5. High Fidelity (2000)

Cusack re-teamed with his Grifters director Stephen Frears (not to mention two of his Grosee Pointe Blank cowriters D.V. DeVincentis and Steve Pink) for High Fidelity. In the film, Cusack plays a fairly typical Nick Hornby (who wrote the source novel) protagonist: he is an overgrown man-child lacking the emotional maturity to fully commit to another human being.

Typically dry but always compulsively watchable, Cusack’s work in High Fidelity creates a hilarious, infuriating, and messy depiction of a very loveable loser. The greatest feat of his work in the film, however, is reliant upon how well Cusack is able to, in spite of how flawed the character is, make everything relatable and human.

He’s as funny as he is painful to watch because his character’s selfishness and lack of awareness always come from a place that is identifiable to our most flawed and buried emotions… Which also happen to be some of our most honest ones.

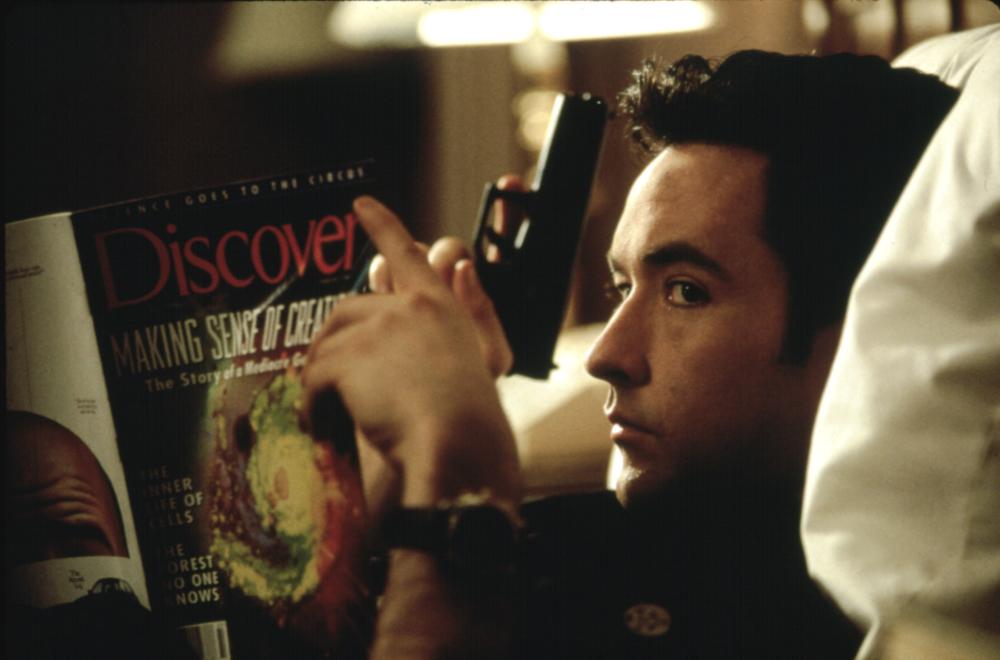

4. Grosse Pointe Blank (1997)

Cusack had a very large creative hand in Grosse Pointe Blank. He co-wrote the screenplay, served as a co-producer, and stars as Martin Blank, an emotionally cut-off but-still-fairly-decent guy who also happens to be a hit man.

When his next assignment falls in the town he grew up in and on the anniversary of his ten-year high school reunion, Cusack’s character revisits old teachers, friends, girlfriends, and demons with the resulting arc of (re)discovering his humanity.

Grosse Pointe Blank is an interesting film with a number of risky tonal shifts that ultimately pay off. It’s, at heart, a comedy, but it’s also a very smart and unique one. It makes fun of the “cool” violence that was being created by Quentin Tarantino and his many knock-offs at the time while also taking stabs at corporate America and business ethics.

It ultimately finds its way to a very satisfying and profound mediation on accepting personal responsibility for one’s actions. It’s soundtrack also happens to be one of the best eighties music compilations ever assembled.

Cusack’s performance in Grosse Pointe Blank is a classic one in his arsenal. It combines the invisibly brilliant comedic timing found in his early work with the emotional depth and experience provided by his more mature choices later on in his career. He’s perfect as a killer as cold as Martin Blank, but he can still somehow manage to charm his way out of being anything less than loveable onscreen.

3. Say Anything (1989)

Speaking of loveable and John Cusack roles, it doesn’t get much more of one or the other than Say Anything. An homage to Cusack’s depiction of Llyod Dobler will most likely be what winds up on his tombstone one day, and justifiably so.

Dobler was Cusack’s last hurrah as a teenage character in a teenage film (Dobler is nineteen) and it was a great note to go out on while also being a simultaneous shift to more adult works. His portrayal of Dobler is complex, layered, imperfect, and neurotic while still managing to be wholly affable.

Written and directed by Cameron Crowe, who can often be found guilty of laying on the saccharine far too heavily, Say Anything greatly benefits from Cusack’s presence because Dobler, while wonderfully written, could have easily been played as vanilla and simple.

With Cusack’s extraordinarily sparse use of his smile and his constant deadpan gaze peering out through his saggy eyelids, he gives Dobler a history and a weight lesser actors (and even many good ones) wouldn’t have been able to provide.

In Say Anything, Cusack counter-balances an extraordinarily sweet story with the presence of an intelligent and complicated soul. It’s one of the most human portrayals of a teenager in love ever put on film, and Cusack manages such realism while still successfully portraying a character that is hopelessly optimistic and (knowingly) naively romantic. A character’s passion has rarely been portrayed so quietly, and yet so strongly, onscreen before or since.

2. Being John Malkovich (1999)

Spike Jones’ directorial debut, Being John Malkovich, is also Charlie Kaufman’s first-produced and hilariously mind-bending screenplay. In addition, it also features, to date, the best example of what John Cusack can do when he sheds his habits, charms, and everything else that makes him John Cusack.

In Being John Malkovich, Cusack takes on the first of what would later become a fairly standard set of traits that the male leads in most of Kaufman’s works would later share: high levels of incurable neuroses, the tendency to pine over only the most unrequited love interests, introversion, and a propensity towards wallowing in self-induced misery.

Cusack is as unlikable as he’s ever been playing the sexually unappealing puppeteer who discovers a gateway into the actor John Malkovich’s head. He’s needy, nerdish, and utterly despicable to his sweet and unconfident wife (a career-best performance from Cameron Diaz).

Cusack’s obsessive, and eventually deranged, portrayal of a Kaufman protagonist is one of the biggest risks of his career, and the pay off is as good as it’s ever been. The result is a standalone and classic effort in Cusack’s large and diverse body of work.

1. The Grifters (1990)

Director Stephen Frears’ adaptation of Jim Thompson’s hard-boiled noir novel is easily the darkest film on this list and of Cusack’s career. The Grifters, set in 1990’s Los Angeles, also happens to be the best.

Playing a small-time conman who is in the middle of the oddest of love triangles with his big-time con-artist mother and his highly vindictive and dangerous con artist girlfriend, John Cusack delivers his most interesting, thought-through, and internally conflicted performance to date.

Roy, Cusack’s character in the film, is a lost soul. He’s too tainted by the lifestyle his mother (a great and ultimately terrifying Angelica Houston) raised him in, yet he’s doesn’t have the street smarts or toughness it takes to survive it on his own.

He’s desperately trying to belong somewhere, with someone, but also manages to unwittingly put himself in the worst and most vulnerable position with the most destructive woman (an equally great performance by Annette Bening) he can find. In short, he’s the worst kind of momma’s boy: completely unaware and completely in denial of his true motivations.

Cusack goes to some pretty sick places with his performance in The Grifters. His interpretation of Roy, however, keeps from him wearing any of it on his sleeve.

Cusack uses his looks, confidence, and charisma to create a character who exhibits arrogance to mask extreme, and deeply hidden, insecurities, pains, and desires. He is compulsively drawn to both Bening’s and Huston’s characters, but is unable to objectively understand (or perhaps, more accurately, admit) as to why.

Cusack, once again, fills his role with subtlety and restraint. His character’s psychological issues aren’t fuel for melodrama or an exhibition of high emotions. They’re on his stoic face, in his saddened eyes, and so small that you might miss them if you blink. They are wholly present, however, and you somehow feel them with him (if you dare to go there…) when watching the film because of the inherent truthfulness with which they’re acted.

In The Grifters, Cusack delivers a performance that is essentially the best of both worlds: he uses a familiar toolbox to create a character that is unlike anything he has played before or since.

As disturbing and uncomfortable as the film gets, Cusack always stays grounded in reality, and it’s not too hard to see that his character is heavily suffering behind that sarcastic smirk. Most actors don’t have the humility or maturity to tackle such a meaty role in such a non-flashy way.

With anyone else, a similar interpretation could have easily been flat and uninteresting. But in the case of The Grifters’ Roy, the boy who loved his mother far more than he ever should have, it works brilliantly because, quite simply, he’s portrayed by John Cusack.

Author Bio: Matt Hendricks is an independent filmmaker with several projects currently in development.