8. Knife in the Water (1962)

The eastern European nations which ended up becoming the Soviet Bloc were generally considered sad and limiting places for many years after the end of World War II. However, there were stirring of freedom, including the arts, in the 1960s (all too soon crushed militarily). One big surprise was a film which appeared out of almost nowhere by a young Polish film maker who had never before created a feature length film.

The director was Roman Polanski and his film, Knife in the Water, was a suspense piece driven by character, having nothing to do with politics. A successful couple in early middle age is driving to their yacht for the weekend. They encounter an attractive young man hitchhiking and pick him up, asking if he’d like to hire on as their deck hand.

During the outing it becomes apparent that the marriage is suffering a serious case of the blahs, that the woman is rather taken with the young man, and that the husband feels the need to prove his superiority and manhood. The results end up tense indeed. Skillfully shot in black and white with one major set and three actors of no great repute, the end result was deemed to be as worthy as the best of suspense master Alfred Hitchcock.

Many voiced the opinion that young Polanski needed a bigger venue than Poland and he agreed, defecting shortly thereafter, making this his only feature filmed in his homeland. The world would soon hear from him again.

9. Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

Russia’s Andre Tarkovsky earned a place in the pantheon of great film makers on the basis of only half a dozen films made during a foreshortened life plagued with political stumbling blocks and the long periods of time needed to set up his lengthy and complex films. Though not as intellectually ambitious as some of his later films, his autobiographical debut, Ivan’s Childhood, is held in esteem every bit as high as the others.

The film, plain and simple, tells the story of a young boy trying to grow up and survive under mightily adverse circumstances, namely World War II being furiously fought in his own back yard and he himself being conscripted to serve at an absurdly young age.

Always among the most cerebral of film makers, it is not surprising that this film is a highly sensitive and cinematically imaginative telling of how Ivan came of age in a time which happened to be quite difficult. The imagery and adroit choice of shots and angles, combined with an excellent script, helped to mark Tarkovsky as someone to watch.

10. 8 ½ (1963)

Italy’s Ferderico Fellini had been making films since his 1948 debut, co-directing Variety Lights (he had been a writer up until that time). He had directed seven more films during the remainder of the 40s and into the 50s and though he had his hits, 1959’s La Dolce Vita, a pointed, though now dated, look at Italy’s spiritually empty jet set, became his biggest international hit, one acclaimed for the uncanny images, at once fantastical and hyper-realistic, which are still known as the director’s trademark. He was all set to enter the big time and then…nothing.

Everyone wanted not just another film but a big one and Fellini had nothing to offer for he was good and blocked creatively. After a long period he did make a film about a noted film maker who can’t think of an idea for a new film after having a big hit, Yes, 8 ½ is a film about the making of itself! To some it was self indulgent, to others brilliant.

One can’t argue that it is quite well made with that carnival atmosphere and surreal clown like faces and phantasmagorical settings Fellini favored. Mastrioanni, his La Dolce Vita star, returned as, essentially, the director himself and gave one of his great performances. Complementing him are a stunning array of actress playing the many women of various descriptions who fill the director’s life and comment on his mental state.

Included are Anouk Amiee (another La Dolce Vita star) as the director’s long suffering wife and star, Sandra Milo as his woman on the side, Claudia Cardinale as an actress the director is sure will be his muse, and cult star Barbara Steele as his producer’s inappropriately young intellectual girlfriend. It was a neat trick and another big hit but one which could only be pulled off once. Though Fellini would have some other successes, 8 ½ would mark the end of his great period.

11. The Silence (1963)

Ingmar Bergman had been writing and directing films in his native Sweden since the mid-1940s and was widely acclaimed in his homeland, which had been in the cinematic doldrums since its golden days in the silent era. He broke through to international fame in the mid-Fifties, which set the stage for his greatest decades, the Sixties During those years, Bergman’s intense psychological dramas of conflict and self-examination in the face of spiritual crisis reached a new level of purity and simplicity.

Though his style would modify with the progression of the decade, there was no mistaking a Bergman film for any other. Among his noted achievements in the Sixties was a trilogy of films exploring characters moral dilemmas in the face of a faltering belief in God.

The titles include Through A Glass Darkly (1961) and Winter Light (1963) but the best remembered may be The Silence. The story concerns two rather mismatched sisters (Gunnel Lindblom and Bergman regular Ingrid Thulin) who are travelling together with the young son of one of the women. The one sister is promiscuous while the other is quite ill, preventing her from making any of the human contact she so desires.

The two seem to have no sisterly feelings and they are momentarily stuck in a country in which they don’t speak the language. The women slowly start to feel a greater isolation and feel that they have been deserted by God (thus, His silence, referenced by the title). The film has the clean, clear probing style accented by unusual but realistic details which marked Bergman at his best.

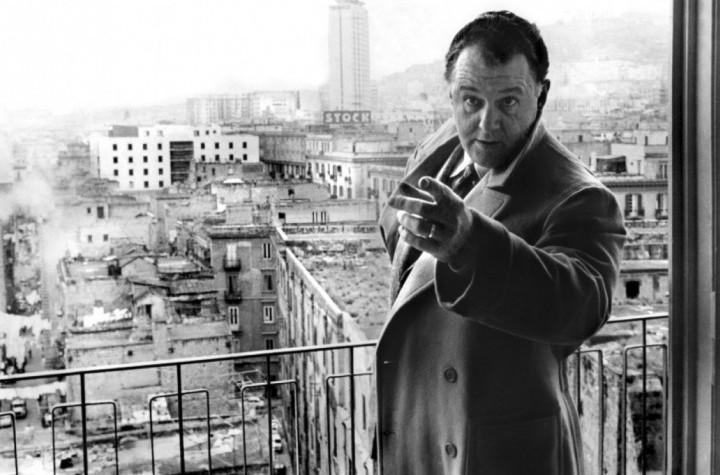

12. Hands Over the City (1963)

Though it has never been particularly well known by even the art house audience, Italian director Francesco Rosi’s Hands Over the City stands as one of the best films of its decade. Rosi was committed to making films which explored political topics (famously with the docudrama Salvatore Guliani) and this film was one of his very best.

Starring American film actor Rod Steiger, the film centers on a construction company (owned by Steiger’s character) which has a most cosy relationship with the local government in Naples. Unfortunately, due to the company’s shoddy, cost cutting methods in building a structure it was allowed to build due to graft collapses.

This happens just before a local election and all concerned are doing whatever it takes to shift blame. This film is a smart look at a system hopelessly corrupted with no justice for the victims (in this case, those in the disastrous building). This is a complex and ably crafted film which may not be a crowd pleaser but is superb.

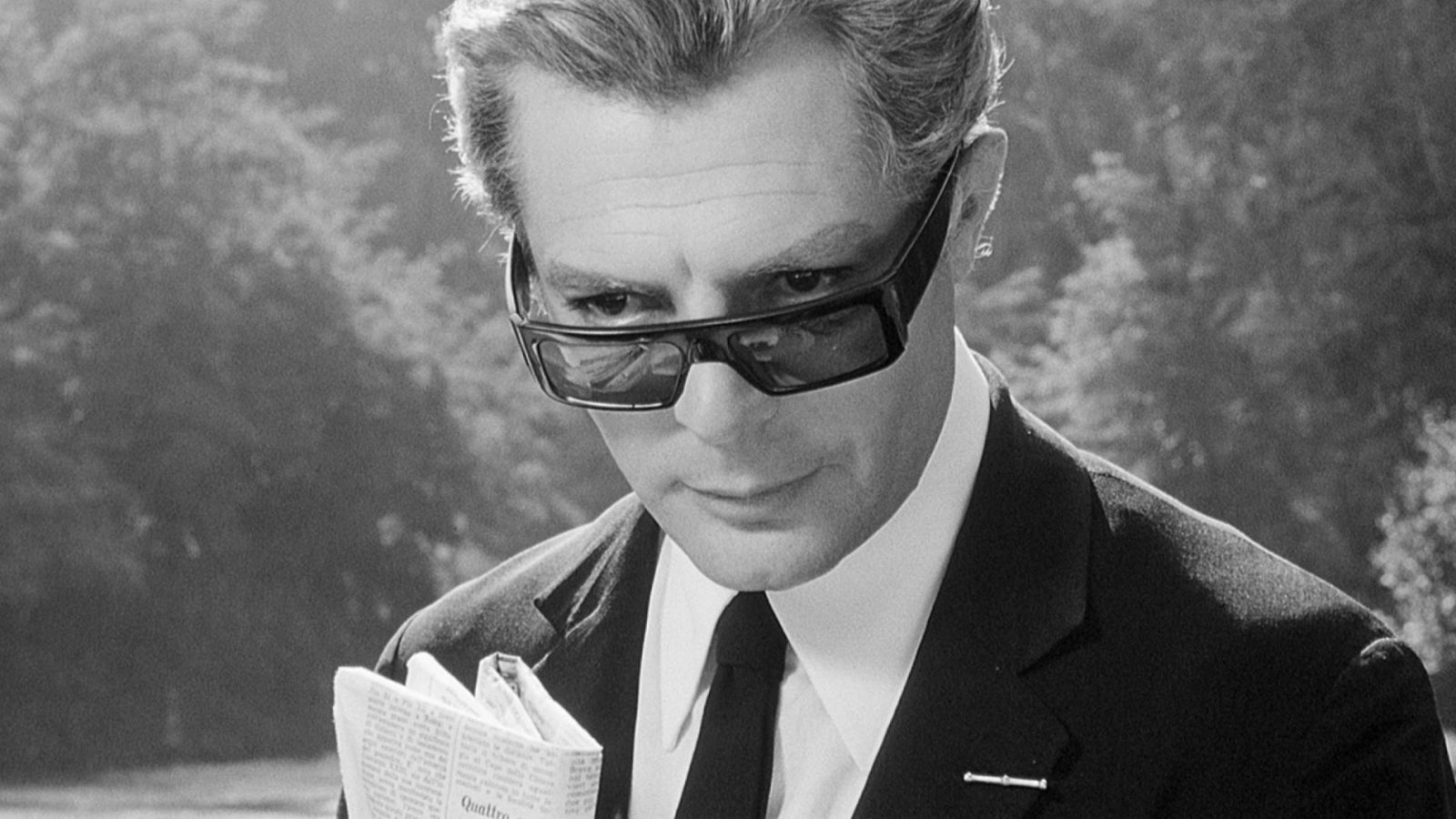

13. The Servant (1963)

American director Joseph Losey was one of the many forced to flee the U.S. in the face of being blacklisted in the early 1950s. He fled to England and found a creative freedom he hadn’t known in Hollywood. Though the blacklist ended, he never returned to America.

Losey had a unique understanding of British social mores and he was aided in his portrayals of these situations by the distinguished playwright Harold Pinter (a fine screenwriter, though none of his own great plays ever really made a great transition to the screen). The two made a number of notable films together and it would be difficult to pinpoint a masterpiece in the group but The Servant caused a great stir at the time of its release.

Taken from a short novel by Robin Maugham, The Servant sees a wealthy, callow young man (James Fox), who is setting up house in a trendy part of pre-swinging London, hiring a seemingly quite respectable manservant (Dirk Bograde) to manage the domicile. He misses the rather sinister undertones the man gives off and allows him to insert his “sister” (a young Sarah Miles) as a maid into the home, in an effort to entrap the gentleman.

However, the entrapment ends up going in a most unexpected direction. To call this film moody would be the greatest of understatements but this quality conjures the diseased atmosphere the director and writer are aiming to explore. They are aided by brave performances from the younger players but, especially, from Bogarde.

After a most professional but rather undistinguished career in the 1950s, he had broken into a different dimension after this film and the social thriller Victim (1961), films with gay themes at a time when homosexuality was a most punishable crime in the U.K. This set the stage for Bogarde to become one of the best film actors of the Sixties European film scene.

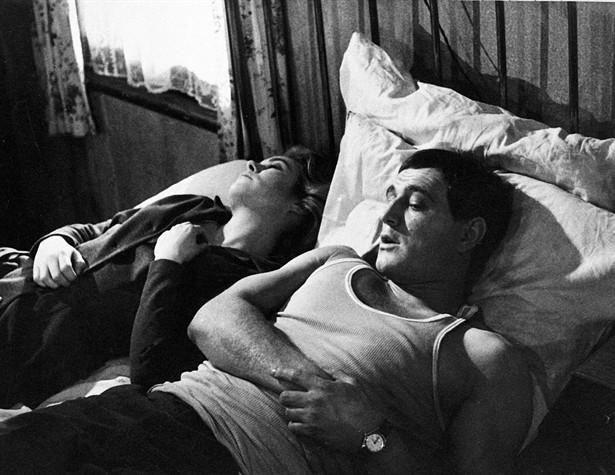

14. This Sporting Life (1963)

Lindsey Anderson was one of England’s best film critics in the Nineteen-Forties and early Fifties before becoming an excellent documentarian. In the early Sixties he was ready to branch out into feature films, though his idea was to become a producer.

However, he was persuaded to take the reins as director for an adaptation of British author David Storey’s acclaimed novel This Sporting Life, an examination of the rough world of professional rugby, framed through the eyes of a former coal miner who supposedly traded up when he entered the sports arena.

Filmed in sharp widescreen black and white, the film had a very gritty feel to it, thanks in part to the casting of rugged Richard Harris, an excellent Method actor, and Rachel Roberts as the landlady, repressed every way but sexually, with whom he has a most unsatisfying affair. It was an incisive debut and lead to a sporadic but quite brilliant career for the director.

15. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

France’s Jacques Demy was a truly unique director who concocted fable like films which were often interconnected, creating the impression that they exist in a universe all their own. The high point of his popularity was what may be the most specialized of all his films (and that’s saying something). Working for the first time in color, rendered in lush pastel tones, Demy created a tragic romance, all performed in song.

The story centers on two exceptionally attractive young lovers (Catherine Deneuve and Nino Castlenuovo) who are quite blissful, though the young man is about to leave his job as a mechanic to join the army and go to Algiers. The young woman, who lives and works with her mother in their small umbrella shop, gives herself to the young man and becomes pregnant.

He neglects to write or get in touch and the heroine becomes susceptible to the blandishments of a suitor, found by her mother, so smitten that he will accept the child of another in order to possess her. (The character of the suitor had originally appeared in Demy’s debut film, 1960’s Lola.)

This film could have gone so wrong in so many ways but it misses every one of them. The beautiful leads and the lilting Michel Legrand score, along with excellent visuals, all deserve praise but it was Demy who had the magic gift of not only rendering this story in a highly palatable way but created a work which makes the viewer feel elated, though the story is very sad.