5. The Witch (Robert Eggers, 2015)

Some people see religion as a form of mass hysteria, some people are more forgiving, some people are believers. But a constant characteristic of the Christian faith, especially a radical faith like the Puritan current that was popular in the Seventeenth century, is the omnipresence and constant menace of sin inhabiting nature.

The falling apart of the family in the film could be attributed to actual demonic presences – witches or the influxes of Satan on their life – or it could be caused by their obsession to their religion. There’s even the suggestion that the main cause could be the fact that the crops are failing because of a fungus that is releasing some hallucinogenic substances.

From the first scenes, where the mother sings a religious chant with a haunting voice while a violin plays frighteningly and the sun goes down behind a monolithic dark forest, madness descends on the characters.

Everyone gets progressively unstable, from the first half of the film when the viewer looks through a natural eye (or at least we think so) to the second half in which the perspective shifts and everything is witnessed through the eyes of the crazy family members.

The frames get smaller, the close ups more insistent, the editing quicker, the scenes darker, some moments are more visually adventurous, impetuous, the walls of reality are being broken, everything is made possible by hysteria. The end scene, with the fire, the nakedness, the screaming, is the apex of this madness.

In the film, religion is associated with God and order, witchcraft with chaos and Satan, and it is clear that in this case the madness is seen as the destruction of man, the crumbling of the mind to fanatical beliefs, and endless guilt and grief.

The witch, the woman, the body, sin, chaos, flames, animals and the forest are all part of the same insanity, to the eye of a traditional patriarch, a traditional Christian, a person who believes in a transcendent order and a firm moral code.

This conviction is soon shattered and cedes to the unstoppably chaotic freedom that coincides with damnation, and if at first the madness is only perceivable as a whisper in the wind, a ghost hiding in the atmosphere, it all mounts to a dynamic conclusion where Chaos reigns under a pagan moon.

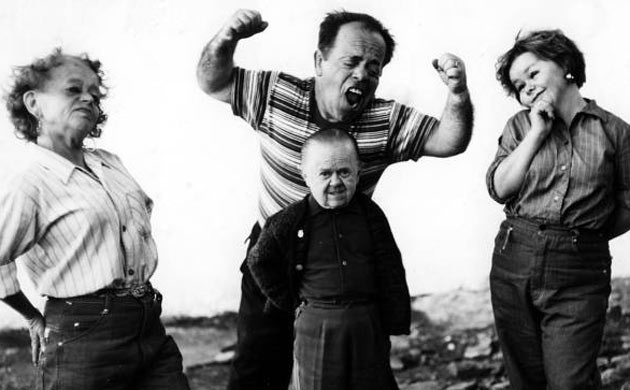

4. Even Dwarfs Started Small (Werner Herzog, 1970)

Herzog’s film is heavily influenced by two great films – “Freaks”directed by Tod Browning, and “Zero de Conduite” directed by Jean Vigo. In these films, as is the case in Herzog’s film, violence, madness, mayhem are creative, They are deliberate and gleeful acts of resistance against a system that is perceived as humorless and limiting, stagnating and saddening.

Laughter is an element extremely present in the film, as a sign of madness but also a sign of derision towards the law, towards mute acceptance of the order.

In Herzog’s films we are always left wondering whether the madness we see on screen is the effect of an actual instability of some particular characters or just the natural consequence of the contrast of two different perspectives. Or maybe we can accept that we are all mad, the universe is mad and we should observe it with a sense of collective hallucination.

3. Suicide Club (Sion Sono, 2000)

Perhaps no film has the sense of apocalyptic doom, of disturbing atmosphere, of hysterical madness reinforced by postmodern and cyberpunk paranoia, like Suicide Club.

In the film, even an innocuous J-pop song becomes the symbol of an insanity in Japanese society that creates an epidemic of suicide. The first scene, with the collective suicide of a huge number of girls who happily jump under a moving train, is one of the scariest visualizations of irrational behavior and a deeply insane will to die in cinematic history.

The sense of dread that the film has, as it descends into the seedy underground of Japan, through dark nights, rain, and unstable and surrealistic characters, gives the image of a society that is comparable to an asylum, inevitably speeding towards its destruction, unable to distinguish a crazy person from a sane person, unable to hold onto life and keep the natural order flowing.

Technology, capitalism and general dehumanization brought Japan towards the precipice, and now madness rules, and it is not subversive, it is not creative, it is not socially aware, it is the manifestation of the shared Kamikaze instincts of the species and the devious path that human beings are following, a path that leads into a black hole, smiling and holding hands while enjoying our appetite for self-destruction.

2. Mother Joan of the Angels (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1961)

Few films present the conflict between madness and order, disruptive instinct and dogma, quite like this Polish film. Again, the madness of the nuns (the film is based on a real story) seems to be caused by the repression of their sexuality, and the relationship between the head of the nuns and the priest is central to this thematic element.

The madness is carefully framed and scripted like a dance, or a theatric exercise. The people who represent the order look strangely amorphous, incapable of moving fluidly, while the women feel so free, occupying every edge of the frame, running aimlessly, moving frantically, with rolling, falling, movements that would influence the great Andrej Zulawski and are inspired by the theatre of Grotowski.

The film, a predecessor of the much more famous “The Exorcist”, has a sense of madness so deep that it seems to infest the land as well. Kawalerowicz conjures a catastrophic view of a godless, mad world.

1. The Exterminating Angel (Luis Bunuel, 1962)

We are all animals. That is Bunuel’s thesis, and the middle and higher classes, with their welcoming façade, hold an ever deeper sentiment of collective hysteria, tendency to panic and irrationality. Starting from a premise that nods to his surrealist beginnings,

Bunuel constructs a film that develops itself on a fully metaphorical level. Where the people, invited to a formal dinner, find out, not by physical inspection, but by some sort of instinctual recognition, that they cannot leave the place.

This absurd claim is mutely accepted by all the people, and panic, chaos and madness will rapidly become the main qualities of the elite, who so carefully try to hide it behind a cultural and ideological shield.

Although the film never descends into complete hysteria until the final sequences, the rupture of the barrier of cordiality and formality fueled by a progressive sense of entropy and claustrophobia brings the guests (and subsequently the churchgoers) closer to their real, brutal, selfish, bestial nature. They are undoubtedly crazy, but it is arguable that their surface, their passive belief into a set of rules that they themselves have established, is the real madness.

The film keeps its sense of spiraling chaos, of manic violence ready to erupt, of things crumbling, of morals shattering, and penetrates the monstrous reality behind the mask of the current Spanish society.

Author Bio: Gabriele is an Italian film student studying in Scotland. He is an experimental and arthouse cinema enthusiasta and a believer in the crucial importance of freedom of artistic expression.