5. The Player (Robert Altman, 1992)

Opening with a tracking shot that knowingly references other, more iconic tracking shots, The Player is one of the most dense meta-movies that now deserves to be considered as a masterpiece in its own right.

Whether its The Long Goodbye or McCabe and Mrs Miller, Robert Altman has always demonstrated his incomparable way of taking a genre people think they understand and imbuing it with his own independent spirit, replete with overlapping dialogue, moral ambiguity and ensemble casts. In this case he takes the metafilm and reveals the rotten underbelly that could be found in Hollywood by the start of the 90s.

It stars Tim Robbins in a career best role as an unrelenting Hollywood executive, who has the enviable position of choosing whether or not to green-light scripts depending on the shortest of pitches. Soon his reputation proceeds him, and he starts receiving ominous death threats in the form of postcards from someone he may have scorned in the past.

How he deals with the problems attendant upon him shows the moral shortsightedness of the industry after the me-first culture that had sprung up in the previous decade. Ostracised by Hollywood in the 80s for not fitting with the new standard of commercial considerations, The Player can be seen as Altman’s witty and sardonic revenge, taking potshots at nearly everyone in what can be considered as the most narcissistic business of them all.

4. Contempt (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963)

American cynicism meets French Arthouse in Contempt, Jean-Luc Godard’s first and only attempt at a studio movie that saw him turn the camera inwards to an industry he was still getting to grips with. The result is a lament for a culture Godard thought was becoming cheap, filtering it through a brief moment of infidelity that creates an irredeemable rupture in a couple’s marriage, in the process creating a highly self-reflexive work that can be seen as modernist cinema’s aesthetic highpoint.

It tells the story of a French screenwriter (Michel Piccoli), who in adapting The Odyssey for a large American production, finds that the story of Ulysses and Penelope may just be describing him and his wife Camille — played of course, by the inimitable Bridget Bardot. In a famous argument with the studio, which wanted Bardot to be nude at least once, Godard decided to show her naked body right in the first scene, before going on to make a different movie entirely.

Nevertheless, Bardot isn’t the best casting choice in this film about films. In adapting a story of an exile, the director in Contempt is played by none other than exile from the Nazis and godfather of German cinema, Fritz Lang. When referring to the cinemascope format the very same film is in, he famously utters: “Oh, it wasn’t meant for human beings. Just for snakes – and funerals”. The rest of the film is as humorously sardonic, tugging between an enjoyment of cinemas pleasures and indicting its commercial considerations.

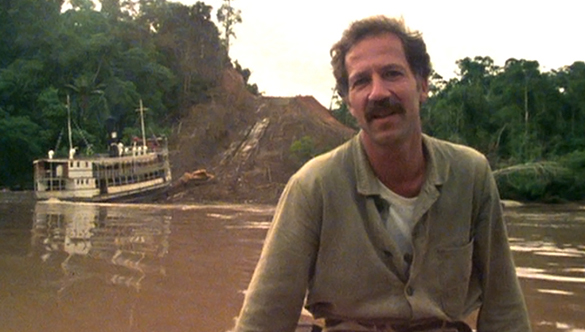

3. Burden Of Dreams (Werner Herzog, 1982)

The greatest making-of documentary of all time, Les Blank’s Burden Of Dreams depicts one man’s extraordinary struggle to execute his unique cinematic vision. That man, of course, was Werner Herzog, who valued authenticity in film above all else, taking his entire cast and crew to the Peruvian jungle in order to shoot his masterpiece Fitzcarraldo.

In telling the story of a man who takes an entire steamship over a hill in order to access a rich territory, Herzog wanted to make it happen for real, in the process hiring hundreds of local villagers to enact that daring feat; made all the more amazing by the fact that it had never actually been done before.

For his efforts Herzog dubbed himself the “Conquistador of the useless”. Yet this wasn’t the production’s only struggle, also running into immense trouble with the Aguaruna people, against whom Herzog hired a local militia Army to defend himself. What is heavily ironic, when watching Burden Of Dreams, is seeing how, in depicting the rubber baron John Fitzgerald, Herzog shares many of the same dictatorial, highly driven qualities.

Before he became better known as the Bavarian documentarian with that unmistakable voice, Burden Of Dreams also shows that Herzog was, and still is, a visionary director who goes further than any other in order to realise his ambitions. The result is a fierce statement to show why a filmmaker should never give up on their dreams.

2. 8 ½ (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Constantly bookmarked as one of the greatest films of all time, 8 ½ sees Italian maestro Federico Fellini firing on all cylinders in his paean to both movie-making and his own narcissism. Named 8 ½ because it was literally his eight and a half movie (you get the half from the two features and a collaborative effort), it tells the story of a famed director (Marcello Mastroianni) who cannot quite get over his writers block.

By not being able to move forward, the story instead uses his darting mind and imagination as a type of narrative device, becoming a freewheeling exploration of what goes on in the mind of the world’s greatest movie director. The result is simply mesmerising.

Baffling viewers upon release, and considered to be Fellini running out of ideas — after all, the film was about a director who had no ideas for his next film – 8 ½ actually sees the Italian auteur at his highest capacity for invention, running the creative process through the whole gamut of Freudian, Christian and otherworldy imagery, yet never tethering it to any one fixed meaning.

It is through this boundless capacity that Fellini argues how, despite all writing and directing having some basis in autobiographical truth, film is the ultimate artistic medium when wanting to let your mind run free.

1. Day For Night (Francois Truffaut, 1973)

Francois Truffaut’s Day For Night is in many ways the quintessential ‘movie about movies’ due to the way it portrays nearly every part of the filmmaking process; whether that’s making a daytime scene look like night, creating snow, or training a cat to behave.

It reveals that filmmaking works just like any other business, and can be just full of compromises and shattered dreams as grandiose ideas and schemes. Truffaut plays an alter-ego version of himself, directing a French melodrama named Je Vous Présente Paméla, and managing between his original Citizen Kane-inspired desires and the technical realities of being on set.

A marvellously-paced ensemble drama including Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Aumont and Jean-Pierre Leaud, the film balances a variety of different stories that demonstrate the strange temporal nature of a film set, in which romances can be accelerated and intense rivalries can be made, only for the whole thing to dissolve by the end of the final wrap party. Close to all nuances of human life can be found within the confines of this movie.

What makes it so affecting is that the film-within-the-film is not supposed to be particularly good, yet shows that for some people, the greatest pleasure can be found simply by getting on with their next project. For a man who started off as a film critic, Day For Night ends up being Truffaut’s greatest love letter to a medium he had been wrestling with his entire life.

Author Bio: Redmond Bacon is a professional film writer and amateur musician from London. Currently based in Berlin (Brexit), most of his waking hours are spent around either watching, discussing, or thinking about movies. Sometimes he reads a book.