The history of film can’t go forward without having looking at the past. Understanding a way a great director made a masterwork can give a small insight to their mind, and can help us to unveil the mystery of a film.

Documenting a filmmaker gives a way of making history through their medium, and gives a fresh look at their work. In these 10 recent examples, we can find old masters (Welles, Hitchcock and Fellini), active and important filmmakers (Allen and Takahata), failed dreams (Jodorowsky) and film-therapy (Kim Ki-Duk). All these portraits provide a new tool to understand a little bit more about cinema itself.

10. Arirang (Kim Ki-Duk, 2011)

The only film on the list where the director is also the subject matter of the film. After a shooting accident where an actress was almost killed, Kim Ki-Duk has his biggest artistic crisis ever.

Feeling conflicted with cinematography, he wasn’t capable of shooting for years, and “Arirang” was his way to find a reconciliation with film. But like his films, this process is extremely tormented and violent.

“Arirang” has been a film that is too personal and extreme for a big part of the audience, and it wasn’t well received. It is hardly an enjoyable film, showing Ki-Duk shouting in front of the camera and doing self-interviews that makes us doubt his mental faculties.

The resolution isn’t clear, and he doesn’t seem to be very interested in finding a cure or a narrative for his film. Instead we have a film diary that is scary and difficult to penetrate, but one that definitely belongs to one of the most original and extreme viewing experiences of the last years.

Kim Ki-Duk returned to cinematography, and his films look more disturbed and aggressive than ever, experimenting with cheap digital cameras and different sexual deviations, Kim Ki-Duk is a filmmaker of the extreme, and this might be his most extreme film ever made.

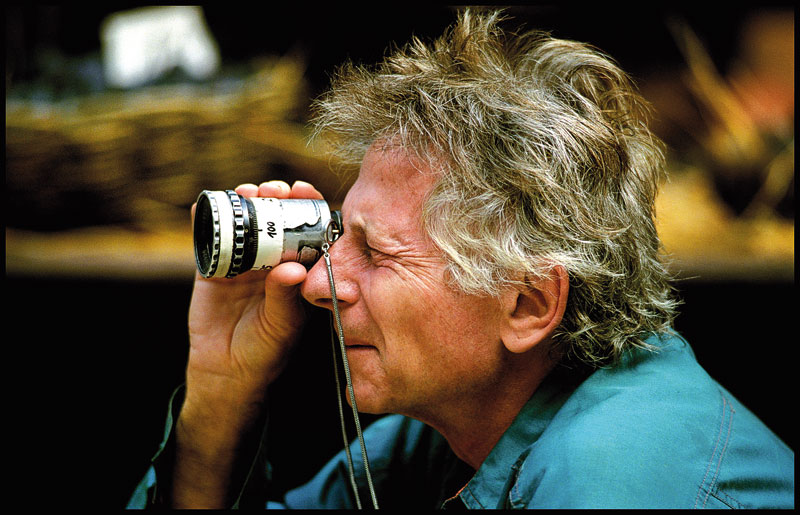

9. Roman Polanski: A Film Memoir (Laurent Bouzereau, 2011)

“A Film Memoir” is structured as a long conversation between two longtime friends, Roman Polanski and his life-collaborator Laurent Bouzereau. In the middle of one of his many turbulent life moments, the conversation is held in Polanski’s residence in Switzerland while he waits for the verdict of his lawsuit.

Not too revolting in that aspect, as there are already three different documentaries on the theme, the film uses his house arrest as an excuse to make a review of his life as a film memoir.

Polanski gives a big space to tell about his two biggest and troubled episodes: his repressed childhood in Nazi-occupied Poland, and the assassination of his wife Sharon Tate.

And even if the two episodes had a strong coverage (his childhood inspiring many scenes for “The Pianist” and Sharon Tate’s case in the press), it is the first time we can hear it directly from Polanski’s mouth, and it is very clear how these episodes tremendously affected his life and films. But he talks also about his beginnings in film school, and his feelings toward his most important films.

The film gives good coverage of a filmmaker who had been famous for his remarkable films in the same way he is recognized for his law problems and personal tragedies.

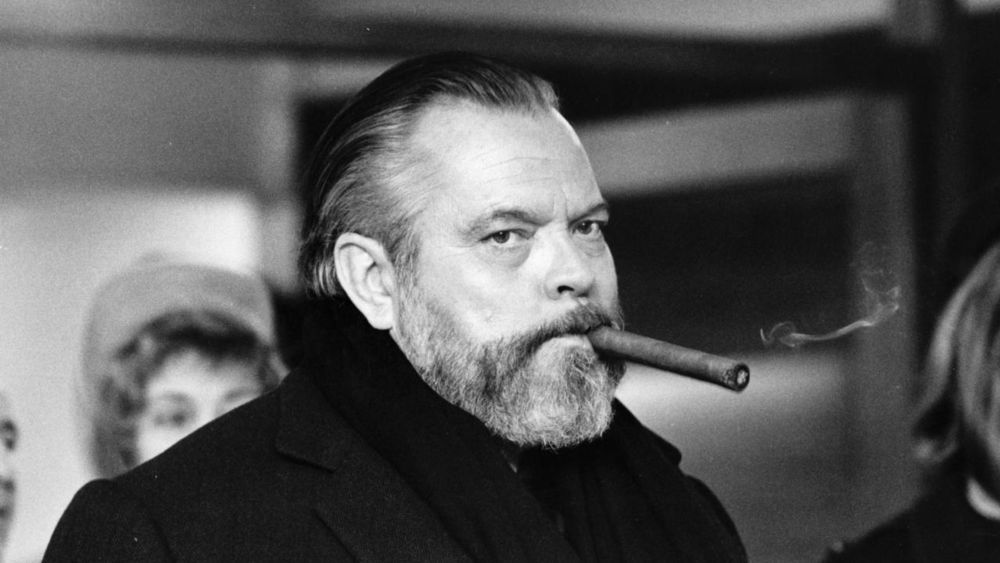

8. Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles (Chuck Workman, 2014)

Orson Welles must be the most famous filmmaker with so many unknown aspects of his life and work, with two of the most remembered and important films ever, “Citizen Kane” and “Touch of Evil”, overshadowing his less successful work, and leaving a good amount of unreleased material. His eternal problems with Hollywood are shown, and how nobody wanted to give him a job after making of of the most important films in history.

Welles is shown as a man obsessed with his work, and who believed any piece of pure art needed time and resources to develop. In a classical chronological way, the film makes a biography concentrating on his films.

Through five different chapters organizing different periods of his life, the documentary shows Welles’ films and different media references to him. From “The Simpsons” to Richard Linklater’s “Me and Orson Welles”, Workman’s documentary does a great job compiling footage probing into how profound was Welles’ influence on popular culture.

The film also remarks on the different ways that Welles worked outside studios and without a normal Hollywood budget. Calling him an indie-pioneer, the film shows how Orson Welles was one of the first filmmakers making ambitious films without any financial support.

7. Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel (Alex Stapleton (2011)

In a place where filming is impossible to separate from money-founding, Roger Corman’s approach opened a new way to see things in Hollywood. Corman can be seen as the first truly spirited indie filmmaker, and as the mentor of a new way of work. Coppola, Scorsese and Nicholson owe him their first steps into the business, and showed them what it was all about.

Even if the core work of Corman is related with not well-respected films, it is impossible not to have respect for him after watching Stapleton’s documentary. The age of the collaborators probes into how much influence Corman had, and still has.

A journey through his first Poe adaptations until his influence on modern horror and action, it seems that Corman is one of the most underrated influences in Hollywood. Corman was respected in the art house world, and at the same time was one the most important guys behind their distribution.

Corman was showing Bergman and Kurosawa to Hollywood filmmakers, again changing the industry, and influencing the young minds of New American cinema.

6. Altman (Ron Mann, 2014)

Going around the “Altmanesque” concept, different actors and directors discuss the meaning of the word. But if “Felliniesque” is a term used to describe certain aesthetic forms, most of the definitions of “Altmanesque” given in the documentary are about an attitude.

“Altmanesque” is being confident and fearless about your steps, or spitting in Hollywood’s face, or never giving up a good idea. Robert Altman was all this and more, and in Ron Mann’s documentary we can get an inside look to his private life and what defined his work as a director.

The documentary builds a narrative consisting of several of Altman’s interviews depicting his life and his relationship with film. The rest of the narrative is given by his all-time collaborative crew and his wife. Making a trip around his most important films, including the smashing success of “MASH” (1970) and the stressing failure of “Popeye” (1970), the private life of Bob Altman is impossible to separate from his life as director.

To see how Altman died making films because he couldn’t stop, because he never wanted to not be filming, is a beautiful and moving event. It’s recommended to any Altman fan, but also to anyone who loves films above all.