“The blind one. She’s the one that can see.”

–Laura Baxter (played by Julie Christie)

Death and the compass

An autumn garden in the English countryside, bucolic yet somehow unquiet, two children, Christine and Johnny Baxter (Sharon Williams and Nicholas Slater), gambol and play, unconsciously on the precipice of tragedy. Their parents, John and Laura (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie, both outstanding) are in parenthesis, a respite about to break and a trial about to be braved.

While looking at slides, comfortable in his country home, John has a suspicion, suddenly a glass of water breaks, and his premonition grays, he runs outside, knowing something is horribly wrong.

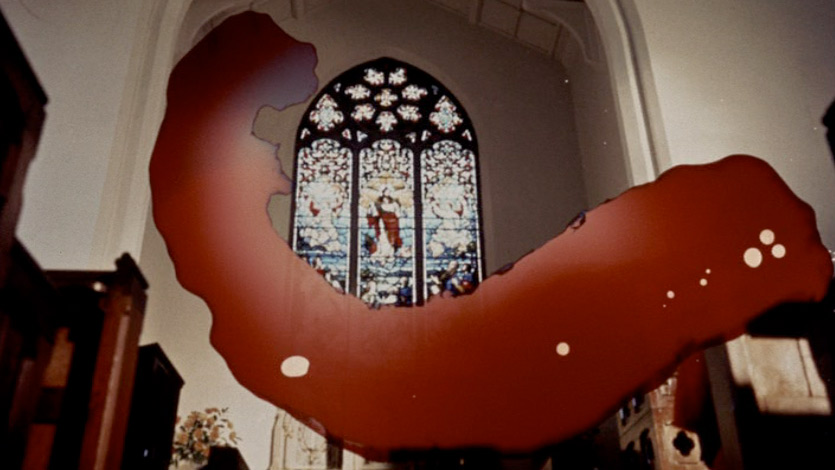

Prostrate, John arrives too late to the garden pond. Submerged, Christine, in a red coat that evokes Red Riding Hood, is bereft of life, has drowned. Aching, but in need of distance, John and Laura take a trip to Venice where John has accepted a commission restoring an ancient church.

“That beginning sequence is so strong that it colours the whole film. The couple, played by Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland, never escape from the grief. It crushes them and it crushes the viewer. It felt to me that there was something trapped in the film itself – something terrifying and deeply sad. It never really shows its face, but lurks in the edits, in the performances and casting. The film starts with a child falling into a pond and the ripples of this event move through the film… It’s an odd feeling, the realisation that you may have to revisit films at every stage of your life. I thought I’d ‘done’ Don’t Look Now. I had no idea. I suppose I should have had a clue, as it’s a Roeg film. It’s a kaleidoscope of meaning…”

–Ben Wheatley, director (Kill List, A Field in England)

Nicolas Roeg, born in 1928 in London, began his prolific film career as a cameraman. Early on Roeg was David Lean’s second-unit cinematographer for his masterpiece, Lawrence of Arabia, and other illustrious gigs, including cinematography for François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 in 1966, soon followed this high profile affair.

While Fahrenheit 451 remains one of Truffaut’s most underrated works it combined elements of horror and oppression which certainly would lend itself well to Roeg’s later works, as well as introducing him to Julie Christie, who would co-star in Don’t Look Now. But it was Roeg’s work in the early 1970s; his first films as director that would prompt his audacious and justifiably self-assured chef d’oeuvre Don’t Look Now.

One of Roeg’s signature stratagems for the film involves a narrative laxity, at once complex, intense and subtle, with a rein of movement analogous to his first two films as director, the visually forward Performance (1970) and the mesmeric Walkabout (1971), each with a teasingly askew chronology.

“[Don’t Look Now] remains one of the great horror masterpieces, working not with fright, which is easy, but with dread, grief and apprehension. Few films so successfully put us inside the mind of a man who is trying to reason his way free from mounting terror. Roeg and his editor, Graeme Clifford, cut from one unsettling image to another. The movie is fragmented in its visual style, accumulating images that add up to a final bloody moment of truth.”

–Roger Ebert

Once in Venice, John and Laura find themselves in a visually dense city of canals and daedal spaces. Water imagery is everywhere, a reminder to them and the audience of Laura’s death by drowning. Their sadness often overwhelms, the damp aqua pura of undoing and affliction.

Don’t Look Now is adapted from a novella by Cornish writer Daphne du Maurier, who is perhaps best known for writing novels and stories that later became masterpieces for Hitchcock; Jamaica Inn (1939), Rebecca (1940) and The Birds (1963). Du Maurier’s Don’t Look Now is a waterloo of timeless delicacy and crushingly observed qualities, a perfect match for Roeg’s sinewy strengths.

In the off season, as winter sets in, Venice feels half empty and idle, a doused city of ghosts. The perfect setting for a gothic ghost story, which Don’t Look Now certainly is. But it is also an occult thriller, and something entirely neoteric. Has there ever been a film like this before?

“I’ve seen her… and she wants you to know that she’s happy. She was laughing.”

–Heather (played by Hilary Mason)

With a tangled skein

Soon John and Laura meet two eccentric Scottish sisters, Heather and Wendy (Hilary Mason and Clelia Matania), one blind, who may possess the gift of second sight. She affably tells Laura she’s been in contact with her dead daughter. It’s too much for Laura to entertain, at first, but slowly it gives her a strange assurance.

When she presents this information to John he is beyond skeptical, but the atmosphere that Roeg establishes suggests otherwise. Abrupt cuts, unanticipated segues, ambiguous, often cryptic associations—the colour red, for instance—familiar from the beginning, here become more constant.

Multiple meanings, clandestine context, and stirrings of perpetual dread, and mystifying moments seem to slip along as if on water. John’s work in the archaic church involves a mosaic, one beset with antediluvian symbols, making surreal genuflections. Gestures that torment John and haunt the audience, we wonder along with him, what does it mean?

“Nicolas Roeg is a chillingly chic director; [Don’t Look Now] is an example of high-fashion gothic sensibility…Venice, the labyrinthine city of pleasure, with its crumbling, leering gargoyles, is obscurely, frighteningly sensual here, and an early sex sequence with Christie and Sutherland nude in bed, intercut with their post-coital mood as they dress to go out together, has an extraordinary erotic glitter. Dressing is splintered and sensualized, like fear and death… Roeg comes closer to getting Borges on the screen than those who have tried it directly…”

–Pauline Kael

One of the most tender and apocryphal episodes in the film is the decisive sex scene near the beginning the film. Courting much controversy at the time, this extraordinary scene, brazenly erotic, is also cryptic and equivocal.

Filmed with cunning and decorum, the sex act itself—the pre and post-coital passages, the empathy and excitement, why even the adornments and colour scheme of the hotel room—can be read into in a number of ways.

As part of the grieving process, as evidence of assent, as survival instinct, and as reception or refusal of love, whatever the intellection, this miraculously prolonged scene, be it shocking or sublime, or both, is lionized for a reason.

“To do a sequence like [the sex scene] takes it so close to the edge that people insist they actually see Laura (Christie) and John (Sutherland) making love – which they don’t because they didn’t – is all to do with trust. This was the fourth time Nic and I had worked with Julie Christie… so there was a lot of friendship and a lot of trust. We shot it one Saturday afternoon at the Bauer Grunwald hotel. The brilliance of that scene was in the cutting room. I didn’t know that Steven Soderbergh had homaged it in Out Of Sight, but that’s great.”

–Anthony Richmond, cinematographer for Don’t Look Now

Pino Donaggio’s luxuriant and suggestive score supplements the intrigue, in the same way that Bernard Hermann heated up Hitchcock. As Don’t Look Now advances, it coquets ever more with psychic and supernatural elements as Roeg reclines heavily on clues and motifs of an occult presence.

A periphery plot detail involves a serial killer at large in Venice, and, given the syllabus of the story; death, intrigue, eroticism, and Italy, this pegs the film, to an extent, as a giallo picture, albeit illusively. Horror is certainly on deck, but it is much more intangible, like a ghost.

The grief and the cycle of heartbreak, nostalgia, and reproach offer the real unruly alarms here. It’s a deeply felt brain wave in all respects of the film, and that is part of what bumps it into the upper echelon of British film.

As well the pairing of Christie and Sutherland is superb, on a recent viewing of the film, and maybe I need to dig further to explain why exactly, but their star quality and connected grace called to mind William Powell and Myrna Loy, best remembered as Nick and Nora Charles in the Thin Man films. Maybe it’s just the mystery angle and evocatory nature of their surroundings that inspired the correlation, as their leitmotif and spirit bend just about every place else.

“Don’t Look Now is the greatest husband and wife film there has ever been. What’s really remarkable is its explicit depiction, sexually and emotionally, of a long-term adult relationship. It is usually classed as a horror film, but the director Nicolas Roeg doesn’t work with fright in the easy, jumpy sense of the word, like The Exorcist, which also came out in 1973. It is Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie’s relaxed performances as John and Laura Baxter, a couple mourning the loss of their young daughter, that make the film shocking; Roeg works with deeper emotions like dread, grief and apprehension and that is how the horror accumulates.”

–Danny Boyle, director (Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire)

A study in scarlet

As earlier expressed, the colour red, first flashed in Christine’s unsettling coat, also an inference to the ultimate babe in the woods, Little Red Riding Hood, is one of Don’t Look Now’s most enduring and celebrated pieces of iconography. The very suggestion that Christine is lost in the forest, metaphorically speaking, is part of the perplexity.

At various times throughout the film the red coat reappears, often in fata morgana artifice, half-glimpsed by John and by the audience or subtly like Laura’s boots or handbag. In a reflection on the watercourse, like a mirage or a fantasy, or as a cry of wolf, the blush of red also bleeds into another constant of the film, that of the doppelgänger.

Without getting too divulgent, the idea of doubles makes an adverse ubiquity in the film, as a means of mistaken identities, police sketches, aberrant photographs, and more. Nothing is what it seems is a tenet of the film, absolutely.

As John discovers his Venetian distraction, a rouge-smattered hall of mirrors, it may also be a city that is bloodless, all its inhabitants are apparitions. As the story wanes, a final surprise jolt impairs us, one that’s part menacing, part left of field and full of bite.

Don’t Look Now glares fixedly at a husband and wife, their detached grip on life, the knots of their espousal, the intricacies of love, the morass of monumental loss, and what it casts a candle to is troubling and shaky but dazzling all the same.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.