There are very few actors who can claim to have played Hamlet before thirty, but Ben Whishaw is no ordinary actor. A fine example of a classically trained actor holding Hollywood in the palm of his hands, Whishaw has acted with the greats, yet retains anonymity about him, hidden behind his great characters.

Starting in the theatre, Whishaw came to the forefront in the theatrical adaptation of ´His Dark Materials´ (2003) holding his own with other British theatrical stalwarths Patricia Hodge, Dominic Cooper, Timothy Dalton and John Carlisle.

By 2013, he co-starred in John Logan´s newly written play ´Peter and Alice´with Judi Dench as a co-star- and nobody batted an eye-lid. And much of that has to do with his performance in ´Trevor Nunn´s Hamlet in 2004, one The Telegraph hailed as ´An Unforgettable and Most Loveable Hamlet´. Whishaw´s name has become synonymous with Jonathan Pryce, Simon Russell Beale and Mark Rylance as great modern renditions of the Dane.

Though theatre may be his primary oeuvre, he has translated himself well onto the big screen (something Laurence Olivier himself often struggled to do). And what a translation! How many people have James Bond, Bob Dylan and a possible Freddie Mercury biopic on their C.V.? And the man´s not yet forty!

Although a man who has largely taken secondary roles to leading ones,Whishaw has proven himself alongside cinematic heavies such as Dustin Hoffman, Ralph Fiennes, Helen Mirren and Colin Farrell-never losing himself as a well spoken English man of high character and humanity. Using his stage prowess, he has translated quite nicely to the big screen, a greater achievement than you might think- Sir Laurence Olivier himself often couldn´t!

10. The Zero Theorem (2013, Terry Gilliam)

Overshadowed by the worthier peaks of ´Brazil´and ´Twelve Monkeys´, ´Theorem´ is still a fine example of Gilliam sci-fi extravaganza, one that features some of the finest pieces of dialogue heard in a Gilliam film since ´Brazil´ (un-coincidentally, they share the same co-writer Charles McKeown). Ben Whishaw´s part is small, but memorable, his theatrical background to the forefront here, he could well be reciting Tom Stoppard or Peter Shaffer, if not for the sci-fi paraphanelia.

As Christoph Waltz´s character shirks to a variety of examinations, Whishaw enters as the suspiciously titled ´Doctor 3´, the third doctor investigating their malaised client. Refuting his clients incessant us of ´we´with the barb ´there´s only one of you´, Whishaw plays it straight, allowing a darkly comic tinge to enter the proceedings.

Hiding behind a twirly, combed fringe, Whishaw´s uber-bohemian look adds to the film´s dystopia. Stately thin, his iteration that “You’re not dying. Although, in a way,from the moment of birth,we all begin to die. Call it divinelyplanned obsolescence.” is said so plaintively and matter of factly, it´s somewhat scary. Impressive for such a passive performance to be so emotive.

9. Skyfall (2012, Sam Mendes)

The James Bond International Fan Club publicly cried after Desmond Llewelyn´s death. For over thirty years, he had graced the Bond films with his effervescent presence as Q. Starting off as the authority figure to Sean Connery´s effortless, rebellious cool, by the nineteen eighties he became an invaluable companion to Roger Moore and Timothy Dalton.

A side appearance with Pierce Brosnan was beautifully sent off in ´The World Is Not Enough´with promises of Q´s retirement, this scene was made all the more poignant by Llewelyn´s death post filming. Seemingly irreplaceable, John Cleese´s attempt at the character turned witty into pathetic, the boffin the punchline to his own jokes, and Q disappeared from cinema screens for ten years.

Thankfully, 2012´s ´Skyfall´ based its entire script about old versus new ideas, a gun toting Bond fighting a technological wizard, the question of espionage a thing of the past and future. Taking the inspired method to subvert the idea of Q (before an older man chastising a younger Bond, replaced by a caustic Bond cynical of this young boffin), Wishaw was cast as a youthful technophile, as quick at pressing buttons as Bond is at shooting.

“Well, I’ll hazard I can do more damage on my laptop, sitting in my pyjamas before my first cup of Earl Grey than you can do in a year in the field ” he deadpans in a beautiful scene set admiring a beloved Turner. Reuniting with former Layer Cake co-star Daniel Craig, Whishaw is less obviously patronising than his predecessors, but bites with the sanguine (and funniest laugh in the film) “Were you expecting an exploding pen? We don’t really go for those anymore!”. Pointed.

Based on this performance (and a reprisal in ´Spectre´), Whishaw is welcome to the part for the next decade or so. If Llewellyn remains the indelible ´Q´, then Whishaw is a worthy and reverent re-invention. And should Craig choose to vacate Bond 25, Whishaw needs to whip the next agent into shape!

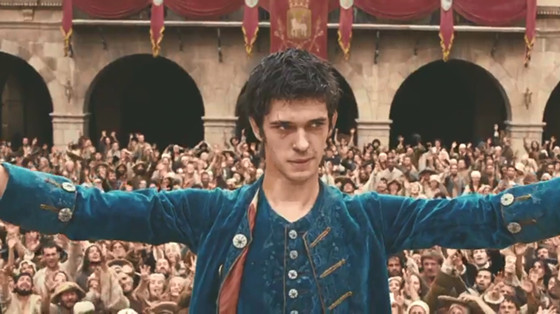

8. The Tempest (2010, Julie Taymor)

It´s doubtful if Julie Taymor will ever make a good film. Much like Zack Snyder, her films follow shot after luminuous shot with a horde of neon colours thrown at its viewer, but it comes at the cost of the story. Even the reliable bard´s narratives are hidden by a florry of grandiose lighting. But The Tempest features strong performances from its lead actors; Helen Mirren her strong self, Felicity Jones´ Miranda a taste of better performances to come and Whishaw´s temptuos Ariel the anchor to the flick.

“I love [Whishaw], “Taymortold Manhattan Movie Magazine “and I thought he and Helen would have this chemistry, not necessarily sexual, but there’s the tendency of the old woman with the young man and having a relationship and it seemed to me it could be very cool. One of the stronger aspects of the film is the chemistry shared between Whishaw and Mirren; his ethereal theatrics a nice comparison to her more subdued performance.

One of Whishaw´s more physical roles, he spends much of the film bare chested and silhouetting in a starlit sky among neon shots of differing colours, throwing himself around the camera´s moving eye with ace, grace and speed.

Cherub like in appearance, Whishaw does what few actors get to do onscreen: play a part, expressing his movements with long swishes of his arms, rather than internalising a minor gesture for the viewer to pick up on. It brings his theatrical background very much to the fore, even if the film as a whole may be his residual bête noire.

7. Brideshead Revisited (2008, Julian Jarrold)

Talking to Collider, Matthew Goode claimed he was trepidatious about working with Whishaw; “I was slightly daunted by working with Ben as he’s given the best performance of Hamlet in 40 years, so suddenly he’s opposite me”.

Approaching their different parts and characteristics, Goode and Whishaw met to talk ” through all the thematics in this is hugely important and chatting also about the relationship that Ben and I wanted to have as far as our characters and where that was going to be set.” Where Goode´s Charles Ryder romanticises with dreams of art, Whishaw’s Lord Sebastian Flyte imagines his as one great painting. Two devastatingly handsome men, Goode and Whishaw bring a decadent seductiveness to the proceedings.

Whishaw’s flamboyance is proven more fitting by his growing dependency on alcohol, hidden behind an enebriated mask; he loves the decadence, and the liquid supplies are on of its assets. An immature boy brought up by affluence, Flyte knows little else of life outside of hedonism.

Tempting his new found friend to the finer delicacies of life, he offers a tantalising offer of “a basket of strawberries and a bottle of Chateau Peyraguey, which isn’t a wine you’ve ever tasted so don’t pretend.” Whishaw’s no stranger to the sadder facets of his character, Flyte’ s possible homosexual tendencies quashed by Ryder’s differing interests, made pointed by Whishaw’s exasperated “I asked too much of you. I knew it all along, really. Only God can give you that sort of love. “

The film as a whole isn’t as nuanced as the excellent 1981 television series, though Goode and Whishaw are worthy successors to Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews; in Whishaw’s case, he is very much as natty and hoggish as Andrews, though Whishaw’s twenty something veneer makes him a more realistic immature patrician than the thirty-three-year old Andrews. And as fops go, its up there with Daniel Day-Lewis’s tragic Cecil Vyse in ‘ A Room With A View’ (1985).

6. Bright Star (2009, Jane Campion)

“To me, it seems incredible that he managed to get up every day and carry on.” Whishaw told The Telegraph. “But Keats encountered death a lot in his life. Most of his relatives died. And I think that gives you a different perspective on what things mean. As well as sensitivity, he had real single-mindedness and resilience.”

Playing one of the greater Romantic poets (less obviously hedonistic than Lord Byron, more accessible than Percy Shelley, Keats still remains a man of written excellence), Whishaw´s devoted state to Fanny Brawne is as captivating as that of Heathcliff´s to his fair Catherine Earnshaw.

As befitting a man with lexical prowess, Whishaw utters his thoughts on love with delicacy, and a fearful, feyful, timidity:”I had such a dream last night. I was floating above the trees with my lips connected to those of a beautiful figure, for what seemed like an age. Flowery treetops sprung up beneath us and we rested on them with the lightness of a cloud.” Loquacious it may be, Whishaw shows the poets fear for romantic emotion by avoiding to answer Brawne´s question as to whether the lips in his dream were hers.

Whishaw´s remarkably youthful face (though twenty nine at filming, Whishaw looks young enough to portray the poet, twenty five years young on his death bed) brings bouyancy and tenacity to the part, poetic to the masses, inward to his emotions. Whishaw brings texture to Keats´ verbosity.