3. The Birds (1962): The Bad Woman – The Good Woman – The Mysterious Woman – Mother – Guilt

Hitchcock’s next film, The Birds, was released, following the unanticipated success of Psycho, (a film that Paramount refused to finance, as they considered the source material too sordid), There will be more written here about this now iconic, but suffice to say that, when an initial investment of a mere $800,000 yielded ticket receipts that initially exceeded $40 million, it is clear that Psycho touched a nerve in American culture at the beginning of the 1960s.

For The Birds, Hitchcock returned to source material from Daphne Du Maurier, whose books, loosely adapted, were the basis the earlier Hitchcock films Rebecca and Jamaica Inn. Hitchcock also introduced Tippi Hedren in The Birds, an actress and model who had no experience in films, who had only appeared in advertisements and in bit parts in 1950s American sitcoms.

Hitchcock felt that Hedren could become the next Grace Kelly or even Vera Miles, who had disappointed Hitchcock by “having the audacity to get pregnant” and as a result could not play the role of Carlotta Valdes in Vertigo. Miles enraged Hitchcock, and in the discussion of Psycho later in this article, this will be explored further.

It is inarguable that Hitchcock’s best films, those most remembered and quoted, were made when he was in his mid-fifties to his early sixties. The list of those films are well-known: Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, North By Northwest, Vertigo, Psycho, The Birds.

However, during this period of intense creative output, Hitchcock was becoming more isolated, suffering from uncontrollable weight gain, heavy alcohol consumption, and garnering a reputation as a difficult director to work with who could make an actor’s life miserable on the set, even after work was completed. By this time, many of his female stars, even those who catapulted to stardom and who received Academy Awards (such as in the case of Joan Fontaine in Suspicion), were mistreated both on and off the set.

Hedren, an inexperienced attractive blonde, was the woman he had been waiting for: he could mold her, make her his personal creation, into a star who would create an historical impact in movies. Hedren, thrilled about the opportunity to work with the famous (and infamous) director, gratefully accepted a 7-year exclusive contract with Hitchcock that guaranteed her a weekly salary of $500.00 over the life of the contract.

The salary, even in 1961, was lean, a mere pittance, but was welcome to the novice Hedren, since it was guaranteed, unlike the on again-off again income that came with modeling and television work. The secure income would help to raise her daughter, the future actress Melanie Griffith.

Hedren was required to act in scenes that would have pushed even seasoned actors to their limit: in one memorable scene, she was brutally attacked by live birds for a full week, suffering a complete physical and emotional breakdown that resulted in the suspension of filming for almost a month on the orders of the company’s physician. This scene, when Melanie hears a noise in the attic, and foolishly investigates alone, is attacked by birds who swarm through a hole in the roof, mercilessly attacking.

The Birds is an allegorical film about the difficulty of finding intimacy in modern society; once two people, whether it be a man and a woman or neighbors, find common ground and decide to admit others into their lives, the new friendships and relationships are viciously prevented by life’s circumstances, and in The Birds, the resulting reward for trying, is death.

Most of the scenes were shot on location in placid and serene Bodega Bay, a tiny community outside San Francisco. In 1943’s Shadow of a Doubt, Santa Rosa, a is visited by Uncle Charlie juxtaposition of an otherwise placid town that is otherwise untroubled and secluded, the introduction of evil from outside, was seen earlier in Shadow of a Doubt.

Uncle Charlie’s arrival was heralded by the thick black steam spewing from the locomotive in which he was traveling to Santa Rosa. In The Birds, Bodega Bay was invaded by creatures who, like Uncle Charlie, were thought to be harmless and not suspected of posing any danger to the co-inhabitants of the community.

Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor), an attorney who commutes to San Francisco, frequently visits and stays in Bodega Bay with Lydia, his mother (Jessica Tandy) and his sister Cathy (Veronica Cartwright). While in the city, he meets Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) in a bird store, where she pretends to be an employee of the store, giving the opportunity to talk with Brenner.

Melanie’s ruse is discovered and, following personal attacks on her character regarding swimming naked in a fountain in Rome, then ending their conversation by telling Melanie, “See you in court,” Melanie inexplicably maintains an interest in this ostensibly cold man by purchasing lovebirds for his younger sister.

Deciding to deliver them personally to Cathy in the hope of surprising her, Melanie travels to Bodega Bay and, with the help of a middle aged store clerk (John McGovern) with whom Melanie flirts, she obtains a small motorboat and travels across the lake to the Brenner residence on the other side. While in the boat she is attacked by a bird, causing her scalp to bleed. Mitch sees this from his the house and rushes out to help Melanie and to dress her wound.

While staying with the Brenners she need Mitch’s mother, Lydia, a woman who maintains a hardened and wary facial expression upon meeting Melanie. In an example of incredible acting on the part of Tandy, when she is first introduced to Melanie, the camera lingers on her face as it manifests a series of expressions, starting with distaste, followed by rejection, then resignation.

This shot tells the audience that Lydia does not wish Melanie to stay longer than she needs to, and as we learn more about her through the film, we recall that the initial camera shot, which remained on her face a full ten seconds, was very telling, having informed us at the outset what would follow in the story.

Lydia is possessive of Mitch, what psychologists today would describe as “codependency” . One of the “symptoms” of codependency is the excessive reliance on someone for their own psychological well-being. The person afflicted relies heavily upon a person.

Lydia thus has extreme and excessive copendency with her son, Mitch which causes Mitch in return, to feel responsible for his mother’s psychological well-being. Because of this psychic burden, Mitch has little room for relationships with women outside of his mother; indeed, any new woman who has attempted to enter Mitch’s life has been made to feel unwanted by Lydia, and the pressure put upon these women is so intense that it negates any chance of intimacy Mitch may have wanted with them.

So, the only woman Mitch can be with, is his mother Lydia. With her he must be both a son, a husband, and a lover, to help soothe her anxieties, to coax he and to help her to feel happiness.

A very telling scene is after dinner. Lydia and Mitch are in the kitchen. While Mitch is drying the dishes, Lydia, in her soft-spoken yet firm speaking voice and manner, begin to interrogate Mitch about Melanie and his feelings for her.

Asking first how and where Mitch met Melanie, she pressures him further, as an attorney gifted in sarcasm might, regarding reports in the newspaper that told of Melanie’s exploits in Rome, and the fountain mentioned earlier here. Lydia’s remarks, such as, “Perhaps I’m old-fashioned….I know it was warm there (in Rome), Mitch, but…well…the newspaper said she was naked..”

Lydia’s needling makes Mitch defend his choice, and he tells Lydia that he can handle himself. The next part of the dialogue takes us from concerned mother to needy lover. But her codependent possessiveness and need are reinforced, wrongly by Mitch at the end of their conversation.

Lydia: Well…So long as you know what you want.

Mitch: I know exactly what I want.

The scene then dissolves, leaving the audience with quite an unsettling feeling. Whom does Mitch want? Is his choice Melanie, or is it Lydia?

This strange relationship is reinforced by Melaine’s conversation with Mitch’s former girlfriend, Annie Hayworth (Suzanne Pleshette). Pleshette’s acting role here as the jilted lover is brilliantly convincing. There is no room for her in Mitch’s life, because of Lydia. Her only choice, because she still has strong feelings for Mitch, was to move to Bodega Bay, just to be near him. Now that she is no longer a threat to Lydia, she and Lydia are now friends.

Lydia has again kept possession of her son/lover, and as the film continues it becomes clear that Mitch has chosen Melanie, the film takes a much darker tone as birds begin to attack, killing Annie first, then attacking the children at school, followed by the gas station, and finally Melanie herself.

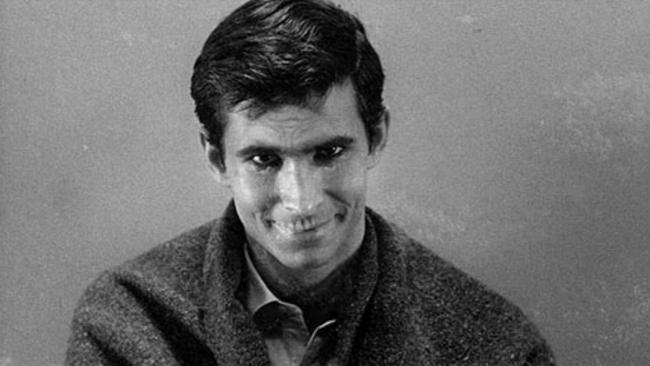

4. PSYCHO (1960): Catholic Guilt – Mother – The Bad Woman – Homosexuality

It becomes clear to any viewer and especially fans of Hitchcock’s films to note certain common themes and peculiarities in his 50 plus films and television program. Hitchcock was raised Roman Catholic, and anyone who attended Catholic elementary school, was exposed to a philosophy that at its core instilled the idea of original sin. Impressionable young minds were essentially told that they had already sinned, and their life’s work was to atone for having sinned.

We as human beings, it is told, are flawed, we are weak, susceptible to temptation, and easily led astray. Sex, but more especially the yielding to sexual temptation outside of marriage was immoral. Lust, even in the mind, is morally wrong, and would lead one down the road to perdition. Being caught in a “lewd act” was punished.

Desire, even attraction, was impure. Children in Catholic school were made to feel shame for having such natural feelings; the confessional was the place to confess these feelings, as well as bad deeds, to a priest. In Psycho, the punishment for such thoughts and the acting out of them in life, is murder.

Psycho, since it is such an excellent production on so many levels (conception, script, direction, music, photography and so on), can be interpreted many different ways. In this article, it has been concluded that Catholic guilt operates as the subtext for Psycho, and from this conclusion, Mother, Sam’s relationship with Marion, Arbogast, and Marion’s talk with Norman prior to her “purging her sins” in the shower can be viewed in a unique and hopefully accurate light.

The film, Psycho has a much darker and disturbing tone than the book of the same name by Robert Bloch upon which it is based. Bloch, who is Jewish, and was therefore not raised Catholic as Hitchcock was, injected his novel with humor that offset the intense subject matter and gore of the story.

This is not meant to say that there are not funny moments and lines of dialogue in the film that aren’t humorous (Hitchcock often stated in interviews that Psycho is a “funny” movie). However, it can be argued whether these moments of humor provide any relief to the darkly intense scenes of the movie. Some examples of humorous dialogue:

●Following the shower scene and Norman’s subsequent cleanup, the scene changes to Sam’s hardware store where a woman is reading the label on a can of insecticide. She states that she believes that “insect or man, death should be painless”; at the end of the scene, she says, “Well, if it isn’t painless, I just hope it’s quick!”

●Norman, having become aware that he will be visited again by Sam and Lila (and possibly the sheriff), picks up Mother to carry her to the cellar downstairs. The camera’s point of view is from the ceiling down to Norman carrying the body of his mother. Norman, speaking in a hushed tone, tells his Mother he is taking her to the cellar. She replies, “The fruit cellar? Do you think I’m fruity?”

●Cassidy and Lowery, the bank president, return to the bank. Cassidy is going to deposit $40,000 into the bank. On their way to Lowery’s office, Cassidy stops to talk to Marian. The desk occupied by Caroline (Patricia Hitchcock, the director’s daughter), is next to Marion’s. Yet Cassidy speaks and eventually propositions Marion. The audience is aware that Janet Leigh is attractive, more so (arguably) that Pat Hitchcock. After the two men go into Lowery’s office, Caroline says to Marion, “He was flirting with you! I guess he must have noticed my wedding ring.”

●Arbogast, the bank’s private investigator, stops by the Bates Motel to speak to Norman to ask him whether Marion had stopped at the motel and rented a room. He assures Norman that he is not a policeman. He asks Norman to look at a photo of Marion, but Norman is reluctant. Norman insists that Marion was not there, even though he has not seen the photo that Arbogast is holding. Arbogast says, “Mind looking at the picture before committing yourself?” Norman replies, “Committing myself? You sure do sound like a policeman.” (Norman had projected psychological instability earlier and in this scene).

Psycho is on one level, about meting out punishment for having done bad things, dispensing Catholic justice. We know, after having viewed the film, that Norman’s mother is dead, was deceased prior to the events that took place in the film, and that her perceived presence in the action of the film came from Norman’s disturbed mind.

So what did Norman’s mother represent to Norman in his mind? From the words that “Mother” spoke, she was repressive, objecting to Marion spending the night at the motel. (The name of the motel, “BATES”, can be interpreted as “BAITS”, a place, perhaps a church, that lures unsuspecting travelers there so Mother can once again mete out her punishment).

After Marion arrives, Norman “speaks” to mother and tells her that he is bringing a sandwich to Marion. Mother reacts violently, and and their conversation is overheard by Marion through the window in her room. Mother’s tone is one of condemnation:

MOTHER: I won’t have you bringing young girls in for supper! (A sneering tone is now heard in her voice). By candlelight I suppose, in the cheap erotic fashion of young men with cheap erotic minds!

NORMAN: Mother, please…(later) Mother, she’s just a stranger…

MOTHER: (mimicking cruelly) Mother, she’s just a stranger! As if men don’t desire strangers, as if…oh, I refuse to speak of disgusting things because they disgust me! You understand, boy! Go on, tell her she’ll not be appeasing her appetite with my food, or my son!…

NORMAN: Shut up! Shut up!

Viewing the characters in Psycho as symbolic representations, and considering what is the subtext of Psycho is, then Mother can be said to represent, or in Norman’s mind, actually is, a Catholic school nun.

In the scene that follows, Norman speaks to Marion candidly about his own lonely and monotonous life. Marion begins to confess to Norman about her own life and her troubles. Norman here can be said to represent a priest hearing Marion’s confession. She was in a hotel room, unmarried, with a divorced man. She was having sexual relations before marriage.

SAM: I’ve heard of married couples who deliberately spend occasional nights in cheap hotels. They say it –

MARION: (interrupting)

When you’re married you can do a lot of things deliberately.

SAM: You sure talk like a girl who’s been Married.

Religious, Catholic justice, has been served to Marion, Not because she stole $40,000, but because she has committed the sin of sex outside of marriage.

After Norman cleans up Marion’s hotel room, he performs a final inspection of the room, and finds the folded newspaper that contains the stolen money. He picks it up and indifferently tosses it into the trunk next to Marion’s body. Earlier, after the murder in the shower, the camera, in one long shot, moved out of the bathroom and into the bedroom, and comes to rest on the folded newspaper.

This sequence is yet another example of pure cinema, where the camera alone tells the story quietly and with neither music nor dialogue. Pure cinema occurs in North By Northwest, when Thornhill (Grant) is waiting for a bus in the cornfields, followed by the crop duster attack.

The elements of pure cinema, motion, visual composition and rhythm are utilized in Psycho when Marion arrives at the Bates Motel, and the camera films her room quietly while she is getting changed. We also see the folded newspaper which conceals the stack of cash.

Norman becomes conflicted when he looks through the peephole in his office at Marion undressing before taking a shower. The painting that hides the hole, called “Susanna and the Elders” is a depiction of two men raping a woman. After his conversation with his mother, the pangs of desire he feels for Marion are accompanied by feelings of guilt and shame.

The question is asked: Which part of Norman’s mind killed Marion, his own feelings of dread upon being aware of his lustful feelings, or his Nun/Mother side, who needs to punish Marion for her morally objectionable behavior? What is certain is that the film provides for its viewers a primer on Catholic philosophy of living a virtuous life. It forces the viewer to first identify with Marion, then upon her death, our sympathy is with Norman. When we realize at the end that Norman is Mother,

5. FRENZY (1972) – Food – Sex – Death

By 1972, Hitchcock’s main artistic output had come to an end. His circle of friends had diminished, his health was failing from uncontrolled obesity and unrestrained alcohol consumption. He hadn’t had a profitable film since 1964’s Marnie.

The events that took place during this, his past profitable film, were an embarrassment to him: his proposal to Tippi Hedren, her rejection and final (and perhaps well-deserved) disgust of him by this time, succeeded in isolating him from Hollywood and the entertainment industry. His next two films, Torn Curtain and Topaz were financial failures, and he made it obvious his displeasure with the actors that were chosen by the studio for each of these films.

In 1971, he returned to England to film Frenzy, a film that today deservedly ranks as one of his best effort. There is, for example, another case of transferring the trauma and violence to the mind of the viewer when the killer takes his next victim, Babs (Anna Massey) up to his apartment.

When Bob (Barry Foster) says to Babs as they ascend the stairs, “Did I ever tell you that…you’re my kind of woman?”, the camera slowly and silently descends the stairs just walked, in backwards motion out of the entrance doors and into the street. The viewer has to imagine the brutal scene that is happening at that very moment inside Bob’s apartment as the camera moves away. When the camera finally comes to rest across the street, we hear a bloodcurdling scream

Yet in closer study of this dark film reveals that it does not seem to have any redeeming message. Everyone is suspicious of each other, and there is a jarring juxtaposition of food and sex, as well as food and violence throughout the film. The murderer, Bob, works at Covent Garden Market as a buyer of produce, and offers the accused Richard Blaney (Jon Finch) grapes after he’s been fired from his job.

The lead detective for “The Necktie Murderer” case (Alex McGowan) is constantly being fed inedible food by his wife, who is experimenting with cooking. After Bob murders Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt) in the dating agency, he eats an apple he has taken off her desk. Blaney and Brenda, just prior to her being murdered by Bob, have an argument at a restaurant and during the meal, Blaney shatters a wine glass and cuts his fingers. Babs is hidden and taken out to be disposed of in a potato truck.

The murders seem meaningless, and have no motivation behind them as they did in previous Hitchcock films. The viewer never feels able to identify or to sympathize with any of the characters, so there is no feeling of loss when one of them is brutally murdered.

The protagonist, Richard Blaney, is an “anti-hero.” He has a violent temper, has threatened to kill his former employer, and spends most of the film as a bitter and vengeful character. We can only sympathize with him in the end because the actual murderer, Bob Rusk, is more reprehensible and disagreeable than is Blaney.

One of the most disturbing scenes in the film is the rape and murder of Brenda who runs a dating agency. Bob comes in while her secretary is away, and inquires as to why they have been unable to find a suitable dating partner for Bob. Brenda, with a look of thinly-veiled disgust, tells Bob that, based on his profile, no one would want to date him, nor would the agency want to set up a date for him, based on his “preferences.”

Bob gets angry, grabs Brenda and begins to molest her. The scene is long and drawn out, the comera focusing on her raised dress and legs, then her breasts, then finally, as we hear Brenda praying, the camera in a close-up fixes on her eyes as she is getting strangled with Bob’s necktie.

Having researched the director’s history with female actors, this scene is even more unsettling. The deaths of Babs and Brenda seem like a wish-fulfillment of sorts for Hitchcock who, having never had his own wishes fulfilled, exacts revenge against these women through Frenzy. Brenda’s death seems to take a near-lifetime. Film aficionados will appreciate the brilliant camera work of the rape scene, the cleverness of using the eyes of the victim to describe to action that is occurring.

The entire film, indeed, is extremely well-done. It is only wishd that there could be something redeeming in it. And there is one: Chief Inspector Oxford. Coming home to his delicate-featured wife, who uses him as a guinea pig for her culinary experiments, Oxford, not wishing to hurt his wife’s feelings, places the inedible food back into the pot when she is not looking, and seems to support her experiments. In irder to satisfy his appetite, he eats bacon and eggs at the police station, unbeknownst to his wife.

In addition, Inspector Oxford is the only person who believes Blaney is innocent, and with Blaney’s assistance, sets up a sting a Bob’s apartment which serves to vindicate Blaney. Inspector Oxford, of all the characters in the film, is the only one with any moral foundation, which results in a sense of order being re-established in a film that has no real moral message.

Author Bio: Joseph DeGregorio is a pianist, composer, freelance composer of music for TV and Radio. You can contact him at musiciwritr@gmail.com.

.