

After being promising newcomer in the Italian film industry for over a dozen years and having achieved some local success, Michaelangelo Antonioni hit pay dirt with the international art house hit L’Avventura in 1960. The Sixties would prove to be his decade with the almost half dozen of his films made during that period all enjoying great critical reputations with their cool, elegant, spare modern style and some achieved box office success.

Oddly enough, one of the best is now among the lesser known. L’Avventura and the two films which immediately followed were known as the director’s “alienation trilogy”. Each features sophisticated people in lovely settings mostly not enjoying the sweet life of the Italian upper class due to a central emptiness in that society and inside themselves.

Number three 1963’s L’Ecclipse is still well known but the somewhat neglected middle portion, La Notte, may well be the most incisive and telling of the three. A famous novelist (Marcello Mastroianni) is having a great day with the publication of his latest book and the lavish party set to celebrate the event being given by his publisher.

The day is so overwhelming that he barely registers that his old friend (Bernhard Wicki), whom he visits in the hosptial, is dying. He doesn’t really register at all that his stylish and smart wife (Jeanne Moreau) is majorly upset about something. The day gives way to the night and a series of empty revels and it becomes obvious that the couple is in deep trouble, in no small part due to the husband’s superficiality. The wife’s revelation of the source of her distress suprises the man but it won’t surprise anyone else paying attention.

Part of the superiority of this film is the fine acting of the leads, in contrast to the lesser known actors the director often favored (such as the beautiful but limited Monica Vitti, who shows up here in the supporting role of a deeply aimless and wealthy young woman). Moreau in particular is a treasure as she was not only perhaps the finest European film actress of her time but one with an uncanny instinct for working with the best of directors.

5. Viridiana (1961)

Spain’s Luis Bunuel, perhaps the greatest surrealist in film history, had a most unusual career. As a young director he had joined with then evolving artist Salvador Dali (the art world’s great surrealist, arguably) to astound the cinematic with the 1928 short subject Un Chien Andalou and then greatly offend the Catholic hierarchy with 1930’s L’Age D’or to the extent that Bunuel was prohibited from making films in any Catholic country…forever!

He spent years wandering and working at jobs such as one in the publicity department at Warner Brothers (Spanish language division) before finally slipping into directing again in the Mexican film industry. He labored there for over a decade and started creating masterpieces which couldn’t be ignored and was eventually able to get back to working in Europe (France and Spain) in time for the Sixties, his finest decade.

Viridiana, one of his best, again tackles his usual themes concerning the foibles of the upper classes, religious hypocrisy, and lots of kinky sexual obsessions, all done in the director’s trademark straight-faced immaculately formal style. The story is one that should be familiar to the Bunuel faithful. Young Viridiana (Sylvia Panel)is an innocent young novice in the kind of suspect convent Bunuel would typically create.

The lovely young woman is summoned to the estate of her long unseen uncle (Bunuel regular Fernando Rey), who is obviously one major degenerate, albeit one with great élan. However, his money and position convince the nuns to ignore that in letting the girl go to him. What follows are lots of skillful swipes at the church and the aristocracy and exploration into some wild fetishes to comment on it all. Bunuel had returned to Europe in style.

6. Divorce, Italian Style (1961)

Surveying this list, the reader may be struck with the fact that the notable European films of the 1960s weren’t a barrel of laughs on the whole. Well, neither was life in Europe during those years. However, the Italian film industry seemed to find some adroitly rendered humor in the manners and mores of its country.

One of the decade’s most delightful comic hits was this gem from director Pietro Germi, which was so popular in the U.S. that it won an Oscar for it’s script and a nomination for the splendid performance of lead Marcello Mastroianni. Here the great actor and star slyly plays a decadent middle aged modern noble who has fallen in love with a young and lovely distant cousin (Stefania Sandrelli) and wishes to marry her.

Too bad that he’s long married to a woman (Daniela Rocca) he’s always found repulsive (might have something to do with her mustache), but who his family decreed he married for reason having nothing to do with amour. Unfortunately, with Italy being the seat of Catholicism (and very old school in those times), divorce is a big taboo.

How can he rid himself of her and still manage to keep the family honor and (more importantly) property? Well, love and decayed aristocracy can find a way. Mastroianni had long been considered a major dramatic actor and a most dashing one but this one showed the depth of his talent and willingness to sacrifice his matinee idol looks for a fine script and a talented director.

7. Jules and Jim (1962)

The young critics of the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinema revolutionized both film criticism and the way film history was viewed with their perceptive views on the subject and their insightful looks back at the best of cinematic history and how even old cinematic devices could be applied in a new fashion. The proof of the validity of their work was the fact that so many of the those young men became directors in their own right and virtually all of them had notable careers.

Perhaps the brightest of the bunch, certainly the most beloved, was Francois Trauffaut, a one time juvenile delinquent by his own admission, who had found salvation in film. He had an extraordinary career with very few misses (sadly abbreviated, along with his life, by a brain tumor while in his fifties). His films were marked not only by love of cinema but a deeply compassionate understanding of humanity.

Though his entire career as worthy, many think that he never did better than his first three films, all masterpieces. His autobiographical debut was The 400 Blows in 1959, followed by Shoot the Piano Player in 1962 but to many the greatest of all was number three, Jules and Jim.

The film, which starts just before World War I and ends just before World War II, tells the story of two friends, French Jules (Henri Serre) and German Jim (an excellent Oskar Werner), who build a solid friendship based on their artistic temperaments and exuberance for life. However, both become captivated by Catherine (Jeanne Moreau), not a beauty but the most intriguing and enigmatic of woman. Both men will share her affections and the game of love they play will go on way too long, with tragic consequences.

The director is at his masterful best here but the film truly belongs to the leading lady. Moreau had championed the director and contributed financially and with a brief on-screen cameo to his debut. This was her reward, her finest hour in a rich career. For all the film’s other virtues, if she had not risen to the challenge, it would all have been for nothing. She and the film turned out great.