24. Playtime (1967)

While the Sixties saw many promising new talents appear and some established ones flower, some others would wind up their prominent careers. France’s Jacques Tati, along with the later French actor-director Pierre Etaix, was the last of the great silent clowns, though he didn’t release a film until Jour de Fete in 1948!

There would be little to no dialog in his films and he himself never spoke. He almost always played his trademark character, the reserved, humane, and owlish M. Hulot, forever attempting to fit into society on his own terms. Tati also wrote and directed all of his films and only managed to create five features and a couple of TV projects as a career total. His undeserved Waterloo was Playtime, a wildly expensive film which could not earn back its cost.

The story has Hulot trying to make his way in an ultra-modern Paris and finding love with an American tourist. The joke is that the glory of Paris is now covered up with modern structures and its old ways subsumed by modern mores. (All the great monuments of Paris past are only fleetingly seen in reflections.) Why did it cost so much? Well, none of what is on screen is the real Paris but a stylized recreation built in the studio at great cost. It was a folly, but a grand one.

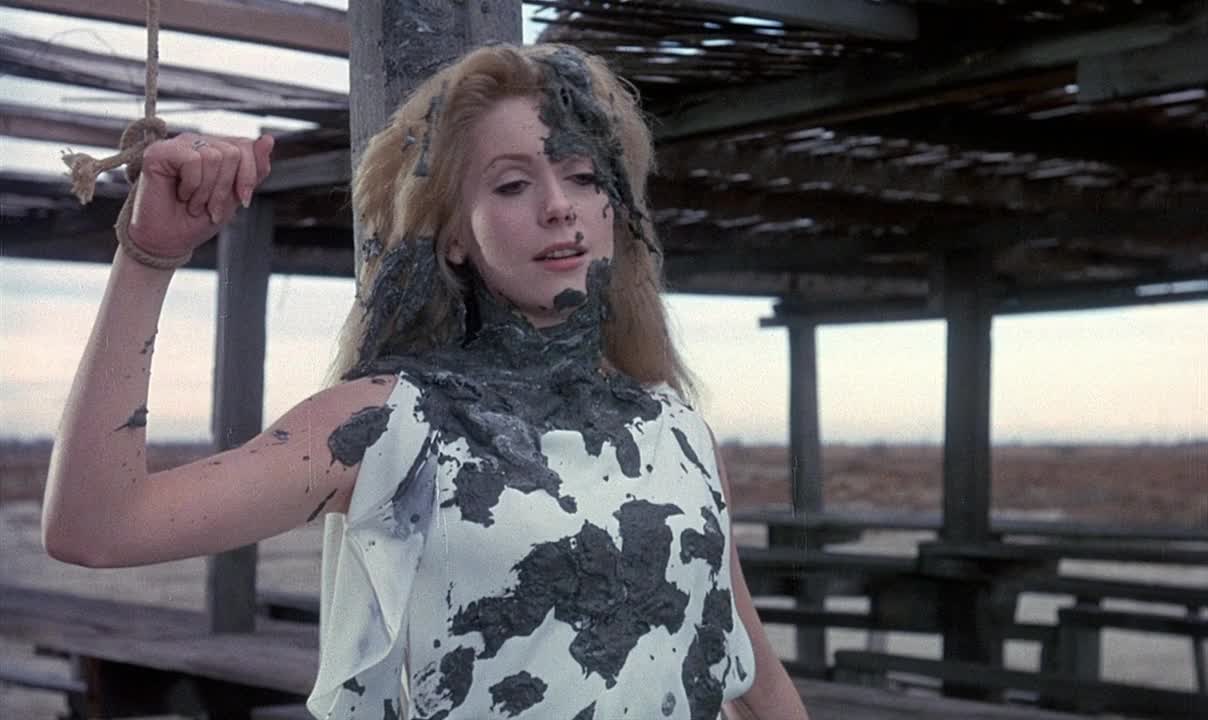

25. Belle de Jour (1967)

Once Luis Bunuel made it back to Europe, he was determined to make up for lost time. While many directors, even great ones, wind down at the end, he had stored up ideas he finally was able to unleash late in life. Of his several later masterpieces, many consider Belle de Jour the very best.

The beautiful Severine (Catherine Denueve, again finding a great director) has it all with a handsome and loving new husband who has a promising career, a lovely home, and a place in high society…and finds it just isn’t enough. By a wild set of circumstances (logical in Bunuel’s world) she ends up as a prostitute in a upper class bordello, but only during the daylight hours while her husband is at work. Her hidden inner fantasies are freed, but a price will have to be paid.

Once more the director perfectly impales the foilbles and pretensions of society and presents more fetishies than many ever knew existed. He also uses the leading lady’s haughty and impassive beauty to stunning effect (as he also did in Tristana, another great film). In Bunuel’s case autumnal was a complimentary term.

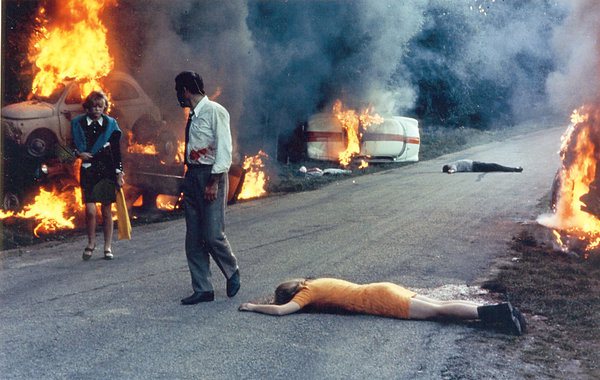

26. Weekend (1967)

Much like Groucho Marx’s character Rufus T. Firefly in 1933’s Duck Soup, whatever anyone had French director Jean-Luc Goddard seemed to be againist it. His films weren’t so much films as anti-films, dissecting one genre after another. Goddard has also been in the Cahier du Cinema crowd but he did not appear to love cinema’s past nor society’s present. To the surprise of absolutely no one, he presented his ultimate vision of how low he thought it all was and is with the savage social satire Weekend.

The loose plot has an amoral couple engage in a vauge plot to kill a relative for money but before it ever gets off the ground there are nightmarish traffic jams, wild accidents, casual murders and urban guerillas who turn out to be cannibals.

Obviously, this is not to be taken realistically but the film did show the limits of the director’s highly individualistic point of view. He showed great force and imagination but it was a phyric victory as everything he has made since seems anti-climatic (the closing titles annouces the end of the film then the end of cinema).

27. My Night at Maud’s (1969)

Many of the great European directors of the Sixties created films for specialized audiences but the king of them all may be yet another Cahier’s graduate, Eric Rohmer. A typical Rohmer features a group of vocal people of more than adequate intellects caught up in an intriguing situation with one real incident of great importance taking play and having all concerned talk it all out…at great length.

Depending on one’s views a Rohmer film may be Heaven or Hell. The hub of his career was a cycle of films dubbed the “Six Moral Tales”. Starting as amateur efforts these films confront moral dilemmas which the characters must navigate with an uncertain moral compass. The first of the tales of reach a large audience was My Night with Maud. In this film Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintigant) meets the intriguing Maud (Francois Fabian) through a friend and finds endless interest in her many challenging views.

This leads to him spending a night full of possibilities at her home…but he is deeply committed to another. This could be a stock situation but the characters behave as real people and the direction of their course is far from certain. Not everyone cared for this or subsequent Rohmer efforts but there have been many who found the films as intriguing as Jean-Louis found Maud…and about as infuriating at times.

28. Z (1969)

Greek-French director Costa-Gavras is unique in that he has made a career of creating films with overt political themes. Some of those films tended to come across as heavy-handed but, at his best, he could make political issues quite exciting. His breakthrough and still most memorable film is the Oscar winning political thriller Z.

The film was taken from a novel which told a slightly fictionalized version of the events which helped lead to the junta which sweep the Greek military to dictatorial power. A liberal Greek official (Yves Montand) is murdered in a manner cleverly designed to look like an accident.

A young prosecutor (Jean-Lous Trintigant) takes on the investigation with the help of a young photojournalist (Jacques Perrin) and comes within striking distance of victory…then political fate intervenes. Through the director had a strong message, it was posited in the form of a thriller and ended up becoming a big box office and critical success world-wide.

29. Les Biches (1969)

The most prolific of the Cahier’s group was also, in many ways, the most conventional minded. Claude Chabrol has often been called the “French Hitchcock” and the term is not incorrect. His career spanned a half century and included almost as many films as Hitchcock himself (remarkable considering the differences in the eras in which the two men worked). With such a large output its not surprising that some were better than others.

Chabrol was at his best in the late Sixties and early Seventies and Les Biches is one of his most memorable films of that era. Wealthy, mature Frederique (an excellent Stephane Audran) more or less buys waif-like street artist Why (Jacqueline Sassard) and takes her to live in a secluded villa. The two eventually become interested in local architect Paul (Jean-Louis Trintigant, yet again).

Since they agree that neither is sexually excited by him, they ask him to come stay with them at the villa. However, nothing is ever so cut and dried and events drift into a perilous state. Though there is plenty of suspense, Chabrol invests the film with more human emotion and drama then his British counterpart often summoned and shows Chabrol at his best.

30. Women in Love (1969)

The great British novelist D.H. Lawrence was so daring an artist in the context of the early 20th century that it took many decades for the cinematic world to become liberated enough to film his books. Outside of a highly regarded 1949 version of Lawrence’s atypical short story The Rocking Horse Winner, Lawrence fans would have to wait for the Sixties to bring film adaptations of his work.

1960s acclaimed Sons and Lovers now looks a bit constricted but the next major adaptation, Women in Love, coming at the other end of the decade is quite another story. Ken Russell had started as a ballet dancer before becoming a director first with a group of odd and artistic TV biographies of notable creative artists and then segueing into films.

Women in Love, the story of two liberated British midland sisters and the men they uneasily fall in love with (who also have a form of loving for each other), was his third film and big breakthrough. Highly sensual and bravely sexual, Women in Love was quite a conversation piece in its time (due in no small measure to a still infamous nude wrestling scene between leading men Alan Bates and Oliver Reed).

The excellent Glenda Jackson, new to film from the Royal Shakespeare Company, took at the Best Actress Oscar for her bold work as the more demanding of the sisters (the other was played by TV actress Jennie Linden, who had a limited career). Today the films looks a bit over the top in a late Sixties way but it still impresses as a vital and cinematic adaptation of a literary classic.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film,cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.