6. L’Eclisse (The Eclipse, 1962)

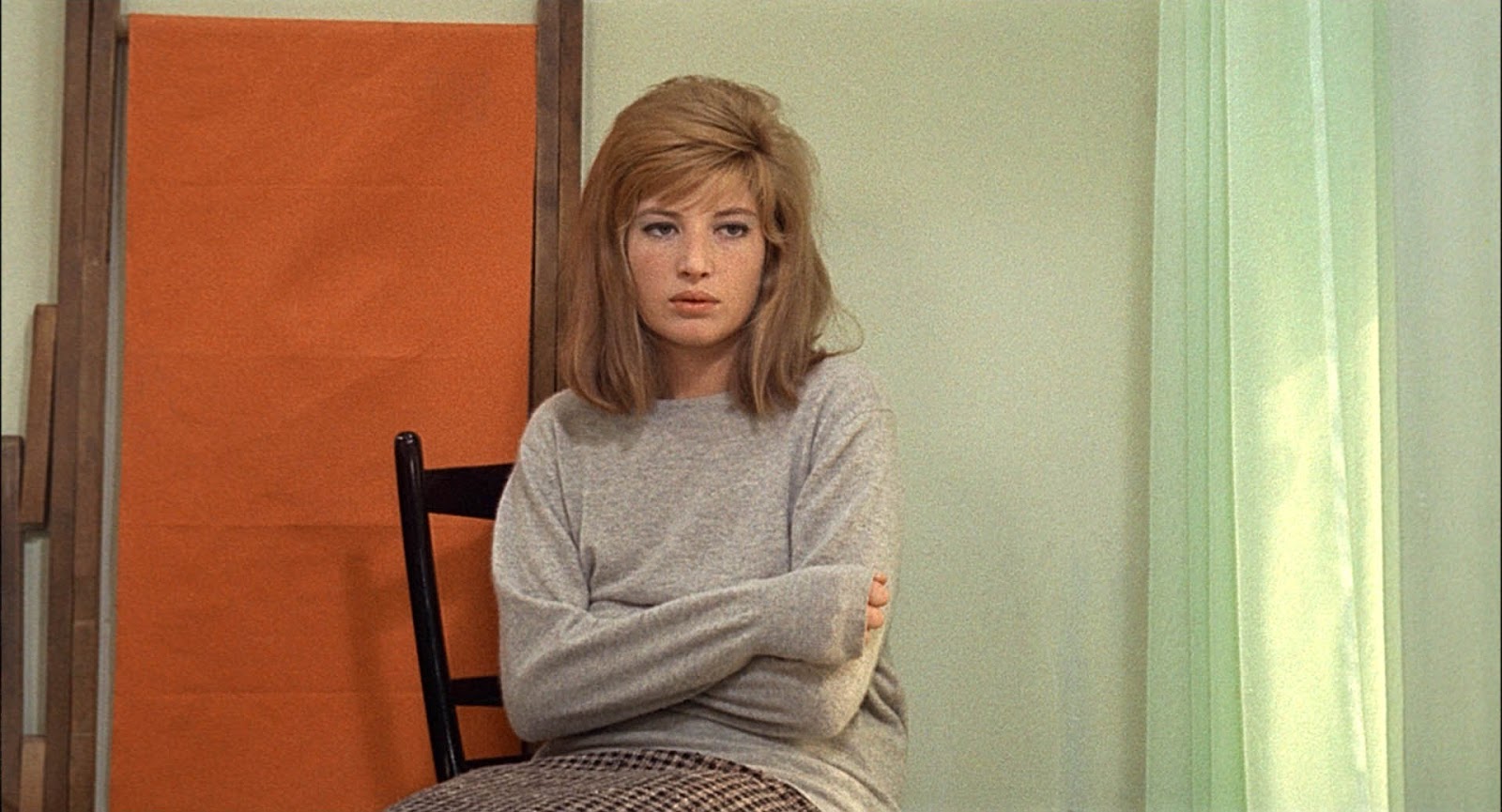

We first see Vittoria (Monica Vitti) from the back, an Antonioni signature. She is then shown looking at objects through a wooden frame she holds in her hand, an ashtray and what looks to be a small sculpture. These opening shots create a distant quality to her character. She looks bored and the man she is with, Riccardo, looks angry. She is determined to break off their relationship. She tells him she brought a translation of a German article for him and that she’s sorry she can no longer do this type of work for him. He asks her if it’s because she doesn’t want to get married or if she no longer loves him. She says she doesn’t know.

Vittoria walks for awhile, a conspicuous mushroom-shaped tower in the distance. Riccardo appears behind her in a car, apologizing for not offering to come with her. She tells him to leave her alone. He gets out and follows her. He asks her if she wants breakfast but she says she’s not hungry. She says it was a terrible night for her too and apologizes. He says they should call each other then, but then changes his mind and leaves.

One day Vittoria visits the chaotic crowd at the stock exchange to see her mother. We see Piero (Alain Delon) eavesdrop on some insider trading and run off frantically to buy stocks. Piero is her mother’s stockbroker, and he introduces himself to her. It is announced that a colleague died from a heart attack and they are asked to observe some moments of silence. As they stand there phones keep ringing and Piero looks over at Vittoria and tells her “One minute here costs billions,” seeming not overly concerned about his colleague’s death.

After some hesitancy, Vittoria and Piero begin a relationship. They have developed a ritual of meeting each other at the same place, a construction site. The most striking visual motif in the film, found from the design of the opening credits to the street near Vittoria’s apartment and other places, including one of the paintings of Vittoria’s ex boyfriend, is the motif of white lines. They are not just aesthetic flavouring, but are lines between people, lines of power, lines where life transforms and cannot return to its previous state, and ultimately, the line in which the well-being of the entire world hangs in balance.

What makes L’Eclisse a supreme masterpiece is not only the poignancy and surprise of its last segment, but how in this small space of time what appears to be so private, including the events of the other films of the trilogy, resonates so profoundly as allegory, ultimately drawn into, and then validated by its historicity.

7. Il deserto rosso (Red Desert, 1964)

The opening credits flash across a soft focus industrial landscape of towers, machinery and flare stacks. A haunting voice begins singing, the music by Giovanni Fusco, sung by Cecilia Fusco. But electronic music is also in the background, composed by Vittorio Gelmetti. It is a striking counterpoint which evokes some of the central tensions found in Il Deserto Rosso. After the electronic component dies down, the voice becomes louder and machinery noises from the background setting are introduced, the voice intensifying to a shriek, then receding again into its haunting melody.

Giuliana (Monica Vitti) walks into the industrial site hand in hand with her son Valerio. She is in green, he in yellow, a bit of colour in an otherwise extremely grey setting.

She is fidgety and agitated. She approaches a man and asks to buy his sandwich, and then walks towards some shrubs which are half-stripped and dark, and eats there in a way that looks famished and paranoid. Antonioni painted these shrubs to get the desired effect. Il Deserto Rosso was his first colour film and the colour component of it is perhaps more important than in any of his other works.

All around Giuliana there are mounds of black dirt with rubbish mixed into them. Her son runs to find her and they resume walking. We then see Giuliana’s husband Ugo (Carlo Chionetti) at work in the plant speaking with Corrado Zeller (Richard Harris) who has traveled there on business. Giuliana comes into the plant and Ugo introduces her to Corrado.

Giuliana leaves, saying she will wait in Ugo’s office. Ugo explains that in rainy weather Giuliana recently had an accident, and that she hadn’t been driving for very long. She was not badly hurt, but it had been quite a shock to her. He says she spent a month in hospital and that “the gears still don’t quite mesh” and that she wants to open a shop.

It soon becomes clear that Giuliana is intensely neurotic. After he comes to see her in her empty shop which has rows of paint cans lined up in it with a wall of blocks of test colour, Giuliana and Corrado strike up a friendship. She says that she does not know yet what she will sell and we find out that Corrado will be moving to Patagonia. They are both ungrounded, restless figures who are not sure what they want in life. They blend seamlessly into the film’s aesthetic and their attraction on screen seems palpable and natural, their pale complexions looking much like the liquefied fog or steam which is so prevalent throughout the work.

Containing some of the most erotic moments in cinema, Il Deserto Rosso also simultaneously portrays a failed eroticism in the context of the poison of modern existence. What we see of the characters’ attempt to consummate their desire is hysteric, verging on bathos. Their passion it seems is like a banquet laid out before them which they can admire, but cannot really partake of.

In its palette, which has the utmost integrity and a very stark beauty, it is a very grey and yellow film, the yellow often mixed into other colours in the fabric of clothing, or ostensibly in pools of poisonous water or sulphurous smoke emitted from chimneys. This integrity of the visual element of course makes for a very artificial cinema.

Regarding Antonioni’s manipulation of colour in his settings, which varied from painting trees to grass to whole city blocks, Ingmar Bergman said that he “never properly learnt his craft. He’s an aesthete.” Although an obsession with aesthetic can undoubtedly lead to less relevant filmmaking, it is undoubtedly a harsh criticism. Roland Barthes refers to the trajectory of Antonioni’s work as having a “double vigilance”, highly universal and personal at the same time

. It is, he says, plastic, historic and neurotic at once. These varying facets constitute its totality, its social significance found in what these “levels” evoke in their interchange. The mastery and ingenuity of formal elements does not negate any content in Il deserto rosso, but on the contrary, only makes it that much more of a masterpiece.

8. Blowup (1966)

Thomas (David Hemmings) is a fashion photographer leading a glamorous life most men would envy in “swinging sixties” London. When we first see him, he is coming out of a shelter for homeless men, which indicates despite this lifestyle, he is perhaps not without sympathy and has a perspective beyond the realm of high fashion. He is shown photographing Veruschka and other high fashion models, but becomes frustrated and leaves, taking his camera with him.

Walking in the park, he spots a pair of lovers and begins to photograph them. The woman, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave) spots Thomas and demands the photos, eventually biting him. Jane runs off and is shown receding across the park as Thomas takes more photographs.

When he returns home Jane runs up to breathlessly. She somehow found out where he lives. He asks her up and they listen to music for awhile. They seem attracted to one another and Jane says she’s nervous and asks for water. She sneaks off with his camera, only to find him waiting for her downstairs. She comes back up and takes her shirt off. He tells her to get dressed, and that he will cut out the negatives she wants. He gives her a roll of film and they kiss. The buzzer rings. Jane leaves and he develops the real negatives.

Examining them closely he finds what seems to be someone looking out from the trees with a gun. In another blowup Jane appears to be looking at something off camera. He hangs up various shots on his apartment walls. Jane and her lover look worried, quite a contrast to how everything appeared from a distance. Blowing up the one image further, we discover a gun in the man’s hand. He also finds an image of what appears to be a body on the ground.

A captivating mixture of high art and pop art, Blowup is a commentary on the limits of observation and perhaps more than anything, the pervasive and insidious nature of human negligence. What is ingenious about it is how the camera itself is used as a medium to explore these two kinds of flaws in existence, the one being epistemological, and the other, moral. An unconventional thriller which has had widespread influence and regarded by many critics to be a masterpiece, it has a marvelous diegetic jazz score by Herbie Hancock and an appearance by the Yardbirds.

Antonioni spray-painted large swathes of grass in the park green for this film. “I got effects you cannot get in the laboratories” he said of what he did. He also painted trees in the park and changed the color of a whole city block by building a white replica façade on scaffolding. It is the first of three English-language films he directed for producer Carlo Ponti.

9. Zabriskie Point (1970)

The camera pans a crowd of student protesters, moving in and out of focus. The students wish to go on strike, but it is clear that they lack a unified vision. There are racial tensions within their group of activists. One student says you have to speak to people in their own language. If that language is guns, then you have to use guns. “I’m willing to die too” says Mark (Mark Frechette) “but not of boredom” then leaves. The students get angry at this. “If he wants to be a revolutionary, he has to work with other people” one says angrily.

At a protest at the university a cop is killed. Mark had pulled a gun from an ankle holster but it is unclear from the timing whether or not he is responsible. He flees the scene anyway, and ends up stealing a plane and flying it to the desert. There he meets Daria (Daria Halprin), a young woman avoiding her boss. They drive in her car to Zabriskie Point, an ancient lake bed east of Death Valley, and make love in the valley which is surrounded by badlands.

Although widely dismissed by critics and viewers, Zabriskie Point has a beautiful aesthetic, a great non-diegetic soundtrack including Pink Floyd and the Grateful Dead, and is an eloquent statement against modern consumerist culture.

The scene at Zabriskie Point itself, where Mark and Daria make love and around them the badlands come to life with other people coupling and in orgy understandably created quite a controversy at the time, and admittedly is perhaps a gratuitous and juvenile male fantasy. The filming was investigated by the U.S. Department of Justice and parts of the scene were censored in Italy.

10. The Passenger (1975)

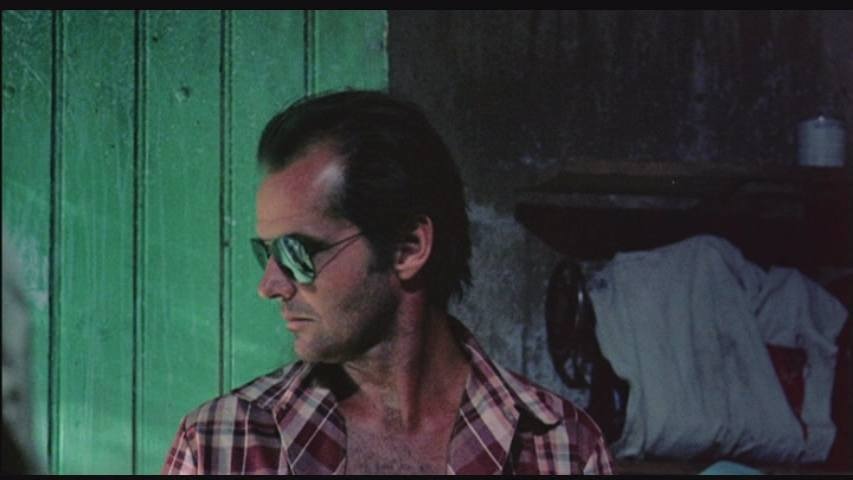

English-American journalist David Locke (Jack Nicholson) is wandering around Chad, looking for material for a documentary. After his jeep gets stuck in the desert he returns, exhausted and dehydrated, to his hotel. After cleaning up he knocks on the door of another room saying the name “Robertson”, but Robertson is unresponsive, lying face down on the bed. Locke is then shown at a table in his room, exchanging passport photos with Robertson, using a straight razor to peel them off. Locke assumes Robertson’s identity, little knowing that Robertson is an arms dealer selling guns to rebel groups in Chad. People back in England now believe Locke to be dead.

Back in England, wearing a mustache, he goes into his home after knocking, searching around. He picks up his obituary off a bed. He leaves and there is an endearing note from a lover on the door which annoys him. It seems his wife has been having an affair. He goes to an airport and in a locker discovers diagrams of guns in a zipup case.

Men are there it seems are watching him, but he leaves. He then goes to a church where the service is in German, being led to these places by Robertson’s appointment book. Someone is getting married. Afterward the men from the airport come and they exchange information about the guns for a cash instalment. They say they will see him in Barcelona, as had been previously arranged.

In Barcelona, now sans mustache, Locke finds that his old colleague Martin is on his trail. Both Martin and his wife are interested in finding “Robertson” to talk to him about Locke’s death. It turns out that Martin is staying at the same hotel as Locke, and he wants to avoid him.

Locke meets The Girl (Maria Schneider, remaining unnamed throughout the film) in a large house built by Gaudi for a corduroy manufacturer. They hit it off and he tells her frankly that he has changed his identity and is avoiding someone. He asks if she will get his things from the hotel for him and meet him afterwards.

What happens from here leads to one of the most fascinating endings of a film ever, with its famous seven minute tracking shot, seeming to convey visually the trajectory of Locke’s personal struggle over the course of the film. In order to achieve the shot, Antonioni had a camera on a track in front of a window’s bars.

The camera slowly moved toward the window, reached through the bars, and then was picked up by a crane outside, a system of gyroscopes fitted to the camera making the transition almost seamless. Soon after The Passenger was released, cameras were created in order to carry out such shots, but before this film, it had not been done before. As well as this unique achievement, the performances by Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider are truly great, as is the script, which is, above all, a fascinating exploration of identity.

Author Bio: S. D. Johnson is a poet and cinephile. Besides Antonioni, her favorite directors include Agnes Varda, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Andrey Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, Robert Bresson and many, many others.