In the hands of the masters, no form of dramatic expression is more powerful than comedy. The cliché that all comedy is born of tragedy is no exaggeration. Laughter is the strongest defense against what can often seem a terribly cruel and unjust world. At its best, humor laughs at the same moment it commiserates with its audience. And this is a pretty tough needle to thread, tantamount to successfully telling a joke at a funeral.

Literary greats achieve this with deadly precision, such as Jean-Paul Sartre’s achievement in the painfully familiar No Exit. Modern comics such as Amy Schumer use satire for highly vulnerable looks at treacherous issues like misogyny (her self-deprecating parody of 12 Angry Men comes to mind).

In the world of cinema, there have been a handful of giants who best used the medium’s visual language to convey the mechanisms comedy provides in response to the very stressful world we all must live in.

Some of those giants carefully crafted alter egos on film to act as human emissaries to the audience. The two most well-known and obvious examples of this would be Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp and Buster Keaton’s Stone Face. But probably the most sublime and transcendent of all would be Jacques Tati and his character of Monsieur Hulot.

Throughout Chaplin’s prodigious output, the most common theme his comedy explores is very straightforward: gaming an unjust system through sheer rascality. Using his acrobatic prowess as physical expression, he literally weasels his way in and out of every sort of unconscionable affront to the auteur’s sense of inequity.

The famous chase sequence in The Kid is emblematic, where the Tramp squirms, falls and leaps his way to literally beat back authority from separating himself and his beloved orphan child.

Keaton explored a different sort of motif. The Stone Face character makes his living sidestepping the dangers of the natural and human constructs he is compelled to confront.

Playing more to a stuntman’s sensibilities, Keaton’s signature moment is in Steamboat Bill, Jr. When a cyclone blows a huge wall down on him, he’s spared by virtue of standing right where an open window drops, missing being crushed by inches. These sorts of disastrous orchestrations play right into Keaton’s running gag of humanity’s helplessness in the face of fate, always a thin thread away from tragedy.

The Tramp and Stone Face’s struggles are highly kinetic, explosive confrontations with unabashedly malignant forces – even the natural world can play the antagonist. Here is where Tati, the disciple of both Keaton and Chaplin, evolves from his spiritual progenitors’ milieu and takes a more nuanced, quiet and ultimately profound comedic path.

Monsieur Hulot is neither acrobat nor stuntman. He doesn’t have or need the Tramp’s pugnacious brazenness nor the Stone Face’s devil-may-care navigation of his world. Trained as a mime, Tati’s recurring character is more bemused, restrained and clumsily maneuvering as he reckons with human constructs.

From social mores to disruptive architecture, M. Hulot finds himself constantly misplaced in the functions of an ever-more encroaching modernity. Bereft of immediate existential threats, Tati doesn’t require the superhero-like response of Keaton and Chaplin. Indeed, Tati has no real adversaries to contend against.

Any confoundment or obstacle thrown in his way isn’t an enemy to overcome with strength and guile, but an unhappy accident that will eventually find resolution with happy accidents – which are also extremely hilarious.

It’s this laid back “everything will eventually sort of work out” attitude which makes Hulot’s oeuvre stand out. He seeks laughter not in the dregs of consequential urgency, but in the daily grind of getting through a world that is so ridiculously and needlessly complicated, the audience can’t help but realize they are laughing at they themselves.

This isn’t a mean thing. Tati’s great empathy and even optimism exudes in Hulot’s outings, transcending them as the character himself fades more and more into the background with each subsequent film. He’s reaching the “everyday us” rather than the “notable other” which denote the unforgettable exploits of the Tramp and Stone Face. And ultimately, he offers an everyday hope as well.

While M. Hulot made several appearances, the character’s three major works are indisputably Les Vacanses de Monsieur Hulot (Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday), Mon Oncle (My Uncle) and Playtime. It’s in these films which Tati most effectively conducts his themes through the bumbler’s eyes. From the beginning, we see Hulot trapped in a world he never made. He is an organic being forced to interact in the inorganic world of modernized society.

This is the Hulot dilemma. From dealing with inorganic social constructs (Les Vacanses), to balancing the twin disruptions of interpersonal and industrial maturation (Mon Oncle), leading to the apparent final triumph of an imposing abstract physicality into every aspect of environmental interaction (Playtime).

Examination of the core Hulot works reveals the progression in how Tati explores his themes. His use of filmic visual language, along with Hulot’s physical clashes with bewildering manufactured environments, yields a unique treasure trove of comedic subtleties. And because the laughs come from such a familiar place, quiet recognition quickly blooms into uproarious self-ridicule.

Again, it’s not a mean thing coming from Tati. He knows as well as we do how little control we have over our encroaching technological growth. If anything, the director is letting us all off the hook. It’s simply not a natural world we’re confronting anymore, and the pace of change mesmerizes everyone.

Instead of bemoaning a lost era, or disdaining the agents of change, Hulot helps us lovingly laugh at our own shortcomings, while simultaneously celebrating our ability to ultimately overcome the tangled web we weave for ourselves.

Appropriately enough, Hulot’s introduction to society comes in the fantastically silly Les Vacanses de Monsieur Hulot. Before Tati took his alter ego into a full confrontation against modernity itself, a summer holiday spot provided the perfect setting for our beloved maladroit to stumble into modern social mores.

From the outset, we see how Hulot is visually shown as being behind the times. Driving his rickety old jalopy to a popular beach spot, our hero is quickly outpaced and left in the dust by a new-model vehicle. Overpacked trains and busses cram piles of fellow travelers toward the relaxing destination, creating extra stress on the way to their supposed relaxation. But Hulot feels no such stress. His car is such a decrepit throwback, it might almost just as well be a donkey.

A slower, almost pastoral approach to life makes him incredibly mellow about dealing with all of its inconveniences. Which, of course, continuously irritates the uptight crowd he shares his vacation with.

Early on, a scene in the small boutique hotel’s sitting room sets the stage for the casual disruptions Hulot unwittingly generates. All the prim and proper guests are sitting very stiffly and quietly. They read newspapers, play quiet games, sleep, whisper, and otherwise create a chilly silence in what is supposed to be a fun beachside resort.

Hulot’s first appearance happens during a very windy moment. He opens the door, lets the gusts flow in, absentmindedly turns away his attention, thereby allowing a mini-gale to bellow through the stagnant setting. Papers fly, hats soar, and moustaches flail like scarecrow arms. Naturally, everybody gets pissed off at Hulot. But he can only be confused.

There was no malice in his action. He probably doesn’t even understand what he just did. This is a guy who’s just moving at a different speed, still pausing long enough to uncover a world chock full of wonder.

Foiling his orderly and rigid hotel-mates isn’t a job, it’s a consequence of his adventure. These aren’t just miraculously choreographed sight gags. Tati isn’t a rapid-fire laugh factory. His slow-cooked approach envelops the entire atmosphere of scenes, filling the air with the scent of the comedy moments before serving up the main course of chaotic confusion.

And so it goes throughout our hero’s holiday. At one moment, he’s blasting a record in the music room, only to have a mob of angry fellow patrons pull the plug on his annoying jam session. One of the film’s more famous moments has Hulot’s damaged kayak splitting into a shape resembling a giant shark’s mouth – sending all the swimmers running for the beach.

There’s even a grim moment when car trouble has him almost smashing into a funeral, only to have his flat tire covered in sticky leaves mistaken for a sympathy wreath. The sharpest statement, however comes in a tennis game. Having been taught erroneously how to handle his racket, Hulot takes to a court with a most unorthodox and hilarious-looking serve.

Amazingly, this ludicrous technique proves to easily overcome all of the smug, well-dressed folks who fancy themselves sophisticated players. One after another, they fall to Tati’s clever expression of the organic being at play, lacking the confidence of structure, as well as the fear of losing. This all wins at least one adult fan in Hulot – the tennis umpire who simply delights in how he aces all of those hoity-toity jerks.

And of course, he has child fans try to emulate his style in a ping-pong scene later in the film. It’s not an accident most of the people Hulot can seem to relate to in the film are children. He has trouble navigating most of the constructs of adulthood exactly because his sense of wonder remains stronger than his need to conform.

Again, it’s not that Hulot has any score to settle. Revenge isn’t his gig and neither is justice. He just is who he is and the neurotic world of fast-paced modernity is just as confused by him as he is by it. One way to think of this character’s journey is like following a drop of rain streaking down a wall. If the wall is sleek and flat like aluminum siding, the raindrop will whisk straight down, maybe faster than you can follow it.

Hulot’s raindrop path is more like what you’ll find with an old wooden barn. Irregular cracks, warped folds and sudden splinters take the gentle water on a more meandering journey. A child’s eye can trace its movements with the joy of surprise as courses suddenly change, speeding up and slowing down, concluding in a more memorable itinerary.

This is how Hulot flows. He can’t do the flat surface of modern life. He’ll always find the cracks in the perfectly planned landscapes he encounters. Following his journey etches a different kind of memory in our minds.

Hulot’s next adventure gets a little more physical – and Tati’s style becomes quite a bit more cinematic. In Mon Oncle, there’s not just stiff people to content with, but a stiff, modernized physical infrastructure. Somewhat a middle-of-the-road marker for the multi-film arc, Mon Oncle places Hulot on the cusp of the “old world” of a simple pre-war existence, and the “new world” of postmodernist architecture and sterile industry. The dichotomy is stark.

On the one hand is Hulot’s safe place: a quaint village of winding cobblestone streets, familiar ne’er-do-well characters loitering about in coffee houses, and even rag men in horse-drawn wagons. Pushing right up against that is his sister and brother-in-law’s lifestyle: a steel hard-angled ultramodern home that exudes sterility where insanely vapid and superficial garden parties are thrown.

Add to that the home’s cheerless interior, overwhelmed with ostentatious and needlessly complex modern appliances for the housewife to play with (and show off with). And the husband even works in a morose yet spotless plastics factory – what more visual symbolism of empty existence does one need?

And right at the heart of the film is the Hulot character’s nephew. It is with this child who Hulot most relates to. And Hulot is the only adult the boy ever looks forward to seeing. In between watching the family’s devotion to a hollow world of automation and finishing school social niceties, we get to follow Hulot in and out of his natural environment, often taking his nephew in tow.

Here perhaps is the space which is most emblematic of the film. The boy is always being pushed by his parents to be orderly and responsible. But at the same time, of course, he really needs to be a kid. Along with this, Tati recognizes his alter-ego should kind of grow up a little. It’s the very same adults in the film pressuring him to get a job and get serious about a career.

Therefore, a visual motif for the conflict is born: cold, precise metallic geometrics vs. a warm, breathing, earth-toned community. Mon Oncle has definitively announced that the series has moved into color, and the director’s use of palate could not be more pronounced. But when it’s Hulot and the kid hanging out, the two environments blend and overlap. This is a place where huge vacant lots act as back roads, complete with street vendors, and kids play in the dirt while pulling pranks on grownups.

Yet the borders of the two worlds are never far apart. A newly paved road can be found alongside a crumbling brick wall, overgrown with vines. It doesn’t feel like a clash anymore. There’s a sort of visual acceptance of the two supposedly opposing worlds. Even stray dogs in the film seamlessly chase each other in and out of the dual settings.

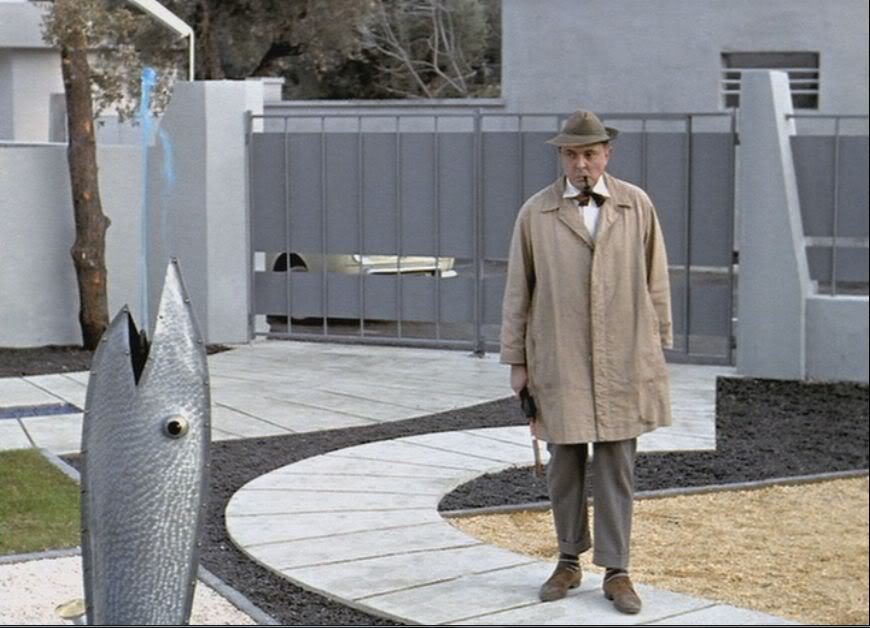

Bringing us here is an updated and more refined character in Hulot. His trademark walk is now always prevalent. Costuming has become icon as now his trench coat, pipe, umbrella and high-pants strike a personal stamp. Watching him bike around town meeting friends in his little atavistic district is terribly charming.

A famous scene has him walking to his third story apartment in the boarding house he lives in. It’s an up-down, left-right anarchy the audience tracks through glimpses of Hulot’s head and feet peeping out of windows and balconies. We’re treated to appearance after appearance of a street sweeper who’s always on the verge of dispatching a pile of rubbish, but never quite gets to it.

Everybody knows each other. Hulot’s bottomless affability is warmly welcomed all over town. The lovely young girl (a fellow tenant) who greets him every morning encapsulates the child-like quality which these more laid-back folks are only too happy to embrace. Conversely, this organic creature finds a less nurturing environment back in adult-world.

Mon Oncle’s many scenes where Hulot dives into the depths of modernity are unforgettable comic calamities. Fiddling around with his sister’s ridiculous kitchen gadgets leads to slapstick moments of perplexity. Her ridiculously convoluted and insipid lawn forces Tati’s character to inspire clumsy new maneuvers to get around the yard.

Mild negligence at his plastics factory job – which his brother pressed him to take – results in an anarchy of meter after meter of unsorted tubes to spill about the complex like so many loose guts. Beyond the laughs, the motif of the organic/inorganic conflict is always present. Upon closer inspection, though, a sub-motif begins to appear.

Over the course of the film, Tati makes sure to show us the organic not only in contrast to the inorganic, but even living within the inorganic. Successive viewings of the soulless postmodern home reveals it has a face, a hand, searching eyes, and even a penis, complete with bursts of urination (which oddly only occur when these urban gentiles are trying to impress their society friends).

It’s a hilarious discovery to make once the viewer finally gets it, but it also helps evolve a more powerful message – one Hulot would have but one more opportunity to make in the subsequent Playtime. As our hero gives us his adieu for the film, organic changes are abound. The young girl he greets every day has become a woman, a process he seemed unaware was happening. Hulot himself is sent off to a bigger city to take a bigger job and finally “grow up.”

As for his nephew, there’s a sense that he will conform to a more adult persona. On the flip side, at that same moment, Hulot’s stiff brother-in-law suddenly exposes a more gleeful and playful side to the young boy. It’s not just that the “immature” must “mature” but also to recognize that the inorganic is, at heart, organic.

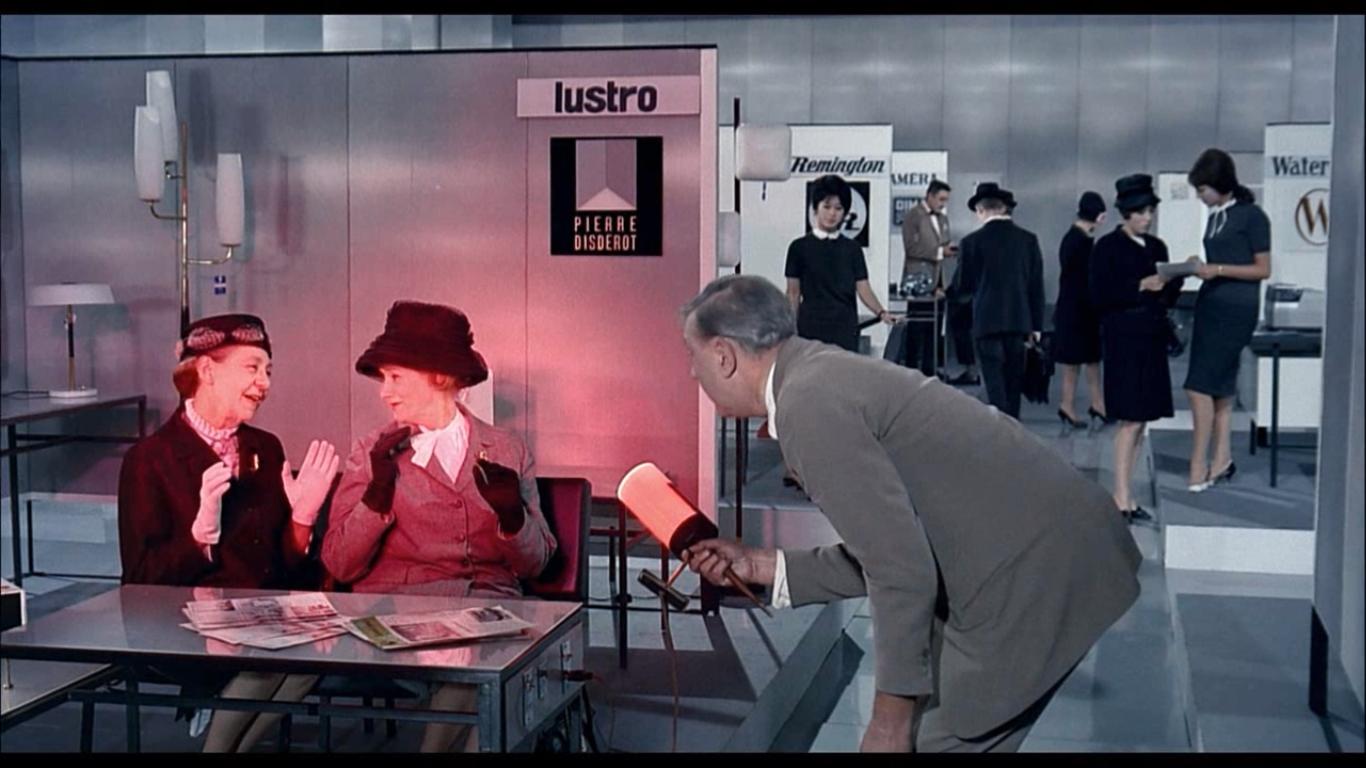

When Playtime unleashes its unabashed and unforgiving modernity on our poor hero, the pinnacle of the conflict is fully realized – as is Tati’s full powers as a master filmmaker. Riding on the massive critical and financial success of Mon Oncle, the director leads us to the apparent final triumph of an imposing, abstract physicality into every aspect of environmental interaction.

There is no nearby quaint village or rustic beachside community here. This is literally “Tativille” – the production’s unofficial name for the massive outdoor sets representing a modern and overwhelming glass-and-steel world. With the ability to move the buildings of this scale-model mini-city (some up to 3 stories tall!), Tati could position the encroaching modernity to manipulate and discombobulate our beloved protagonist any way he wanted. But it’s not just him this time.

From the start, Hulot is brushed into the background. This was no mistake: the director wanted this film to be about a whole series of background characters. Narrative is more of a casual convection than any sort of crucial focus for the film.

Yes, the audience follows sequences of events, but they are many, they are scattered and they follow not a thread, but present a thematic tapestry. This was frustrating and dismissed as pretention by contemporary viewers. Modern audiences should be more attentive as a rewarding and unique experience awaits.

The Hulot confusion has spread everywhere in Playtime. Everyday inhabitants and tourists in Tativille bounce around a manipulative modern city like so many pinballs, making a pretense of naturalness in a beguiling habitat.

As in Mon Oncle, there are hints that this madcap metropolis has a soul of its own. But more than anything, the imposing modernity has altered human abilities and activities. Signs of organic life become more subtle and less frequent. Even Old Paris can only be found in faint reflections throughout the film (glimpses of icons like the Arc De Triomphe). Humanity’s mad constructions of sterile cities reduces our goings-on to being not much more than mice in a maze.

Tati got this, and he unleashed a whole litter of lab rodents into the experiment. The film is so chock thick with sight gags reinforcing the themes, it’s impossible to talk about all of them in a single . Repeated viewings are absolutely necessary, and watching it on anything other than a large screen results in loss of effect. An economic look at choice scenes and recurring narratives only hint at the immersive quality of the film’s milieu.

If there really is a “story” to follow in Playtime, it’s a short one that actually ends right at the film’s midway point. While focus on Hulot’s presence this time around has been reduced, he still nevertheless owns the lion’s share of the movie’s many vignettes. And he owns the longest one.

Starting early in the film, Hulot is on a quest to fulfill some sort of bureaucratic exchange. We never find out what it is and it doesn’t matter – it’s just one of those “you have to find the right guy to sign the right document” things. This mandate brings him to a huge modern office building, as absolutely cold and sterile as the rest of the city. An accidental game of cat and mouse ensues as once Hulot finds the correct bureaucrat. He follows the official into a literal maze of cubicles.

Easily distracted by buzzing and beeping and beguiling architecture, the two are quickly separated. The tangled hilarity which follows rivals the best orchestrations that Chaplin or Keaton have ever devised. Mistaking an elevator for a wall feature, Hulot gets taken for a ride away from his quarry.

Returning, he sees the cubicle maze from above – a living geometric image that gives away the trap of modernity at a glimpse (one of cinema’s finest frames). Chasing after his man, a spinning receptionist at the center of the maze keeps facing in different directions, disorienting Hulot every time he bumps back into her in the maze.

Finally, a sublime gag playing on deceiving reflections sees the official disappearing into nothingness within the featureless guts of the inorganic construct. But that’s not even the punchline. Later in the film, as a crowd of spectators gather in the street to watch workmen precariously transporting a large piece of plate glass, Hulot and the official bump into each other by chance.

The organic flow of their movements in the street brings them together, and the official processes the document for Hulot on the spot. It’s not even a hilarious moment. Tati is telling us with a wry smile that we humans really are a more natural sort than we know, and we can always find each other in the end.

The sheer volume of vignettes in Playtime would require several pages to catalogue, not only in how they play out, but in how they interact. Even upon multiple viewings, there’s always another reinforcing gag happening that the most devout devotee could miss.

Often, multiple gags are occurring on screen at once, not only keeping repeated viewings fresh, but encouraging different seating positions in the theater each time. It’s all done in a fascinating and invigorating cinematic language, a unique visual lexicon, which achieves a lofty ambition without a hint of pretention, and on a grand scale. But the film’s vague reliance on story should not be mistaken for lack of construct.

As with any other film, there is a climax here. Most of the second half of the film focuses on a hastily built night club, the finishing touches of which are still being polished on opening night. Starting at the front door, the place slowly falls to pieces over an extended set of sequences. Nothing is spared – waiters, floor tiles, paint jobs, and ultimately, the walls and ceilings come crashing down amongst a gaggle of painfully bourgeois partyers.

The string of thematically-linked deconstructive sight gags goes on for over 20 minutes, building up to the final calamity. What does it all mean? That our super-fast, pre-fab, instant-gratification lifestyles are built on some pretty flimsy foundations. It won’t take much to knock them down, just a bunch of organic impulses from a bunch of clueless souls.

An important coda of sorts concludes Hulot’s final major film. The parties are over, the night wanes. Sundry citizens spend a late night in a café as the sun starts to hint at its return and the cacophony of the big city day prepares to resume.

It starts with the quiet of early morning hours as almost a remedy for the mad goings on of a modern waking life. But soon enough, the streets are full of people and cars and more activity than you can shake a stick at. And it is here that an interesting bookend of sorts is placed by our director.

The opening shots of the film focused on fluffy, amorphous clouds, which then are contrasted in a subsequent frame by the rigid hard angles of a glass and steel building. It’s Tati’s strong forward signal that sets the tone of the organic’s clash with the inorganic.

Now, at the end of the film, among the frenetic wave of people coming and going, one of the closing shots sees a small crack in one of those super-slick, monolithic bits of overwhelming infrastructure: a worker digging into the street, dishing out some nice, warm earth from beneath it all. Yes, that organic world is still here, buried and waiting beneath us.

No amount of concrete can separate us from it forever. It’s a casual moment, not emphasized, but rather, breathing organically in the edit, as Tati would communicate it to us. The film then does a comedic encore, a sequence of traffic and pedestrians and workers choregraphed in sight and sound to recall a circus atmosphere.

It’s a gentle wave from the auteur, reminding us that yes, this artificial world we’ve built around ourselves is totally ridiculous and so are we. But it’s OK to laugh because in the recognition of what we’ve become, we can also recall where we came from. Nothing to be sad about here, it really is Playtime, let’s not take this world so dreadfully seriously.

Hulot appears in a subsequent film, Traffic, but it’s a half-hearted effort made when Tati was in dire straits. Where Vacances and Mon Oncle were great hits for the director, the very costly Playtime was not. Funding ran out during production and Tati was forced to put a lean on his home to complete the film. The subsequent poor returns put a financial strain on him from which he never recovered.

Traffic was an attempt to capitalize and found sponsorship as a Dutch made-for-TV movie. Hulot at this point had outlived his purposefulness for Tati and only desperation led him to revive the character, creating a less inspirational work. Hulot’s three major films ensured Jacques Tati’s place in cinematic history, and left an indelible mark in the evolution of visual expression.

Amazingly, he crammed in more filmic richness in the decidedly small volume of output he completed in his life than many more prolific filmmakers offer in dozens of works. Hulot makes another appearance, after a fashion, in Sylvain Chomet’s 2010 animated film, The Illusionist, based on an unproduced Tati screenplay.

While very enjoyable and moving, the film doesn’t attempt to reach Tati’s singular visions. Which is the smart play, of course. We have what we have in Hulot. Tati’s legacy packs a mighty big punch in the small volume of packages he left for us. This may be the last lesson from the organic director.

Don’t rush greatness. Let it grow at its own pace. Having a few great things is more valuable than owning a whole lot of mediocrity. One must wonder if the conclusion of his life was not cosmically linked to what these three great films so graciously showed us.