“The most exciting use of cinema I’ve seen.”

– Tennessee Williams

Look Back in Anger

Is there a filmmaker alive today that’s as notorious, unflinching, and otherworldly as octogenarian and old hand, Kenneth Anger? Arriving from the postwar America experimental film movement as a sort of answer, at least initially, to Buñuel and the surrealists, Anger’s artifice and ability was, and remains, a deft Left-Hand.

Incited tirelessly by his polymath imagination, his insights into the occult, and a visually ravishing peculiarity, pinched, as it were, from an uncommonly diverse and deep well of influence and antecedents – Aleister Crowley, Coleridge, Man Ray, Méliès, classical Hollywood, pop music – to fashion an out-and-out infernal cosmology like no other.

Born in 1927 to an old-line bourgeois Santa Monica family, at the dying end of the silent cinema era, Anger was initially a child actor. As an eight-year-old Anger claims to have starred as the Changeling in William Dieterle’s and Max Reinhardt’s 1935 version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (though there is much dispute over this claim, often believed to be a publicity ploy on Anger’s part).

But, from an early age, Anger’s avant-garde angle was distinctly discernable, even decades before his egregious, at times unforgivable, gossip treatise, Hollywood Babylon and its sequels, would top best-seller lists in 1965 and forever after that.

Anger was always hell-bent on controversy and iconoclasm, but never more so in his hypnotic, forcible films, each overflowing in wonderful and dangerous ways; audacious superimpositions, mind-blowing bursts of colour, shocking homoerotic representations decades ahead of its time, cutting-edge and often ironical use of music, and meticulous framing that has ensured his work be shown in museums and art galleries the world over in perpetuum. Is it any wonder that modern formalists as diverse as David Lynch, Martin Scorsese, and John Waters, hail him as a virtuoso, and as a black magician of motion pictures?

I Put a Spell on You

A delirious and dynamite amalgamation of star quality and sorcery supplies the heart of Anger’s nine-part Magick Lantern Cycle (1947-81). Literal sorcery, too, I might add, Anger being a longtime practitioner of Thelema (the freethinking and thereby immoral religion developed by the aforementioned English occultist, Aleister Crowley), a belief system inundated with archetypal imagery, curious and erratic symbolism, and ideas as well as practices that have enraged and unscrewed the uptight and God-fearing from the get go.

The Cycle is as ambitious as it is ecstatic and while some of the films are more complex and phrenic than others, all contain a rich, rewarding aberration, as well as the mark of a singular, crushing talent.

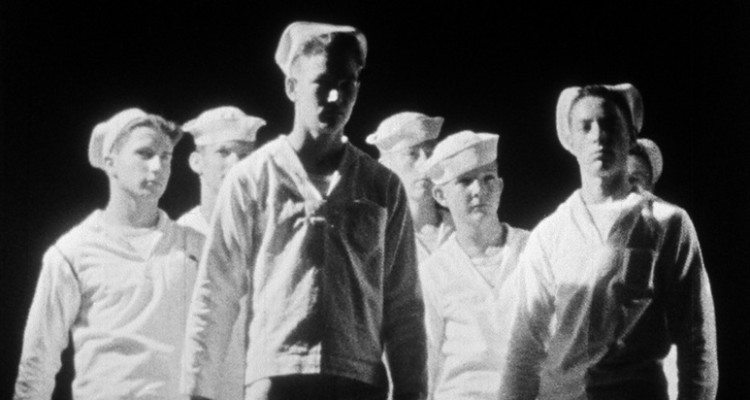

The first film proper in the Cycle is 1947’s homoerotic sado-masochistic songlike experiment, Fireworks. Filmed in 35mm black and white over a long weekend by a teenaged Anger, in his parents’ Beverly Hills home. More mischievous than Machiavellian, Fireworks follows a young man, the Dreamer (played by Anger) as he dresses amidst a surreal swirl of macabre and ultra-masculine macho images.

Shirtless teenaged boys flex and strut, peacocking for the camera amidst savage violent similitude recalling the then recent Zoot Suit riots (Anglo American serviceman, marines and sailors mostly, clashed with Latino youths in a series of violent skirmishes in L.A. in 1943) as well as the stream of consciousness films of noted female experimenter Maya Deren.

Seeing the fair and youthful Anger, lusting after other males, milk suggestively splashing his face, or the cheeky but outright rash Roman Candle alight and protruding from his crotch all amount to some great gags, though perhaps too verbatim, didn’t tickle everyone’s fancy, unfortunately.

Following its release Anger was arrested on obscenity charges and then, just over a decade later, in 1958, theatre manager Raymond Rohauer of the Coronet Theatre in L.A. had a lawsuit brought against him for screening the film. The case became a long fought obscenity trial in the California Supreme Court, which eventually ended with Fireworks rightfully being declared a work of art.

Puce Moment (1949) is Anger’s loving laudation to silent-era whimsy wherein he collaborated with another Angelino firebrand filmmaker and New Queer Cinema forerunner, Curtis Harrington (Night Tide, Queen of Blood), his cameraman on this occasion.

Shooting in colour and using a twinkling, glowing rhinestone and purple puce gown, Yvonne Marquis, long-lashed, and flapper fashioned (also the obvious template for Isabella Rossellini’s character in David Lynch’s bawdy Blue Velvet), seated on a chaise longue preens around to psychedelic folk-rock, easily anticipating the modern music video.

Anger’s grandmother, Bertha, was a seamstress and a costume designer for the silent era, Marquis’ dress in Puce Moment was from her collection, making it authentic, and the house it was filmed in belonged to Arthur Jasmine (also known as Samson De Brier), a star from numerous silent pictures.

“Some movies can be the equivalent of mantras. They cause you to lose track of time you become disoriented magical things can happen. Magic causes changes to occur in the universe. You can mix two elements together and get an unexpected result just beyond the edge of what you realize.”

– Kenneth Anger

A Stately Pleasure Dome Decree

1950 saw Anger appropriate a Parisian soundstage for his blue-filtered Méliès manifestation, Rabbit’s Moon. Existing, as it eventually would, in two distinct forms (a 16 minute version, and later, in 1979, a punchier 7 minute variant), Rabbit’s Moon remains a gripping and elegant showpiece set amongst a wooded glade—consisting of meticulously hand-painted leaves—during a full moon.

A clown, Pierrot (André Soubeyran), is pining for the moon, where, as detailed in Aztec and Chinese myth, a rabbit lives. Pierrot and his fruitless attempts to reach the rabbit in the moon, draws the attention of another archetypal clown, Harlequin (Claude Revenant), who teases and torments him, ultimately introducing him to Columbina (Nadine Valence), with whom Pierrot canonizes completely.

Both versions of the film marry hypnogogic imagery (Marcel Carné’s peerless pièce de résistance Les Enfants du Paradis is the obvious reference) to popular music. The original version, though filmed in 1950 wasn’t assembled and edited until 1972 when Anger also fashioned a soundtrack overfull with 50s and 60s pop by doo-wop groups the Capris, the El Dorados, and the Flamingoes, R&B act the Dells, and Motown mainstay Mary Wells.

This juxtaposition of mythic imagery and eerie doo-wop makes for a devilish and deeply effective mixture. At once out of place (pagan symbolism dancing to love song saccharine) and perfectly paired for a phantasmagoric reflex of top-flight fancy. The shorter version of Rabbit’s Moon, from 1979, points up a loop from the obscure Britpop band A Raincoat called “It Came in the Night” that is, without a doubt, a piece of pure pop paradise.

The Commedia dell’Arte demonstrated in both renderings make for a remunerative and epic mini masterpiece that seems to only improve and enhance over the years. Perhaps more than any of his other works, Rabbit’s Moon feels the most modern and yet paradoxically archaic short, perhaps owing to the tricksters who inhabit it.

Inspired by the Villa d’Este fountains in Tivoli while accompanying avant-garde experimental film matriarch Marie Menken, Anger’s Eaux d’Artifice (1953) makes the most out of slow-motion shots of such gushing revelation. Was Vivaldi’s “Winter” from The Four Seasons ever used to such Daliesque kitsch? The foam imbued geyser, phallic champagne bottles bursting sexual sputum is both sexy and snappy, recalling the lucid eroticism in Buñuel and Dalí’s surreal comedy L’Age d’Or (1930).