“Those who dismiss Woody Allen as a neurotic narcissist out of touch with reality need to confront 1983’s Zelig. Perhaps the most complex, unusual film in an already diverse CV, it remains his most culturally and politically aware work, its relevance increasing with each passing year.”

– Tom Huddleston, Time Out

I’m sitting on top of the world

Through dumb luck and a little deceit I wound up with a year-long pass for a now decamped repertoire cinema just before I began film school in 1997. There was a month long Woody Allen retrospective showing at this time and I was in utter elation.

I’d never seen Annie Hall (1977) or Manhattan (1979) projected on the big screen with an appreciative audience hanging on every utterance, laughing in all the right places, with lively discussion and fast friendships forming in the lobby, spilling out into the mild and obliging Spring evening afterwards.

Even better, there were several of his films I’d yet to see at that time, such as Broadway Danny Rose (1984), Stardust Memories (1980), and Zelig, all walking distance from my basement apartment, and all for free. I had a thing for black-and-white film at the time –– still do, truthfully –– so that had me intrigued, not to mention how Allen and Gordon Willis’ collaboration on the aforementioned Manhattan was a discernible miracle.

I’d been on Allen kicks before, had devoured his books “Without Feathers” and “Side Effects” and had written my own embarrassing screenplay which borrowed so heavily from Annie Hall I’m even now still ashamed to show even a sentence of it to anyone. But I digress.

“Not everybody has the staying power, not everybody has the tenacity, and not everybody has so much to say about life, continually,” said Martin Scorsese in a PBS interview regarding Allen, also, of course, a fellow New York filmmaker.

And this generative artist is certainly the Allen I always think of, especially recently as his 47th film as writer/director, Café Society (2016), enjoys a wide release and excellent notices.

Not only is it amazing that Allen can be so prolific, but consistent and relevant as well. Recent works like Blue Jasmine (2013), Midnight in Paris (2011) or Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) can corroborate this point quite clearly. Even his lesser enterprises like Whatever Works (2009) or Irrational Man (2015) hold more value than most of what you’ll find at multiplexes at any given time, truly.

And so it was that I found myself, in 1997, sitting in the Ridge Theatre on Arbutus Street in Vancouver about to view Zelig (1983) with very little prediction beyond a few zingers and some sunny complications. Zelig hit me like a timid, bespectacled torpedo.

“Though it runs a mere but delicious 84 minutes, Zelig, [Woody Allen’s] new, remarkably self-assured comedy, is to his career what the 15 1/2-hour Berlin Alexanderplatz is to Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s and the three-hour-plus Fanny and Alexander is to Ingmar Bergman’s.”

– Vincent Canby, The New York Times

Doin’ the chameleon

A slender and spry film — it’s over in less than an hour and a half — an economic running time that so few overlong films of today seem incapable of aping, Allen’s Zelig doesn’t scramble nor does it frazzle in its largely anecdotal and episodic machination.

A mockumentary (Allen had played with the genre before in 1969’s Take the Money and Run), it crested the wave of analogous comedic misadventures in a genre that has now become a cinematic staple in movie houses everywhere, and predates Rob Reiner’s side-splitting This is Spinal Tap by a solid year.

Narrator (on Leonard Zelig’s rough childhood): “Bullied by anti-Semites, his parents … side with the anti-Semites. They punish him often by locking him in a dark closet. When they are really angry, they get into the closet with him.”

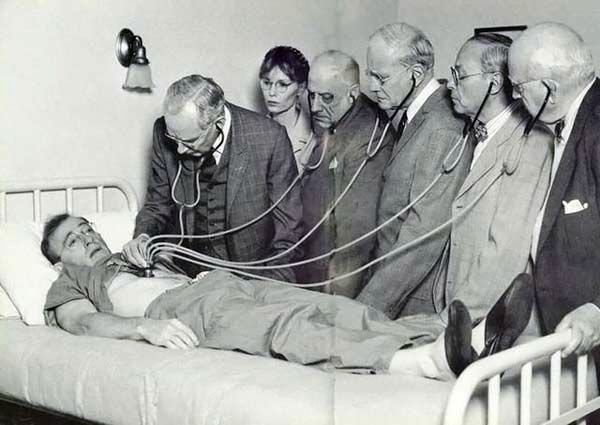

Linking authentic and spoof newsreel footage, poker-faced modern-day talking-head interviews (including Saul Bellow, Irving Howe, and Susan Sontag) and special effects that not only hold up amiably, are hard to distinguish from the actual footage it’s seamlessly merged with, all to service the story of one Leonard Zelig.

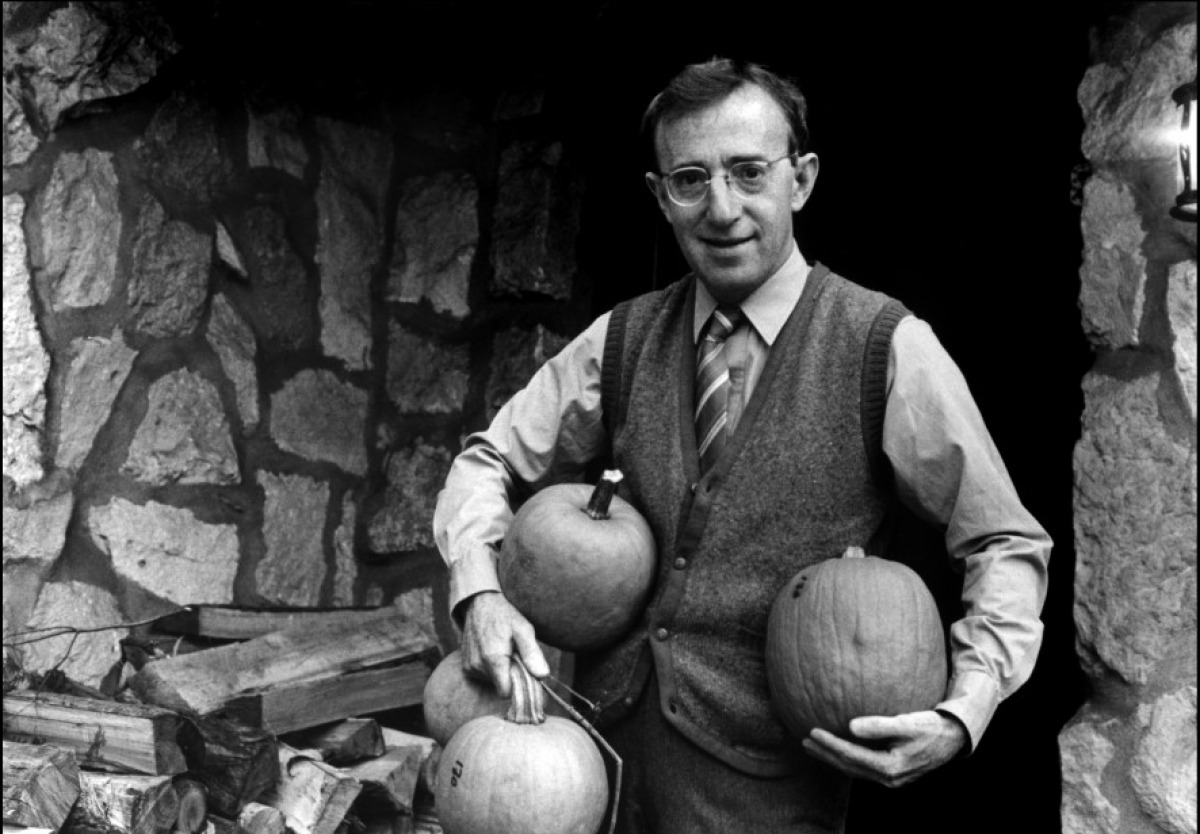

Leonard (played pleasingly by Allen), when we first meet him, is a 1920s Jewish gentleman with a perplexing “chameleon disorder” which permits him to parallel, often strongly resembling, anyone whose company he shares.

Dr. Eudora Fletcher (Mia Farrow, superb) is the sympathetic and somehow woebegone psychiatrist who not only aids him, but the pair fall in love, too. As Leonard becomes a sought-after celebrity-phenomenon he parties with F. Scott Fitzgerald, hobnobs with Clara Bow, Charlie Chaplin, Carole Lombard, and Josephine Baker, amongst others, before inspiring a hilarious flapper-approved dance craze.

His crazy trajectory has him fall in and out of favour with the hoi polloi, pulling a Lindberghian aeroplane antic that defies the Nazis (yes, he even has a showdown, of sorts, with der Führer) all while doing the whole idiot-savant-amongst-historical-figures schtick a decade before Forrest Gump (1994) tricked you into thinking he was being innovative.

You may be six people, but I love you

Picaresque with its pearl-on-a-string stencilling, Zelig certainly seems to reiterate and possibly stem from Allen’s early days as a stand-up comic.

It is a film that’s heartily and freely fragmented, and overrun with formal challenges that lend it, to my mind, magical properties (properties shared by several of his films from that era, namely 1985’s The Purple Rose of Cairo and 1987’s Radio Days). Collage-like and eccentric, the entire film is a virtuoso piece from its very first frame.

“Zelig is both a writer’s and a director’s film, a movie that could not have been made if Mr. Allen hadn’t served time as a stand-up comedian and as a ferocious student of films, as well as the kind of writer who is so comfortable at the typewriter that he doesn’t hesitate to write ‘on speculation.’ One of the more invigorating aspects of Zelig is its technical wizardry by which new black-and-white footage and new soundtracks are seamlessly blended with a lot of material dating from the 1920’s and 1930’s.”

– Vincent Canby, The New York Times

Much can be made out of what Leonard Zelig represents, from anonymous everyman to assimilated Jew, he tries desperately to fit in. Melting-pot America one moment, lovelorn loser the next, Zelig and its eponymous character fittingly seem to alter over the years with subsequent viewings. As mass capitalist, petite bourgeoisie poster boy, hero, villain, dissident and conformist. Leonard truly triumphs and wins Dr. Fletcher’s affections anew when he defers to ordinary workaday life.

While Allen has paid lovely and vigilant tribute to the jazz age with Sweet and Lowdown (1999) Midnight in Paris (2011), and Café Society rather recently, neither of these really match the genius and the design of Zelig, one of the seminal works of a sincere master.

And while it may be Annie Hall that is the sentimental favorite in Allen’s colossal collected works, Zelig, like when I first saw it unsuspecting in the delighted, darkened bijou years ago, is a correspondingly ingenious and nostalgic sleight of hand.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.